Auditory system

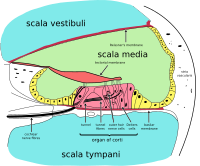

The tectorial membrane (TM) helps facilitate cochlear amplification by stimulating OHC (direct) and IHC (via endolymph vibrations).

Stellate (chopper) cells encode sound spectra (peaks and valleys) by spatial neural firing rates based on auditory input strength (rather than frequency).

Octopus cells have close to the best temporal precision while firing, they decode the auditory timing code.

Fusiform cells integrate information to determine spectral cues to locations (for example, whether a sound originated from in front or behind).

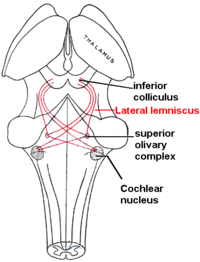

Ventral nuclei of lateral lemniscus help the inferior colliculus (IC) decode amplitude modulated sounds by giving both phasic and tonic responses (short and long notes, respectively).

Beyond multi-sensory integration IC responds to specific amplitude modulation frequencies, allowing for the detection of pitch.

[20][21] Rostromedial and ventrolateral prefrontal cortices are involved in activation during tonal space and storing short-term memories, respectively.

[22] The Heschl's gyrus/transverse temporal gyrus includes Wernicke's area and functionality, it is heavily involved in emotion-sound, emotion-facial-expression, and sound-memory processes.

This wave information travels across the air-filled middle ear cavity via a series of delicate bones: the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil) and stapes (stirrup).

The organ of Corti is located in this duct on the basilar membrane, and transforms mechanical waves to electric signals in neurons.

[citation needed] The plan view of the human cochlea (typical of all mammalian and most vertebrates) shows where specific frequencies occur along its length.

In some species, such as bats and dolphins, the relationship is expanded in specific areas to support their active sonar capability.

The organ of Corti forms a ribbon of sensory epithelium which runs lengthwise down the cochlea's entire scala media.

The journey of countless nerves begins with this first step; from here, further processing leads to a panoply of auditory reactions and sensations.

Inner hair cells are the mechanoreceptors for hearing: they transduce the vibration of sound into electrical activity in nerve fibers, which is transmitted to the brain.

Stretching and compressing, the tip links may open an ion channel and produce the receptor potential in the hair cell.

[29] The region of the basilar membrane supplying the inputs to a particular afferent nerve fibre can be considered to be its receptive field.

[30] The trapezoid body is a bundle of decussating fibers in the ventral pons that carry information used for binaural computations in the brainstem.

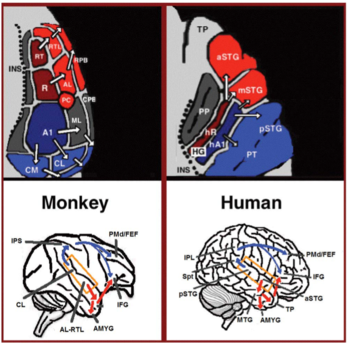

The superior temporal gyrus contains several important structures of the brain, including Brodmann areas 41 and 42, marking the location of the primary auditory cortex, the cortical region responsible for the sensation of basic characteristics of sound such as pitch and rhythm.

We know from research in nonhuman primates that the primary auditory cortex can probably be divided further into functionally differentiable subregions.

[40] Neurons integrating information from the two ears have receptive fields covering a particular region of auditory space.

The frontotemporal system underlying auditory perception allows us to distinguish sounds as speech, music, or noise.

In humans, the auditory dorsal stream in the left hemisphere is also responsible for speech repetition and articulation, phonological long-term encoding of word names, and verbal working memory.

Proper function of the auditory system is required to able to sense, process, and understand sound from the surroundings.

Difficulty in sensing, processing and understanding sound input has the potential to adversely impact an individual's ability to communicate, learn and effectively complete routine tasks on a daily basis.

[42] In children, early diagnosis and treatment of impaired auditory system function is an important factor in ensuring that key social, academic and speech/language developmental milestones are met.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

.