Australopithecus

The genera Homo (which includes modern humans), Paranthropus, and Kenyanthropus evolved from some Australopithecus species.

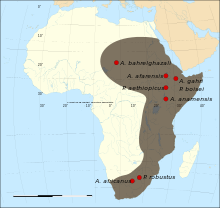

Australopithecus fossils become more widely dispersed throughout eastern and southern Africa (the Chadian A. bahrelghazali indicates that the genus was much more widespread than the fossil record suggests), before eventually becoming extinct 1.9 million years ago (or 1.2 to 0.6 million years ago if Paranthropus is included).

[13] Australopithecus possessed two of the three duplicated genes derived from SRGAP2 roughly 3.4 and 2.4 million years ago (SRGAP2B and SRGAP2C), the second of which contributed to the increase in number and migration of neurons in the human brain.

The fossil skull was from a three-year-old bipedal primate (nicknamed Taung Child) that he named Australopithecus africanus.

Dart realised that the fossil contained a number of humanoid features, and so he came to the conclusion that this was an early human ancestor.

[17] Later, Scottish paleontologist Robert Broom and Dart set out to search for more early hominin specimens, and several more A. africanus remains from various sites.

[18] The first australopithecine fossil discovered in eastern Africa was an A. boisei skull excavated by Mary Leakey in 1959 in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.

Other fossil remains found in the same cave in 2008 were named Australopithecus sediba, which lived 1.9 million years ago.

[7] On the basis of craniodental evidence, Strait and Grine (2004) suggest that A. anamensis and A. garhi should be assigned to new genera.

[37] Australopiths shared several traits with modern apes and humans, and were widespread throughout Eastern and Northern Africa by 3.5 million years ago (mya).

The earliest evidence of fundamentally bipedal hominins is a (3.6 mya) fossil trackway in Laetoli, Tanzania, which bears a remarkable similarity to those of modern humans.

[38] According to the Chimpanzee Genome Project, the human–chimpanzee last common ancestor existed about five to six million years ago, assuming a constant rate of mutation.

[44] Furthermore, thermoregulatory models suggest that australopiths were fully hair covered, more like chimpanzees and bonobos, and unlike humans.

The advantages of bipedalism were that it left the hands free to grasp objects (e.g., carry food and young), and allowed the eyes to look over tall grasses for possible food sources or predators, but it is also argued that these advantages were not significant enough to cause the emergence of bipedalism.

[citation needed] Earlier fossils, such as Orrorin tugenensis, indicate bipedalism around six million years ago, around the time of the split between humans and chimpanzees indicated by genetic studies.

[50] Australopithecus species are thought to have eaten mainly fruit, vegetables, and tubers, and perhaps easy-to-catch animals such as small lizards.

[50] In 1992, trace-element studies of the strontium/calcium ratios in robust australopith fossils suggested the possibility of animal consumption, as they did in 1994 using stable carbon isotopic analysis.

[54] In 2005, fossil animal bones with butchery marks dating to 2.6 million years old were found at the site of Gona, Ethiopia.

[59][60] In a 1979 preliminary microwear study of Australopithecus fossil teeth, anthropologist Alan Walker theorized that robust australopiths ate predominantly fruit (frugivory).

[68] In 2010, cut marks dating to 3.4 mya on a bovid leg were found at the Dikaka site, which were at first attributed to butchery by A. afarensis,[69] but because the fossil came from a sandstone unit (and were modified by abrasive sand and gravel particles during the fossilisation process), the attribution to butchery is dubious.