Wisdom

Throughout history, wisdom has been regarded as a key virtue in philosophy, religion, and psychology, representing the ability to understand and respond to reality in a balanced and thoughtful manner.

Unlike intelligence, which primarily concerns problem-solving and reasoning, wisdom involves a deeper comprehension of human nature, moral principles, and the long-term consequences of actions.

As artificial intelligence and data-driven decision-making play a growing role in shaping human life, discussions on wisdom remain relevant, emphasizing the importance of judgment, ethical responsibility, and long-term planning.

He argued that true wisdom involves questioning and refining beliefs rather than assuming certainty: τούτου μὲν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐγὼ σοφώτερός εἰμι: κινδυνεύει μὲν γὰρ ἡμῶν οὐδέτερος οὐδὲν καλὸν κἀγαθὸν εἰδέναι, ἀλλ᾽ οὗτος μὲν οἴεταί τι εἰδέναι οὐκ εἰδώς, ἐγὼ δέ, ὥσπερ οὖν οὐκ οἶδα, οὐδὲ οἴομαι: ἔοικα γοῦν τούτου γε σμικρῷ τινι αὐτῷ τούτῳ σοφώτερος εἶναι, ὅτι ἃ μὴ οἶδα οὐδὲ οἴομαι εἰδέναι.

This permeates Plato's dialogues; in The Republic the leaders of his proposed utopia are philosopher kings who, through education and contemplation, attain a deep understanding of justice and the Forms, and possess the courage to act accordingly.

was the first to differentiate between two types of wisdom: Aristotle saw phronesis as essential for ethical living, arguing that virtuous actions require both knowledge and experience.

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) viewed wisdom as knowledge aligned with God's eternal truth, distinguishing it from mere worldly intelligence.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) viewed wisdom as a confrontation with the absurd condition of life and the freedom to create meaning in a world devoid of inherent purpose.

[51] Albert Camus (1913–1960) echoed these ideas in The Myth of Sisyphus, arguing that wisdom lies in accepting life's absurdity and choosing to live meaningfully despite its challenges.

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) argued that ideas of wisdom are shaped by power structures and are inherently subjective, often serving to reinforce dominant ideologies.

[58] Wisdom in Confucianism is practical and moral, requiring individuals to cultivate righteousness (yi, 義) and ritual propriety (li, 禮) in order to contribute to a stable society.

[61] Xunzi (c. 310–235 BCE), by contrast, saw wisdom as the product of strict discipline and adherence to ritual, believing that human nature is inherently flawed and must be shaped through deliberate effort.

[62] The Confucian approach to wisdom remains influential in East Asian ethics, education, and leadership philosophy, continuing to shape modern discussions on morality and governance.

In Theravāda Buddhism, wisdom is developed through vipassanā (insight meditation), leading to the realization of impermanence (anicca), suffering (duḥkha), and non-self (anattā).

In Chinese Buddhism, the idea of wisdom is closely linked to its Indian equivalent as it appears for instance in certain conceptual continuities that exist between Asanga, Vasubandhu and Xuanzang.

Unlike the empirical knowledge (vidyā, विद्या) gained through sensory experience, wisdom in Hinduism involves insight into the ultimate nature of reality (Brahman, ब्रह्मन्) and the self (Ātman, आत्मन्).

[73] The Upanishads, foundational texts of Hindu thought, describe wisdom as the realization that all worldly distinctions are illusions (maya, माया), and that the self is one with the infinite consciousness of Brahman.

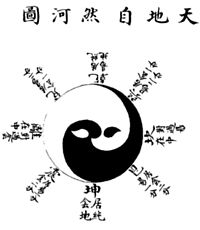

The Zhuangzi text, attributed to Zhuang Zhou (c. 4th century BCE), presents wisdom as a state of effortless flow (wu wei), where one aligns with the spontaneous patterns of nature rather than imposing human will.

[84] In Tao Te Ching (道德經), attributed to Laozi (6th century BCE), wisdom is described as yielding like water, able to overcome obstacles through gentleness rather than force.

[85] This perspective aligns with Taoist ethics, which discourage aggression and rigid control, instead promoting a harmonious existence in sync with nature’s rhythms.

Taoist sages are often depicted as detached from worldly concerns, seeking a deeper, wordless understanding of existence that transcends conventional logic.

[92][38] These processes include recognizing the limits of one's own knowledge, acknowledging uncertainty and change, attention to context and the bigger picture, and integrating different perspectives of a situation.

[104] Grossmann says contextual factors – such as culture, experiences, and social situations – influence the understanding, development, and propensity of wisdom, with implications for training and educational practice.

In 2021 Dr. Dilip V. Jeste and his colleagues created a 7-question survey (SD-WISE-7) testing seven components: acceptance of diverse perspectives, decisiveness, emotional regulation, prosocial behaviors, self-reflection, social advising, and (to a lesser degree) spirituality.

[119] The character Master Yoda from the films evokes the trope of the wise old man,[120] and he is frequently quoted, analogously to Chinese thinkers or Eastern sages in general.

[125] In Zoroastrianism, the order of the universe and morals is called asha (in Avestan, truth, righteousness), which is determined by this omniscient Thought and also considered a deity emanating from Ahura (Amesha Spenta).

[126] It says in Yazna 31:[127] To him shall the best befall, who, as one that knows, speaks to me Right's truthful word of Welfare and of Immortality; even the Dominion of Mazda which Good Thought shall increase for him.

[130] According to Valentinian Gnosticism, Sophia’s fall led to the creation of the material world, but through wisdom, the soul could transcend illusion and return to the divine realm.

[162] In another famous account, Odin hanged himself for nine nights from Yggdrasil, the World Tree that unites all the realms of existence, suffering from hunger and thirst and finally wounding himself with a spear until he gained the knowledge of runes for use in casting powerful magic.

This nickname originated from the classical tradition – the Hippocratic writings used the term sóphronistér (in Greek, related to the meaning of moderation or teaching a lesson), and in Latin dens sapientiae (wisdom tooth).