Australia in the Vietnam War

Although initially enjoying broad support due to concerns about the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, an increasingly influential anti-war movement developed, particularly in response to the government's imposition of conscription.

[5] In 1954, after the defeat of the French Union at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, the Geneva Accords of July 1954 led to the splitting of the country geographically, along the 17th parallel north of latitude: the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) (recognised by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China) ruling the north, and the State of Vietnam (SoV) (recognised by the non-communist world) ruling the south.

[13] Between 1962 and 1972, Australia committed almost 60,000 personnel to Vietnam, including ground troops, naval forces and air assets, and contributed significant amounts of materiel to the war effort.

According to historian Paul Ham, the US Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, "freely admitted to the ANZUS meeting in Canberra in May 1962, that the US armed forces knew little about jungle warfare".

The Australian military assistance was to be in jungle warfare training, and the Team comprised highly qualified and experienced officers and NCOs, led by Colonel Ted Serong, many with previous experience from the Malayan Emergency.

For example, when Serong expressed doubt about the value of the Strategic Hamlet Program at a US Counter Insurgency Group meeting in Washington on 23 May 1963, he drew a "violent challenge" from US Marine General Victor "Brute" Krulak.

[40] Female members of the Army and RAAF nursing services were present in Vietnam from the outset and, as the force grew, the medical capability was expanded by the establishment of the 1st Australian Field Hospital at Vũng Tàu on 1 April 1968.

The battle had considerable tactical implications as well, being significant in allowing the Australians to gain dominance over Phước Tuy Province and, although there were other large-scale encounters in later years, 1 ATF was not fundamentally challenged again.

[42] Regardless, during February 1967, 1 ATF sustained its heaviest casualties in the war to that point, losing 16 men killed and 55 wounded in a single week, the bulk of them during Operation Bribie.

[43] Such losses underscored the need for a third battalion, and the requirement for tanks to support the infantry, a realisation which challenged the conventional wisdom of Australian counter-revolutionary warfare doctrine, which had previously allotted only a minor role to armour.

[44] To Brigadier Stuart Graham, the 1 ATF commander, Operation Bribie confirmed the need to establish a physical barrier, to deny the VC freedom of movement and thereby regain the initiative.

The communist Tet Offensive began on 30 January 1968 with the aim of inciting a general uprising, simultaneously engulfing population centres across South Vietnam.

In response, 1 ATF was deployed along likely infiltration routes to defend the vital Biên Hòa–Long Binh complex northeast of Saigon, as part of Operation Coburg between January and March.

[52] Tet had a similar effect on Australian public opinion, and caused growing uncertainty in the government about the determination of the United States to remain militarily involved in Southeast Asia.

[58] Later in June 1969, 5 RAR fought one of the last large-scale actions of the Australian involvement in the war, during the Battle of Binh Ba, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north of Nui Dat in Phước Tuy Province.

The battle differed from the unusual Australian experience, because it involved infantry and armour in close-quarter house-to-house fighting against a combined PAVN/VC force, through the village of Binh Ba.

A few were involved in the controversial Phoenix Program, run by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which was designed to target the VC infrastructure through infiltration, arrest and assassination.

"[72] Another perspective on Australian operations was provided by David Hackworth: "The Aussies used squads to make contact... and brought in reinforcements to do the killing; they planned in the belief that a platoon on the battlefield could do anything.

[76] Historians Andrew Ross, Robert Hall, and Amy Griffin, on the other hand make the point that Australian forces more often than not defeated the PAVN/VC whenever they met them, nine times out of ten.

[77] Meanwhile, although the bulk of Australian military resources in Vietnam were devoted to operations against the PAVN/VC forces, a civic action program was also undertaken to assist the local population and government authorities in Phước Tuy.

[78] Australian forces had first undertaken some civic action projects in 1965 while 1 RAR was operating in Biên Hòa, and similar work was started in Phước Tuy following the deployment of 1 ATF in 1966.

[80] The program continued until 1 ATF's withdrawal in 1971, and although it may have succeeded in generating goodwill towards Australian forces, it largely failed to increase support for the South Vietnamese government in the province.

[63] Meanwhile, the AATTV had been further expanded, and a Jungle Warfare Training Centre was established in Phước Tuy Province first at Nui Dat then relocated to Van Kiep.

[2] The Battle of Long Khánh on 6–7 June 1971 took place during one of the last major joint US-Australian operations, and resulted in three Australians killed and six wounded during heavy fighting in which an RAAF UH-1H Iroqouis was shot down.

[98] In March 1975 the Australian Government dispatched RAAF transport aircraft to South Vietnam to provide humanitarian assistance to refugees fleeing the North Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh Campaign.

[100] Whitlam later refused to accept South Vietnamese refugees following the fall of Saigon in April 1975, including Australian embassy staff who were later sent to re-education camps by the communists.

[106] The centre-left ALP became more sympathetic to the communists and Calwell stridently denounced South Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ as a "fascist dictator" and a "butcher" ahead of his 1967 visit[107]—at the time Ky was the chief of the Republic of Vietnam Air Force and headed a military junta.

[110] Growing public uneasiness about the death toll was fuelled by a series of highly publicised arrests of conscientious objectors, and exacerbated by revelations of atrocities committed against Vietnamese civilians, leading to a rapid increase in domestic opposition to the war between 1967 and 1970.

[125] Regardless, the "imperative to deploy forces overseas" remained a feature of Australian strategic behaviour in the post-Vietnam era,[126] while the US alliance has continued to be a fundamental aspect of its foreign policy into the early 21st century.

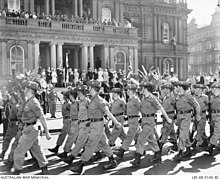

[130] Note that all the cultural items above appeared prior to 1987, the year of the "Welcome Home" parade in Sydney[122] and formed part of the process of acceptance back into the Australian community of Vietnam veterans.