August Weismann

Fellow German Ernst Mayr ranked him as the second most notable evolutionary theorist of the 19th century, after Charles Darwin.

[3] However, a careful reading of Weismann's work over the span of his entire career shows that he had more nuanced views, insisting, like Darwin, that a variable environment was necessary to cause variation in the hereditary material.

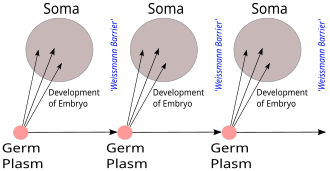

[4] The idea of the Weismann barrier is central to the modern synthesis of the early 20th century, though scholars do not express it today in the same terms.

In Weismann's opinion the largely random process of mutation, which must occur in the gametes (or stem cells that make them) is the only source of change for natural selection to work on.

[6] Weismann was born a son of high school teacher Johann (Jean) Konrad Weismann (1804–1880), a graduate of ancient languages and theology, and his wife Elise (1803–1850), née Lübbren, the daughter of the county councillor and mayor of Stade, on 17 January 1834 in Frankfurt am Main.

Weismann successfully submitted two manuscripts, one about hippuric acid in herbivores, and one about the salt content of the Baltic Sea, and won two prizes.

Microscopical work, however, became impossible to him owing to impaired eyesight, and he turned his attention to wider problems of biological inquiry.

After this work, Weismann accepted evolution as a fact on a par with the fundamental assumptions of astronomy (e.g. Heliocentrism).

Eduard Strasburger, Walther Flemming, Heinrich von Waldeyer and the Belgian Edouard Van Beneden laid the basis for the cytology and cytogenetics of the 20th century.

Walther Flemming, the founder of cytogenetics, named mitosis, and pronounced "omnis nucleus e nucleo" (which means the same as Strasburger's dictum).

He also wrote, "if every variation is regarded as a reaction of the organism to external conditions, as a deviation of the inherited line of development, it follows that no evolution can occur without a change of the environment".

For instance, the existence of non-reproductive castes of ants, such as workers and soldiers, cannot be explained by inheritance of acquired characters.

Weismann used this theory to explain Lamark's original examples for "use and disuse", such as the tendency to have degenerate wings and stronger feet in domesticated waterfowl.

The idea that germline cells contain information that passes to each generation unaffected by experience and independent of the somatic (body) cells, came to be referred to as the Weismann barrier, and is frequently quoted as putting a final end to the theory of Lamarck and the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

He stated that "901 young were produced by five generations of artificially mutilated parents, and yet there was not a single example of a rudimentary tail or of any other abnormality in this organ.

None of these claims, he said, were backed up by reliable evidence that the parent had in fact been mutilated, leaving the perfectly plausible possibility that the modified offspring were the result of a mutated gene.