Ātman (Hinduism)

Some schools of Indian philosophy regard the Ātman as distinct from the material or mortal ego (Ahankara), the emotional aspect of the mind (Citta), and existence in an embodied form (Prakṛti).

[web 2] Ātman, sometimes spelled without a diacritic as atman in scholarly literature,[10] means "real Self" of the individual,[note 1] "innermost essence.

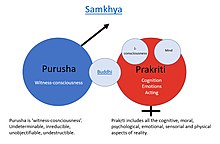

"[1][note 2] In Hinduism, Atman refers to the self-existent essence of human beings, the observing pure consciousness or witness-consciousness as exemplified by the Purusha of Samkhya.

It is distinct from the ever-evolving embodied individual being (jivanatman) embedded in material reality, exemplified by the prakriti of Samkhya, and characterized by Ahamkara (ego, non-spiritual psychological I-ness Me-ness), mind (citta, manas), and all the defiling kleshas (habits, prejudices, desires, impulses, delusions, fads, behaviors, pleasures, sufferings and fears).

[17][18] As Puchalski states, "the ultimate goal of Hindu religious life is to transcend individuality, to realize one's own true nature", the inner essence of oneself, which is divine and pure.

[23] The Upanishads say that Atman denotes "the ultimate essence of the universe" as well as "the vital breath in human beings", which is "imperishable Divine within" that is neither born nor does it die.

It [Ātman] is also identified with the intellect, the Manas (mind), and the vital breath, with the eyes and ears, with earth, water, air, and ākāśa (sky), with fire and with what is other than fire, with desire and the absence of desire, with anger and the absence of anger, with righteousness and unrighteousness, with everything — it is identified, as is well known, with this (what is perceived) and with that (what is inferred).

[31] Along with the Brihadāranyaka, all the earliest and middle Upanishads discuss Ātman as they build their theories to answer how man can achieve liberation, freedom and bliss.

Katha Upanishad, in Book 1, hymns 3.3-3.4, describes the widely cited proto-Samkhya analogy of chariot for the relation of "Soul, Self" to body, mind and senses.

[33] In Bhagavad Gita verses 10-30 of the second chapter, Krishna urges Arjuna to understand the indestructible nature of the atman, emphasizing that it transcends the finite body it inhabits.

Krishna emphasizes the eternal existence of the soul by explaining that even as it undergoes various life stages and changes bodies it remains unaffected.

[36][37][38] All major orthodox schools of Hinduism – Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisesika, Mimamsa, and Vedanta – accept the foundational premise of the Vedas and Upanishads that "Ātman exists."

[12] The Yogasutra of Patanjali, the foundational text of Yoga school of Hinduism, mentions Atma in multiple verses, and particularly in its last book, where Samadhi is described as the path to self-knowledge and kaivalya.

Nyaya scholars defined Ātman as an imperceptible substance that is the substrate of human consciousness, manifesting itself with or without qualities such as desires, feelings, perception, knowledge, understanding, errors, insights, sufferings, bliss, and others.

One, Nyaya scholars went beyond holding it as "self evident" and offered rational proofs, consistent with their epistemology, in their debates with Buddhists, that "Atman exists".

[50][51] Nyayasutra, a 2nd-century CE foundational text of Nyaya school of Hinduism, states that Atma is a proper object of human knowledge.

[53] The Vaisheshika school of Hinduism, using its non-theistic theories of atomistic naturalism, posits that Ātman is one of the four eternal non-physical[54] substances without attributes, the other three being kāla (time), dik (space) and manas (mind).

Time and space are indivisible reality, but human mind prefers to divide them to comprehend past, present, future, relative place of other substances and beings, direction and its own coordinates in the universe.

[12] Ātman, in the ritualism-based Mīmāṃsā school of Hinduism, is an eternal, omnipresent, inherently active essence that is identified as I-consciousness.

[61][65] Atman is the universal principle, one eternal undifferentiated self-luminous consciousness, the truth asserts Advaita Hinduism.

[72] The Dvaita school, therefore, in contrast to the monistic position of Advaita, advocates a version of monotheism wherein Brahman is made synonymous with Vishnu (or Narayana), distinct from numerous individual Atmans.

Applying the disidentification of 'no-self' to the logical end,[5][8][7] Buddhism does not assert an unchanging essence, any "eternal, essential and absolute something called a soul, self or atman,"[note 3] According to Jayatilleke, the Upanishadic inquiry fails to find an empirical correlate of the assumed Atman, but nevertheless assumes its existence,[5] and, states Mackenzie, Advaitins "reify consciousness as an eternal self.

"[73] In contrast, the Buddhist inquiry "is satisfied with the empirical investigation which shows that no such Atman exists because there is no evidence" states Jayatilleke.

"[6] While the skandhas are regarded is impermanent (anatman) and sorrowfull (dukkha), the existence of a permanent, joyful and unchanging self is neither acknowledged nor explicitly denied.

[8]Nevertheless, Atman-like notions can also be found in Buddhist texts chronologically placed in the 1st millennium of the Common Era, such as the Mahayana tradition's Tathāgatagarbha sūtras suggest self-like concepts, variously called Tathagatagarbha or Buddha nature.

[80][note 4][81][82] The Dhammakaya Movement teaching that nirvana is atta (atman) has been criticized as heretical in Buddhism by Prayudh Payutto, a well-known scholar monk, who added that 'Buddha taught nibbana as being non-self".

[85] The earliest Dharmasutras of Hindus recite Atman theory from the Vedic texts and Upanishads,[87] and on its foundation build precepts of dharma, laws and ethics.

– 1.8.22.2-7 Freedom from anger, from excitement, from rage, from greed, from perplexity, from hypocrisy, from hurtfulness (from injury to others); Speaking the truth, moderate eating, refraining from calumny and envy, sharing with others, avoiding accepting gifts, uprightness, forgiveness, gentleness, tranquility, temperance, amity with all living creatures, yoga, honorable conduct, benevolence and contentedness – These virtues have been agreed upon for all the ashramas; he who, according to the precepts of the sacred law, practices these, becomes united with the Universal Self.

8th century BCE),[91] then becomes central in the texts of Hindu philosophy, entering the dharma codes of ancient Dharmasutras and later era Manu-Smriti.

He [the self] prevades all, resplendent, bodiless, woundless, without muscles, pure, untouched by evil; far-seeing, transcendent, self-being, disposing ends through perpetual ages.