Kelvin

[1][5] The 19th century British scientist Lord Kelvin first developed and proposed the scale.

[6] The kelvin was formally added to the International System of Units in 1954, defining 273.16 K to be the triple point of water.

[2][7][8] The 2019 revision of the SI now defines the kelvin in terms of energy by setting the Boltzmann constant to exactly 1.380649×10−23 joules per kelvin;[2] every 1 K change of thermodynamic temperature corresponds to a thermal energy change of exactly 1.380649×10−23 J.

During the 18th century, multiple temperature scales were developed,[9] notably Fahrenheit and centigrade (later Celsius).

Instead, they chose defining points within the range of human experience that could be reproduced easily and with reasonable accuracy, but lacked any deep significance in thermal physics.

In the case of the Celsius scale (and the long since defunct Newton scale and Réaumur scale) the melting point of ice served as such a starting point, with Celsius being defined (from the 1740s to the 1940s) by calibrating a thermometer such that: This definition assumes pure water at a specific pressure chosen to approximate the natural air pressure at sea level.

From 1787 to 1802, it was determined by Jacques Charles (unpublished), John Dalton,[10][11] and Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac[12] that, at constant pressure, ideal gases expanded or contracted their volume linearly (Charles's law) by about 1/273 parts per degree Celsius of temperature's change up or down, between 0 °C and 100 °C.

In 1848, William Thomson, who was later ennobled as Lord Kelvin, published a paper On an Absolute Thermometric Scale.

[14] For example, in a footnote, Thomson derived the value of −273 °C for absolute zero by calculating the negative reciprocal of 0.00366—the coefficient of thermal expansion of an ideal gas per degree Celsius relative to the ice point.

[15] This derived value agrees with the currently accepted value of −273.15 °C, allowing for the precision and uncertainty involved in the calculation.

The scale was designed on the principle that "a unit of heat descending from a body A at the temperature T° of this scale, to a body B at the temperature (T − 1)°, would give out the same mechanical effect, whatever be the number T."[16] Specifically, Thomson expressed the amount of work necessary to produce a unit of heat (the thermal efficiency) as

[19] That same year, James Prescott Joule suggested to Thomson that the true formula for Carnot's function was[20]

[22] Thomson was initially skeptical of the deviations of Joule's formula from experiment, stating "I think it will be generally admitted that there can be no such inaccuracy in Regnault's part of the data, and there remains only the uncertainty regarding the density of saturated steam".

[24] Thomson arranged numerous experiments in coordination with Joule, eventually concluding by 1854 that Joule's formula was correct and the effect of temperature on the density of saturated steam accounted for all discrepancies with Regnault's data.

[28] In 1854, Thomson and Joule thus formulated a second absolute scale that was more practical and convenient, agreeing with air thermometers for most purposes.

[29] Specifically, "the numerical measure of temperature shall be simply the mechanical equivalent of the thermal unit divided by Carnot's function.

, one obtains the general principle of an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale for the Carnot engine,

[6] In 1873, William Thomson's older brother James coined the term triple point[34] to describe the combination of temperature and pressure at which the solid, liquid, and gas phases of a substance were capable of coexisting in thermodynamic equilibrium.

While any two phases could coexist along a range of temperature-pressure combinations (e.g. the boiling point of water can be affected quite dramatically by raising or lowering the pressure), the triple point condition for a given substance can occur only at a single pressure and only at a single temperature.

By the 1940s, the triple point of water had been experimentally measured to be about 0.6% of standard atmospheric pressure and very close to 0.01 °C per the historical definition of Celsius then in use.

[35] In 1954, with absolute zero having been experimentally determined to be about −273.15 °C per the definition of °C then in use, Resolution 3 of the 10th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) introduced a new internationally standardized Kelvin scale which defined the triple point as exactly 273.15 + 0.01 = 273.16 degrees Kelvin.

[4][44][45] In 2005, the CIPM began a programme to redefine the kelvin (along with other SI base units) using a more experimentally rigorous method.

The redefinition was further postponed in 2014, pending more accurate measurements of the Boltzmann constant in terms of the current definition,[48] but was finally adopted at the 26th CGPM in late 2018, with a value of kB = 1.380649×10−23 J⋅K−1.

[49][46][1][2][4][50] In fundamental physics, the mapping E=kBT which converts between the characteristic microscopic energy and the macroscopic temperature scale is often simplified by using natural units which set the Boltzmann constant to unity.

[51] For scientific purposes, the redefinition's main advantage is in allowing more accurate measurements at very low and very high temperatures, as the techniques used depend on the Boltzmann constant.

The kelvin now only depends on the Boltzmann constant and universal constants (see 2019 SI unit dependencies diagram), allowing the kelvin to be expressed as:[2] For practical purposes, the redefinition was unnoticed; enough digits were used for the Boltzmann constant to ensure that 273.16 K has enough significant digits to contain the uncertainty of water's triple point[54] and water still normally freezes at 0 °C[55] to a high degree of precision.

But before the redefinition, the triple point of water was exact and the Boltzmann constant had a measured value of 1.38064903(51)×10−23 J/K, with a relative standard uncertainty of 3.7×10−7.

[54] Afterward, the Boltzmann constant is exact and the uncertainty is transferred to the triple point of water, which is now 273.1600(1) K.[a] The new definition officially came into force on 20 May 2019, the 144th anniversary of the Metre Convention.

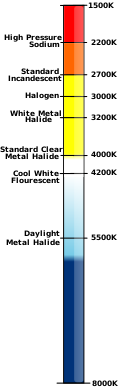

Digital cameras and photographic software often use colour temperature in K in edit and setup menus.

The simple guide is that higher colour temperature produces an image with enhanced white and blue hues.