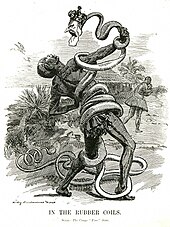

Atrocities in the Congo Free State

Combined with epidemic disease, famine, and falling birth rates caused by these disruptions, the atrocities contributed to a sharp decline in the Congolese population.

At the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the European powers recognized the claims of a supposedly philanthropic organisation run by Leopold II, to most of the Congo Basin region.

Between 1891 and 1906, the companies were allowed free rein to exploit the concessions, with the result being that forced labour and violent coercion were used to collect the rubber cheaply and maximise profit.

[2] Politically, however, colonisation was unpopular in Belgium as it was perceived as a risky and expensive gamble with no obvious benefit to the country and his many attempts to persuade politicians met with little success.

[2] Determined to look for a colony for himself and inspired by recent reports from central Africa, Leopold began patronising a number of leading explorers, including Henry Morton Stanley.

[16][17] All vacant land, including forests and areas not under cultivation, was decreed to be "uninhabited" and thus in the possession of the state, leaving many of the Congo's resources (especially rubber and ivory) under direct colonial ownership.

[23] However, the desire to maximise rubber collection, and hence the state's profits, meant that the centrally enforced demands were often set arbitrarily without considering the number of workers or their welfare.

[13] The lack of a developed bureaucracy to oversee any commercial methods produced an atmosphere of "informality" throughout the state in regard to the operation of enterprises, which in turn facilitated abuses.

Meanwhile, the Force Publique were required to provide the hand of their victims as proof when they had shot and killed someone, as it was believed that they would otherwise use the munitions (imported from Europe at considerable cost) for hunting or to stockpile them for mutiny.

Native states, notably Msiri's Yeke Kingdom, the Zande Federation, and Swahili-speaking territory in the eastern Congo under slave trader Tippu Tip, refused to recognise colonial authority and were defeated by the Force Publique with great brutality, during the Congo–Arab War.

This in turn meant that the women had to continue to plant worn-out fields resulting in lower yields, a problem aggravated by company sentries stealing crops and farm animals.

[52] After a brutally suppressed rebellion that followed the completion of the war, a young Belgian officer described the subsequent consumption of the victims' bodies as "horrible but exceedingly useful and hygienic".

[54] When sending out "punitive expeditions" against villages unwilling or unable to fulfil the government's exorbitant rubber quota, Free State officials nevertheless repeatedly turned a blind eye both to arbitrary killings of those considered guilty as well as to the "cannibal feast[s]" celebrated by native soldiers that sometimes followed.

[56][57][58] I suggest that it is impossible to separate deaths caused by massacre and starvation from those due to the pandemic of sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis) which decimated central Africa at the time.

[15] The historian Adam Hochschild argued that the dramatic fall in the Free State population was the result of a combination of "murder", "starvation, exhaustion and exposure", "disease" and "a plummeting birth rate".

Diseases imported by Arab traders, European colonists and African porters ravaged the Congolese population and "greatly exceeded" the numbers killed by violence.

[59] Nevertheless, historian Roger Anstey wrote that "a strong strand of local, oral tradition holds the rubber policy to have been a greater cause of death and depopulation than either the scourge of sleeping sickness or the periodic ravages of smallpox.

Vansina, however, notes that precolonial societies had high birth and death rates, leading to a great deal of natural population fluctuation over time.

Hochschild cites several recent independent lines of investigation, by anthropologist Jan Vansina and others, that examine local sources (police records, religious records, oral traditions, genealogies, personal diaries), which generally agree with the assessment of the 1919 Belgian government commission: roughly half the population perished during the Free State period, based on numbers from the rubber provinces.

[90] Generally, works based on the highest numbers have often been discredited as "wild" and "unsubstantiated", whereas authors who point out the lack of reliable demographic data are questioned by others, calling them "minimalists", "agnosticists" and "revisionists" who allegedly "seek to downplay or minimize the atrocities".

Notable members of the campaign included the novelists Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad and Arthur Conan Doyle as well as Belgian socialists such as Emile Vandervelde.

[100] Free State officials also defended themselves against allegations that exploitative policies were causing severe population decline in the Congo by attributing the losses to smallpox and sleeping sickness.

[103] Conditions for the indigenous population improved dramatically with the partial suppression of forced labour, although many officials who had formerly worked for the Free State were retained in their posts long after annexation.

[104] Instead of mandating labour for colonial enterprises directly, the Belgian administration used a coercive tax that deliberately pressured Congolese to find work with European employers to procure the necessary funds to make the payments.

[72] Sociologist Rhoda Howard-Hassmann stated that because the Congolese were not killed in a systematic fashion according to this criterion, "technically speaking, this was not genocide even in a legally retroactive sense.

[115][c] Historians have argued that comparisons drawn in the press by some between the death toll of the Free State atrocities and the Holocaust during World War II have been responsible for creating undue confusion over the issue of terminology.

"[120] According to historian Timothy J. Stapleton, "Those who easily apply the term genocide to Leopold's regime seem to do so purely on the basis of its obvious horror and the massive numbers of people who may have perished.

[64] These "native militia" were described by Lemkin as "an unorganized and disorderly rabble of savages whose only recompense was what they obtained from looting, and when they were cannibals, as was usually the case, in eating the foes against whom they were sent".

[124][125] The legacy of the population decline of Leopold's reign left the subsequent colonial government with a severe labour shortage and it often had to resort to mass migrations to provide workers to emerging businesses.

[129][130] In 2020, following the murder of George Floyd in the United States and the subsequent protests, numerous statues of Leopold II in Belgium were vandalised as a criticism of the atrocities of his rule in the Congo.