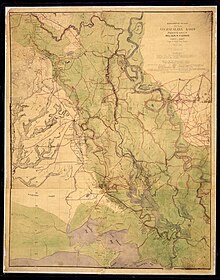

Atchafalaya Basin

Best known for its iconic cypress–tupelo swamps, at 260,000 acres (110,000 ha), this block of forest represents the largest remaining contiguous tract of coastal cypress in the United States.

[5] The Basin's thousands of acres of forest and farmland are home to the Louisiana black bear (Ursus americanus luteolus), which has been on the United States Fish and Wildlife Service threatened list since 1992.

[8] The central basin is further bordered by man-made levees designed to contain and funnel floodwaters released from the Mississippi at the Old River Control Structure and the Morganza Spillway south toward Morgan City and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico.

From then until the completion of the Old River Control Structure in 1963, the Mississippi was increasingly diverting flow into the shorter and steeper path of the Atchafalaya channel.

On May 13, 2011, in the face of a rising Mississippi River that threatened to flood New Orleans and other heavily populated parts of Louisiana, the USACE ordered the Morganza Spillway opened for the first time since 1973.

The US Geological Survey (USGS) reports that Mississippi River delta salt marshes are wetlands degrading at a rate of 29 square miles per year (2.4 km2/Ms).

In order to facilitate this emergency plan without flooding adjacent agriculture and towns, protective levees were built dividing the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway from large portions of the historic swamp boundaries.

From 1830 to 1953, the community of Bayou Chene thrived as a center for logging, hunting, trapping, and fishing in the heart of the Atchafalaya Basin.

Now buried underneath at least twelve feet of silt, Bayou Chene is one of several abandoned communities in the midst of the basin.

Robin who, while paddling through the Basin in 1803, wrote: After long sinuosities which form innumerable islands, among which the inexperienced traveler would require the thread of Ariadne in order not to wander forever, the river opens suddenly into a magnificent lake of several leagues extent.

The sudden light surprises the traveler and the beauty of the water, set about with tall trees, forms an enchanting sight.

The population rose quickly over the next twenty years, as the United States Census of 1860 counted 675 residents in the community.

[13] By the 1870s, a majority of those living along Bayou Chene were involved in logging bald cypress, tupelo, and other bottomland hardwoods in the basin.

By the early twentieth century, Bayou Chene was the center of the Atchafalya Basin's cypress and fur industry and housed many of the 1,000 full-time fisherman who fished the swamp's shallow bottoms.

[15] Writing about her family's experiences in the region, Gwen Roland describes how the community relied upon the basin's waters for everything, including transportation: Out here on the Chene, our skiffs flare out on the sides so they float high like an acorn cap; it makes them quick to steer with an extra push on one oar or the other.

[15] After years of rising waters, the community came to an end with the closing of the United States Post Office at Bayou Chene in 1952.