Public sphere

[3] Communication scholar Gerard A. Hauser defines it as "a discursive space in which individuals and groups associate to discuss matters of mutual interest and, where possible, to reach a common judgment about them".

[23]Through this work, he gave a historical-sociological account of the creation, brief flourishing, and demise of a "bourgeois" public sphere based on rational-critical debate and discussion:[24] Habermas stipulates that, due to specific historical circumstances, a new civic society emerged in the eighteenth century.

Driven by a need for open commercial arenas where news and matters of common concern could be freely exchanged and discussed—accompanied by growing rates of literacy, accessibility to literature, and a new kind of critical journalism—a separate domain from ruling authorities started to evolve across Europe.

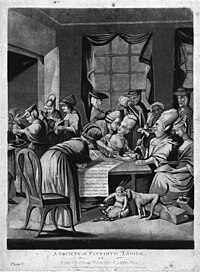

The discursive arenas, such as Britain's coffee houses, France's salons, and Germany's Tischgesellschaften "may have differed in the size and compositions of their publics, the style of their proceedings, the climate of their debates, and their topical orientations", but "they all organized discussion among people that tended to be ongoing; hence they had a number of institutional criteria in common":[26] Habermas argued that the bourgeois society cultivated and upheld these criteria.

The public sphere was well established in various locations including coffee shops and salons, areas of society where various people could gather and discuss matters that concerned them.

The coffee houses in London society at this time became the centers of art and literary criticism, which gradually widened to include even the economic and the political disputes as matters of discussion.

The emergence of a bourgeois public sphere was particularly supported by the 18th-century liberal democracy making resources available to this new political class to establish a network of institutions like publishing enterprises, newspapers and discussion forums, and the democratic press was the main tool to execute this.

The key feature of this public sphere was its separation from the power of both the church and the government due to its access to a variety of resources, both economic and social.

As Habermas argues, in due course, this sphere of rational and universalistic politics, free from both the economy and the State, was destroyed by the same forces that initially established it.

[27]Although Structural Transformation was (and is) one of the most influential works in contemporary German philosophy and political science, it took 27 years until an English version appeared on the market in 1989.

Fraser worked from Habermas' basic theory because she saw it to be "an indispensable resource" but questioned the actual structure and attempted to address her concerns.

[39][40] The concept of heteronormativity is used to describe the way in which those who fall outside of the basic male/female dichotomy of gender or whose sexual orientations are other than heterosexual cannot meaningfully claim their identities, causing a disconnect between their public selves and their private selves.

Those norms are: In all this Hauser believes a public sphere is a "discursive space in which strangers discuss issues they perceive to be of consequence for them and their group.

According to Habermas, there are two types of actors without whom no political public sphere could be put to work: professionals in the media system and politicians.

[52] For Habermas, there are five types of actors who make their appearance on the virtual stage of an established public sphere: (a) Lobbyists who represent special interest groups; (b) Advocates who either represent general interest groups or substitute for a lack of representation of marginalized groups that are unable to voice their interests effectively; (c) Experts who are credited with professional or scientific knowledge in some specialized area and are invited to give advice; (d) Moral entrepreneurs who generate public attention for supposedly neglected issues;

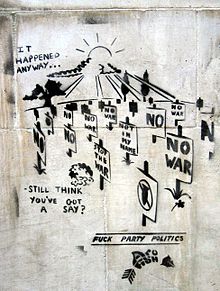

The authors argue that some scholars think the online public sphere is a space where a wide range of voices can be expressed due to the "low barrier of entry"[58] and interactivity.

His research analysed a total of 1239 videos uploaded by five news organisations and investigated the link between content and user engagement.

[62] German scholars Jürgen Gerhards and Mike S. Schäfer conducted a study in 2009 in order to establish whether the Internet offers a better and broader communication environment compared to quality newspapers.

Their intention was to analyze what actors and what sort of opinions the subject generated in both print and the Internet and verify whether the online space proved to be a more democratic public sphere, with a wider range of sources and views.

Gerhards and Schäfer say they have found "only minimal evidence to support the idea that the internet is a better communication space as compared to print media".

[63] For Gerhards and Schäfer the Internet is not an alternative public sphere because less prominent voices end up being silenced by the search engines' algorithms.

Additionally, new forms of political participation and information sources for the users emerge with the Internet that can be used, for example, in online campaigns.

Loader and Mercea point out that "individual preferences reveal an unequal spread of social ties with a few giant nodes such as Google, Yahoo, Facebook and YouTube attracting the majority of users".

The authors conclude that social media provides new opportunities for political participation; however, they warn users of the risks of accessing unreliable sources.

The Internet impacts the virtual public sphere in many ways, but is not a free utopian platform as some observers argued at the beginning of its history.

[68][69] John Thompson criticises the traditional idea of public sphere by Habermas, as it is centred mainly in face-to-face interactions.

The political function and effect of modes of public communication has traditionally continued with the dichotomy between Hegelian State and civil society.

Its third virtue is to escape from the simple dichotomy of free market versus state control that dominates so much thinking about media policy.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have, drawing on the late Michel Foucault's writings on biopolitics, suggested that we reconsider the very distinction between public and private spheres.

Hardt and Negri see the open source approaches as examples of new ways of co-operation that illustrate how economic value is not founded upon exclusive possession, but rather upon collective potentialities.