History of citizenship

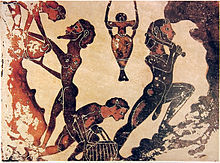

[2] While there is disagreement about when the relation of citizenship began, many thinkers point to the early city-states of ancient Greece, possibly as a reaction to the fear of slavery, although others see it as primarily a modern phenomenon dating back only a few hundred years.

In Roman times, citizenship began to take on more of the character of a relationship based on law, with less political participation than in ancient Greece but a widening sphere of who was considered to be a citizen.

This notion that ... the proper way for us to live is as citizens in communities under the rule of law ... is an idea originated by the Greeks and bequeathed by them as their greatest contribution to the rest of mankind and history.

[8] While Greeks were spread out in many separate city-states, they had many things in common in addition to shared ideas about citizenship: the Mediterranean trading world, kinship ties, the common Greek language, a shared hostility to the so-called non-Greek-speaking or barbarian peoples, belief in the prescience of the oracle at Delphi, and later on the early Olympic Games which involved generally peaceful athletic competitions between city-states.

[4] It was an elitist notion, according to Peter Riesenberg, in which small scale communities had generally similar ideas of how people should behave in society and what constituted appropriate conduct.

And it needs a political system which gives them a say on matters that concern their lives.As a consequence, the original Athenian aristocratic constitution gradually became more inappropriate, and gave way to a more inclusive arrangement.

[20] In this sense, Athenian citizenship extended beyond basic bonds such as ties of family, descent, religion, race, or tribal membership, and reached towards the idea of a civic multiethnic state built on democratic principles.

[8] Citizens had certain rights and duties: the rights included the chance to speak and vote in the common assembly,[2] to stand for public office, to serve as jurors, to be protected by the law, to own land, and to participate in public worship; duties included an obligation to obey the law, and to serve in the armed forces which could be "costly" in terms of buying or making expensive war equipment or in risking one's own life, according to Hosking.

[13]: 151 Aristotle's sense of citizenship depended on a "rigorous separation of public from private, of polis from oikos, of persons and actions from things" which allowed people to interact politically with equals.

[4]: p.17 [22] In Aristotle's conception, citizenship was possible generally in a small city-state since it required direct participation in public affairs[4]: p.18 with people knowing "one another's characters".

[4]: 128 In Aristotle's conception, humans are destined "by nature" to live in a political association and take short turns at ruling, inclusively, participating in making legislative, judicial and executive decisions.

But Aristotle's sense of "inclusiveness" was limited to adult Greek males born in the polity: women, children, slaves, and foreigners (that is, resident aliens), were generally excluded from political participation.

Geoffrey Hosking argued that Greek ideas of citizenship in the city-state, such as the principles of equality under the law, civic participation in government, and notions that "no one citizen should have too much power for too long", were carried forth into the Roman world.

[2] Through worker discontent, the plebs threatened to set up a rival city to Rome, and through negotiation around 494 BCE, won the right to have their interests represented in government by officers known as tribunes.

[2] David Burchell argued that in Cicero's time, there were too many citizens pushing to "enhance their dignitas", and the result of a "political stage" with too many actors all wanting to play a leading role, was discord.

[2][30] The problem of extreme inequality of landed wealth led to a decline in the citizen-soldier arrangement, and was one of many causes leading to the dissolution of the Republic and rule by dictators.

Some thinkers suggest that as a result of historical circumstances, western Europe evolved with two competing sources of authority—religious and secular—and that the ensuing separation of church and state was a "major step" in bringing forth the modern sense of citizenship.

[2] According to historian Andrew C. Fix, Italy in the 14th century was much more urbanized than the rest of Europe, with major populations concentrated in cities like Milan, Rome, Genoa, Pisa, Florence, Venice and Naples.

"[35] According to one theorist, the requirement that individual citizen-soldiers provide their own equipment for fighting helped to explain why Western cities evolved the concept of citizenship, while Eastern ones generally did not.

[35] And city dwellers who had fought alongside nobles in battles were no longer content with having a subordinate social status, but demanded a greater role in the form of citizenship.

[6] The early modern period saw significant social change in Great Britain in terms of the position of individuals in society and the growing power of Parliament in relation to the monarch.

These Acts set out the requirement for regular elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike much of Europe at the time, royal absolutism would not prevail.

[47] One scholar who examined pre-Revolutionary France described powerful groups which stifled citizenship and included provincial estates, guilds, military governors, courts with judges who owned their offices, independent church officials, proud nobles, financiers and tax farmers.

Discussion started of ideas (such as legal limits, definitions of monarchy and the state, parliaments and elections, an active press, public opinion) and of concepts (such as civic virtue, national unity, and social progress).

He argued that: The contingent and uneven development of a bundle of rights understood as citizenship in the early nineteenth century was heavily indebted to class conflict played out in struggles over state policy on trade and labor.Nationalism emerged.

In Meiji Japan, popular social forces exerted influence against traditional types of authority, and out of a period of negotiations and concessions by the state came a time of "expanding democracy", according to one account.

"[57] From this view, citizens are sovereign, morally autonomous beings with duties to pay taxes, obey the law, engage in business transactions, and defend the nation if it comes under attack,[53] but are essentially passive politically.

[58] But this sense of citizenship has been criticized; according to one view, it can lead to a "culture of subjects" with a "degeneration of public spirit" since economic man, or homo economicus, is too focused on material pursuits to engage in civic activity to be true citizens.

[13]: p.167 This view emphasizes the democratic participation inherent in citizenship, and can "channel legitimate frustrations and grievances" and bring people together to focus on matters of common concern and lead to a politics of empowerment, according to theorist Dora Kostakopoulou.

Feliks Gross sees 20th century America as an "efficient, pluralistic and civic system that extended equal rights to all citizens, irrespective of race, ethnicity and religion.