Harmonic series (music)

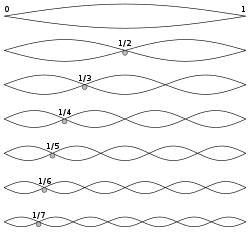

Pitched musical instruments are often based on an acoustic resonator such as a string or a column of air, which oscillates at numerous modes simultaneously.

The musical timbre of a steady tone from such an instrument is strongly affected by the relative strength of each harmonic.

The piano, one of the most important instruments of western tradition, contains a certain degree of inharmonicity among the frequencies generated by each string.

Unpitched, or indefinite-pitched instruments, such as cymbals and tam-tams make sounds (produce spectra) that are rich in inharmonic partials and may give no impression of implying any particular pitch.

It is mostly the relative strength of the different overtones that give an instrument its particular timbre, tone color, or character.

[6][failed verification] Similar arguments apply to vibrating air columns in wind instruments (for example, "the French horn was originally a valveless instrument that could play only the notes of the harmonic series"[7]), although these are complicated by having the possibility of anti-nodes (that is, the air column is closed at one end and open at the other), conical as opposed to cylindrical bores, or end-openings that run the gamut from no flare, cone flare, or exponentially shaped flares (such as in various bells).

Thus shorter-wavelength, higher-frequency waves occur with varying prominence and give each instrument its characteristic tone quality.

But because human ears respond to sound nonlinearly, higher harmonics are perceived as "closer together" than lower ones.

On the other hand, the octave series is a geometric progression (2f, 4f, 8f, 16f, ...), and people perceive these distances as "the same" in the sense of musical interval.

In terms of what one hears, each successively higher octave in the harmonic series is divided into increasingly "smaller" and more numerous intervals.

In the late 1930s, composer Paul Hindemith ranked musical intervals according to their relative dissonance based on these and similar harmonic relationships.

The lowest combination tone (100 Hz) is a seventeenth (two octaves and a major third) below the lower (actual sounding) note of the tritone.

All the intervals succumb to similar analysis as has been demonstrated by Paul Hindemith in his book The Craft of Musical Composition, although he rejected the use of harmonics from the seventh and beyond.

The relative amplitudes (strengths) of the various harmonics primarily determine the timbre of different instruments and sounds, though onset transients, formants, noises, and inharmonicities also play a role.

The saxophone's resonator is conical, which allows the even-numbered harmonics to sound more strongly and thus produces a more complex tone.