Atmospheric refraction

Such refraction can also raise or lower, or stretch or shorten, the images of distant objects without involving mirages.

If observations of objects near the horizon cannot be avoided, it is possible to equip an optical telescope with control systems to compensate for the shift caused by the refraction.

If the dispersion is also a problem (in case of broadband high-resolution observations), atmospheric refraction correctors (made from pairs of rotating glass prisms) can be employed as well.

This causes suboptimal seeing conditions, such as the twinkling of stars and various deformations of the Sun's apparent shape soon before sunset or after sunrise.

Georg Constantin Bouris measured refraction of as much of 4° for stars on the horizon at the Athens Observatory[6] and, during his ill-fated Endurance expedition, Sir Ernest Shackleton recorded refraction of 2°37′:[7] “The sun which had made ‘positively his last appearance’ seven days earlier surprised us by lifting more than half its disk above the horizon on May 8.

Because atmospheric refraction is nominally 34′ on the horizon, but only 29′ at 0.5° above it, the setting or rising sun seems to be flattened by about 5′ (about 1/6 of its apparent diameter).

Closer to the horizon, actual measurements of the changes with height of the local temperature gradient need to be employed in the numerical integration.

The simpler formulations involved nothing more than the temperature and pressure at the observer, powers of the cotangent of the apparent altitude of the astronomical body and in the higher order terms, the height of a fictional homogeneous atmosphere.

Comstock considered that this formula gave results within one arcsecond of Bessel's values for refraction from 15° above the horizon to the zenith.

[18] A further expansion in terms of the third power of the cotangent of the apparent altitude incorporates H0, the height of the homogeneous atmosphere, in addition to the usual conditions at the observer:[17] A version of this formula is used in the International Astronomical Union's Standards of Fundamental Astronomy; a comparison of the IAU's algorithm with more rigorous ray-tracing procedures indicated an agreement within 60 milliarcseconds at altitudes above 15°.

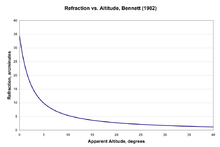

[19] Bennett[20] developed another simple empirical formula for calculating refraction from the apparent altitude which gives the refraction R in arcminutes: This formula is used in the U. S. Naval Observatory's Vector Astrometry Software,[21] and is reported to be consistent with Garfinkel's[22] more complex algorithm within 0.07′ over the entire range from the zenith to the horizon.

Turbulence in Earth's atmosphere scatters the light from stars, making them appear brighter and fainter on a time-scale of milliseconds.

Turbulence also causes small, sporadic motions of the star image, and produces rapid distortions in its structure.

[24][25] Since the line of sight in terrestrial refraction passes near the earth's surface, the magnitude of refraction depends chiefly on the temperature gradient near the ground, which varies widely at different times of day, seasons of the year, the nature of the terrain, the state of the weather, and other factors.

Multiplying half the curvature by the length of the ray path gives the angle of refraction at the observer.

This yields where L is the length of the line of sight in meters and Ω is the refraction at the observer measured in arc seconds.