Horizon

This curve divides all viewing directions based on whether it intersects the relevant body's surface or not.

With respect to Earth, the center of the true horizon is below the observer and below sea level.

[2] When observed from very high standpoints, such as a space station, the horizon is much farther away and it encompasses a much larger area of Earth's surface.

In this case, the horizon would no longer be a perfect circle, not even a plane curve such as an ellipse, especially when the observer is above the equator, as the Earth's surface can be better modeled as an oblate ellipsoid than as a sphere.

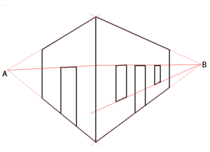

In many contexts, especially perspective drawing, the curvature of the Earth is disregarded and the horizon is considered the theoretical line to which points on any horizontal plane converge (when projected onto the picture plane) as their distance from the observer increases.

For observers near sea level, the difference between this geometrical horizon (which assumes a perfectly flat, infinite ground plane) and the true horizon (which assumes a spherical Earth surface) is imperceptible to the unaided eye.

In this equation, Earth's surface is assumed to be perfectly spherical, with R equal to about 6,371 kilometres (3,959 mi).

Assuming no atmospheric refraction and a spherical Earth with radius R=6,371 kilometres (3,959 mi): On terrestrial planets and other solid celestial bodies with negligible atmospheric effects, the distance to the horizon for a "standard observer" varies as the square root of the planet's radius.

If the Earth is assumed to be a featureless sphere (rather than an oblate spheroid) with no atmospheric refraction, then the distance to the horizon can easily be calculated.

With referring to the second figure at the right leads to the following: The exact formula above can be expanded as: where R is the radius of the Earth (R and h must be in the same units).

If the observer is close to the surface of the Earth, then it is valid to disregard h in the term (2R + h), and the formula becomes- Using kilometres for d and R, and metres for h, and taking the radius of the Earth as 6371 km, the distance to the horizon is Using imperial units, with d and R in statute miles (as commonly used on land), and h in feet, the distance to the horizon is If d is in nautical miles, and h in feet, the constant factor is about 1.06, which is close enough to 1 that it is often ignored, giving: These formulas may be used when h is much smaller than the radius of the Earth (6371 km or 3959 mi), including all views from any mountaintops, airplanes, or high-altitude balloons.

If h is significant with respect to R, as with most satellites, then the approximation is no longer valid, and the exact formula is required.

The maximum visible zenith angle occurs when the ray is tangent to Earth's surface; from triangle OCG in the figure at right, where

Suppose an observer's eye is 10 metres above sea level, and he is watching a ship that is 20 km away.

If the ground (or water) surface is colder than the air above it, a cold, dense layer of air forms close to the surface, causing light to be refracted downward as it travels, and therefore, to some extent, to go around the curvature of the Earth.

As an approximate compensation for refraction, surveyors measuring distances longer than 100 meters subtract 14% from the calculated curvature error and ensure lines of sight are at least 1.5 metres from the ground, to reduce random errors created by refraction.

However, Earth has an atmosphere of air, whose density and refractive index vary considerably depending on the temperature and pressure.

This makes the air refract light to varying extents, affecting the appearance of the horizon.

[2] For instance, if an observer is standing on seashore, with eyes 1.70 m above sea level, according to the simple geometrical formulas given above the horizon should be 4.7 km away.

This correction can be, and often is, applied as a fairly good approximation when atmospheric conditions are close to standard.

In extreme cases, usually in springtime, when warm air overlies cold water, refraction can allow light to follow the Earth's surface for hundreds of kilometres.

For radar (e.g. for wavelengths 300 to 3 mm i.e. frequencies between 1 and 100 GHz) the radius of the Earth may be multiplied by 4/3 to obtain an effective radius giving a factor of 4.12 in the metric formula i.e. the radar horizon will be 15% beyond the geometrical horizon or 7% beyond the visual.

are related by A much simpler approach, which produces essentially the same results as the first-order approximation described above, uses the geometrical model but uses a radius R′ = 7/6 RE.

But Brook Taylor (1719) indicated that the horizon plane determined by O and the horizon was like any other plane: The peculiar geometry of perspective where parallel lines converge in the distance, stimulated the development of projective geometry which posits a point at infinity where parallel lines meet.