Salt marsh die-off

[2] Many ecologists argue that bottom-up and top-down control do not play equally critical roles in the structure and dynamics of populations in an ecosystem; however, data suggests that both bottom-up and top-down forces impact the structure of food webs and the spatial and temporal abundance and distribution of organisms (Bertness 2007),[3] although to what extent each plays a role is not fully understood.

[4] Many ecosystems in which consumer control has classically been considered trivial are dominated by plants (e.g., forests, grasslands, and salt marshes) and are usually green in appearance.

[2] Critics pointed out that the world is not always green, and that when it is, herbivores do not necessarily play an important role in structuring plant communities (Ehrlich and Birch 1967).

[11] A classic example of top-down interactions dictating community structure and function comes from Bob Paine's work in Washington, which established that removal of the starfish Pisaster triggered a trophic cascade in which the blue mussel (Mytilus) populations exploded due to release from predation pressure (Paine 1966)[12] Another influential example of top-down control emerged from Jane Lubchenco's experiments on New England rocky shores, which demonstrated that the herbivorous snail L. littorea exerts control on the diversity and succession of tide pool algal communities (Lubchenco and Menge 1978).

[13] One hypothesis that arose from Lubchenco's work (Little and Kitching 1996)[14] was that predation by the green crab (Carcinus maenas) influences rocky shore algal communities by regulating L. littorea abundances.

In salt marshes, early ecologists like Eugene Odum and John Teal sparked the current bottom-up paradigm in ecology through work on Sapelo Island, GA (U.S.A) that stressed the dominant role of physical factors like temperature, salinity, and nutrients in regulating plant primary productivity and ecosystem structure (Teal 1962, Odum 1971).

[15] A corollary of this dogma is that consumers play an unimportant or subtle role in controlling salt marsh primary production (Smalley 1960, Teal 1962).

[17][18][19] Recent work, however, has demonstrated strong top-down control of plant communities in salt marshes by a wide variety of consumers, including snails, crabs, and geese (Jefferies 1997, Bortolus and Iribarne 1999, Silliman and Bertness 2002, Holdredge et al.

[20][21][22][23] Marsh grazers also include feral horses (Furbish and Albano 1994),[24] cattle, hares, insects, and rodents, some of which are able to strongly suppress plant growth.

Consumer control is driven by the grapsid crab (Chasmagnathus granulata) in the salt marshes of Argentina and Brazil on the Atlantic coast of South America (Bortolus and Iribarne 1999).

[4] Depletion of top predators releases their prey from consumer control and leads to population declines of the next lower trophic level, often the primary producers.

[28] Trophic cascades can induce salt marsh die-off and transform green landscapes into barrens (Estes and Duggins 1995, Silliman et al.

This snail is capable of turning strands of cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) (>2.5m tall) into mudflats within 8 months, which is less than one growing season (Silliman and Bertness 2002).

[10] Other trophic cascades, such as those caused by crabs such as Chasmagnathus granulata in South America, are at least in part due to overfishing of top predators (Bortolus and Iribarne 1999, Alberti et al.

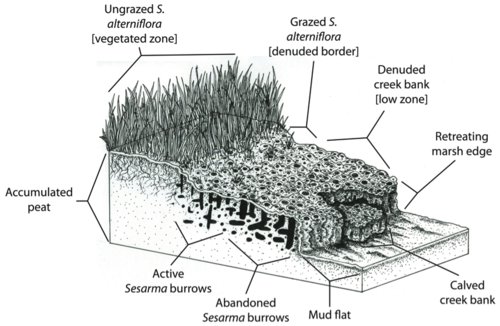

The nocturnal purple marsh crab, Sesarma reticulatum, is playing a major role in this die-off through increased burrowing and herbivory due to release from predation pressure.

These results provide evidence that Sesarma release from predation pressure by crabs and fish due to recreational overfishing by anglers is driving a trophic cascade that is responsible for extensive marsh die-off throughout southern New England (Altieri et al.

[36] Altieri and colleagues (2012)[36] further hypothesized that historic, large-scale, industrialized overexploitation of fish in the northwest Atlantic (Lotze et al. 2006)[30] increased marsh vulnerability to the effects of localized recreational fishing to the point that large-scale die off ensued, and that resultant localized die-offs could coalesce into complete, region-wide marsh die-off if overexploitation of top consumers continues (Altieri et al.

(Bertness et al. 2014a)[38] This work highlighted one particular example where top-down interactions were experimentally shown to be the primary driver of ecological community state change.

[41][42] In marine ecosystems, increased flow of nitrogen can trigger severe algal blooms, anoxic conditions, and widespread fisheries losses (Diaz & Rosenberg 2008).

[43] In salt marshes, an important interface ecosystem between land and sea, nutrient addition has been hypothesized to contribute to widespread creek die-offs (Deegan et al.

[46] Coastal ecosystems suffer from a variety of anthropogenic impacts, such as large-scale eutrophication, food web alteration, runaway consumer effects, climate change, habitat destruction, and disease.

Anthropogenic actions also can cause eutrophication, or increase the nutrient load, of marine ecosystems, through runoff into the system containing fertilizer, sewage, dishwasher soap, and other nitrogen- and phosphorus-rich substances.

Eutrophication is pervasive in coastal marine ecosystems (Lotze et al. 2006)[30] and can indirectly initiate trophic cascades and increase consumer control of plants.

[20] A major goal of ecology over the next century will be to understand how ecosystems will respond to current and future human impacts and the additive or synergistic interactions between them.

[50] Arguably the most important ecosystem service salt marshes provide is to act as natural sea barriers because grasses bind soils, prevent shoreline erosion, attenuate waves, and reduce coastal flooding (Costanza et al.

Since Spartina alterniflora is responsible for sediment binding and peat deposition (Redfield 1965),[52] cordgrass die-off may compromise the ability of salt marshes to keep pace with sea-level rise.

Despite mounting evidence to the contrary, bottom-up control remains the central dogma determining marsh management, conservation and restoration efforts.

However, global and near shore top predator depletion leading to the release of cryptic or unappreciated herbivores may be the biggest current threat to salt marshes.

Theory dependency (subconscious favoring of identifying and/or examining natural phenomena that tend to confirm rather than refute the current paradigm of a study system [Kuhn 1962][54]) and demonstration, rather than falsifying science, have been the leading culprits in this oversight.

Trophic cascades were originally thought to be rare, but it has become clear that they occur across diverse terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems at both small and large spatial and temporal scales.