Astronomica (Manilius)

Upon its rediscovery, the Astronomica was read, commented upon, and edited by a number of scholars, most notably Joseph Justus Scaliger, Richard Bentley, and A. E. Housman.

The only historical event to which there is a clear reference is the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest—a decisive loss for Rome that forced the empire to withdraw from Magna Germania—in AD 9.

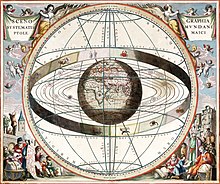

[24][31] In this section, the poet spends considerable time contemplating the Milky Way band,[24][32] which, after exploring several hypotheses as to its existence,[nb 5] he concludes is likely to be the celestial abode for dead heroes.

According to Manilius, "Every path that leads to Helicon has been trodden" (omnis ad accessus Heliconos semita trita est; all other topics have been covered) and he must find "untouched meadows and water" (integra ... prata ... undamque) for his poetry: astrology.

[39][40] Manilius ends the book's preface by saying "that the divine cosmos is voluntarily revealing itself both to mankind as a whole and to the poet in particular", and that he is set apart from the crowd because his poetic mission has been sanctioned by fate.

Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces),[43][46] before discussing the aspects and relationships between the signs and other objects.

[d][55][56] The third book – which focuses mainly on "determin[ing] the degree of the ecliptic which is rising about the horizon at the moment" of a person's birth – opens with Manilius's reiteration that his work is original.

[57] Most scholars consider the third book to be highly technical; according to Goold it "is the least poetical of the five, exemplifying for the most part Manilius's skill in rendering numbers and arithmetical calculations in hexameters".

[57] A similar but less favorable sentiment is expressed by Green, who writes that in this book, "the disjuncture between instruction and medium is most obviously felt [because] complex mathematical calculations are confined to hexameter and obscured behind poetic periphrasis".

[m][77][78] The book is punctuated at lines 4.387–407 and 4.866–935 by "exhortation[s] of the frustrated student", where complaints that astrology is difficult and nature is hidden are countered by statements that "the object of study is nothing less than (union with) god" and "the universe (microcosm) wishes to reveal itself to man".

[81][80] According to Green, the digression, which is by far the longest in the poem, "is very well chosen, in as much as no other mythological episode involves so many future constellations interacting at the same time; Andromeda (e.g. 5.544), Perseus (e.g. 5.67), the Sea Monster – strictly, Cetus (cf.

[81] Conversely, Housman compared it unfavorably to Ovid's version of the story and called Manilius's retelling "a sewn-on patch of far from the best purple" (purpurae non sane splendidissimae adsutus pannus).

[82] A similar sentiment was expressed by the Cambridge classicist Arthur Woollgar Verrall, who wrote that while the episode was meant to be a "show piece", it comes across as "a poor mixture of childish rhetoric and utter commonplace".

[87][89] Concerning this vacillation, Volk writes; "It is clear that there is a certain elasticity to Manilius' concept of the divinity of the universe ... Is the world simply ruled by a diuinum numen (cf.

[91] According to Volk, this interpretation of the universe, which states that it has a sense of intellect and that it operates in an orderly way, thus allows Manilius to contend both that there is an unbroken chain of cause and effect affecting everything within the cosmos and that fate rules all.

[92] Volk points out the poem borrows or alludes to a number of philosophical traditions, including Hermeticism, Platonism, and Pythagoreanism[93] but the prevailing belief of commentators is that Manilius espouses a Stoic worldview in the Astronomica.

[5] Scaliger and Bentley praised Manilius's handling of numbers in verse,[110] and the Harvard University Press later echoed this commendation, writing that he "exhibit[s] great virtuosity in rendering mathematical tables and diagrams in verse form",[5] and that the poet "writes with some passion about his Stoic beliefs and shows much wit and humour in his character sketches of persons born under particular stars".

According to Green, it is "riddled with confusion and contradiction"; he cites its "presentation of incompatible systems of astrological calculation, information overload, deferral of meaning and contradictory instruction".

[19] According to Housman, based strictly on the contents of the Astronomica, one cannot cast a full horoscope because necessary information – such as an in-depth survey of the planets and the effects constellations both inside and outside the zodiac produce upon their setting – is missing.

[19] Goold writes that "a didactic poem is seldom an exhaustive treatise" and argues that Manilius likely gave a "perfunctory account of the planets' natures in the great lacuna [and then] considered his obligations duly discharged".

[118][120] These writers base their assertion on a letter sent in AD 983 by Gerbertus Aureliacensis (later Pope Sylvester II) to the Archbishop of Rheims, in which the former reports he had recently located "eight volumes about astrology by Boethius" (viii volumina Boetii de astrologia) at the abbey at Bobbio.

[120] Volk, when considering the problem of completeness, proposed several hypotheses: the work is mostly complete but internally inconsistent about which topics it will and will not consider; the lacuna in book five may have originally contained the missing information; the lacuna may be relatively small and the work is unfinished; or entire books may have originally existed but were lost over time through the "hazardous process of textual transmission".

[126][127] Furthermore, while Lucretius used De rerum natura to present a non-theistic account of creation, Manilius "was a creationist rather than a materialistic evolutionist", and he consequently refers to "one spirit" (unus spiritus, 2.64), a "divine power" (divina potentia, 3.90), a "creator" (auctor, 3.681), and a "god" (deus, 2.475) throughout his poem.

[139][140] However, due to the scribe's incompetence,[nb 8] manuscript M was riddled with mistakes, prompting Bracciolini to sarcastically remark that the new copy had to be "divined rather than read" (divinare oportet non legere).

[8][134][157] With this said, Hübner cautions that such assumptions should be considered carefully (or downright rejected, in the cases of Manetho and Pseudo-Empedocles), as the similarities may be due to a lost ancient epic precursor that Manilius and the others were all alluding to or borrowing from.

[9] Volk notes that the earliest references to Astronomica—aside from literary allusions—may be found in two Roman funerary inscriptions, both of which bear the line, "We are born to die, and our end hangs from the beginning" (nascentes morimur finisque ab origine pendet) from the poem's fourth book.

The book's purpose was to "encourage readers to discover Manilius" and expand scholarly interest in the Astronomica, since previous research of the work's poetic, scientific, and philosophical themes had been primarily limited to Germany, France, and Italy.

According to Kristine Louise Haugen, "The ambiguous phrases and extravagant circumlocutions necessitated by Manilius's hexameter verse must often have made the Astronomica seem, as it does today, rather like a trigonometry textbook rendered as a Saturday The New York Times crossword.

Housman voiced this sentiment in a dedicatory Latin poem written for the first volume of his edition that contrasted the movement of celestial objects with mortality and the fate of Manilius's work.

[148] He compared the Astronomica to a shipwreck (carmina ... naufraga), arguing that it was incomplete and imperfect, having barely survived textual transmission; Housman mused that because Manilius's ambitions of literary fame and immortality had been almost entirely dashed, his work should serve as an example of why "no man ever ought to trust the gods" (ne quis forte deis fidere vellet homo).