Paranthropus

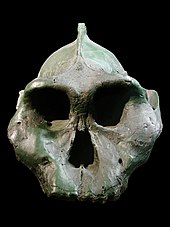

Paranthropus is characterised by robust skulls, with a prominent gorilla-like sagittal crest along the midline—which suggest strong chewing muscles—and broad, herbivorous teeth used for grinding.

Typically, Paranthropus species were generalist feeders, but while P. robustus was likely an omnivore, P. boisei seems to have been herbivorous, possibly preferring abundant bulbotubers.

[2] The type specimen, a male braincase, TM 1517, was discovered by schoolboy Gert Terblanche at the Kromdraai fossil site, about 70 km (43 mi) southwest of Pretoria, South Africa.

[3] In 1948, at Swartkrans Cave, in about the same vicinity as Kromdraai, Broom and South African palaeontologist John Talbot Robinson described P. crassidens based on a subadult jaw, SK 6.

The name derives from "Zinj", an ancient Arabic word for the coast of East Africa, and "boisei", referring to their financial benefactor Charles Watson Boise.

[8] It is debated whether the wide range of variation in jaw size indicates simply sexual dimorphism or a grounds for identifying a new species.

[12] In 1968, French palaeontologists Camille Arambourg and Yves Coppens described "Paraustralopithecus aethiopicus" based on a toothless mandible from the Shungura Formation, Ethiopia (Omo 18).

[19] Nonetheless, in 2018, independent researcher Johan Nygren recommended moving it to Paranthropus based on dental and presumed dietary similarity.

[20] In 1951, American anthropologists Sherwood Washburn and Bruce D. Patterson were the first to suggest that Paranthropus should be considered a junior synonym of Australopithecus as the former was only known from fragmentary remains at the time, and dental differences were too minute to serve as justification.

The argument rests upon whether the genus is monophyletic—is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants—and the argument against monophyly (that the genus is paraphyletic) says that P. robustus and P. boisei evolved similar gorilla-like heads independently of each other by coincidence (convergent evolution), as chewing adaptations in hominins evolve very rapidly and multiple times at various points in the family tree (homoplasy).

[24] P. aethiopicus is the earliest member of the genus, with the oldest remains, from the Ethiopian Omo Kibish Formation, dated to 2.6 mya at the end of the Pliocene.

This may have occurred during a drying trend 2.8–2.5 mya in the Great Rift Valley, which caused the retreat of woodland environments in favor of open savanna, with forests growing only along rivers and lakes.

[31] Evolutionary tree according to a 2019 study:[31] Chimpanzee Ardipithecus A. afarensis P. aethiopicus P. boisei P. robustus A. africanus H. floresiensis A. sediba H. habilis Other Homo Paranthropus had a massively built, tall and flat skull, with a prominent gorilla-like sagittal crest along the midline which anchored large temporalis muscles used in chewing.

[16][33][34] They had large molars with a relatively thick tooth enamel coating (post-canine megadontia),[35] and comparatively small incisors (similar in size to modern humans),[36] possibly adaptations to processing abrasive foods.

[40] The notably thick palate was once thought to have been an adaptation to resist a high bite force, but is better explained as a byproduct of facial lengthening and nasal anatomy.

[52] P. robustus sites are oddly dominated by small adults, which could be explained as heightened predation or mortality of the larger males of a group.

However, since circular holes in enamel coverage are uniform in size, only present on the molar teeth, and have the same severity across individuals, the PEH may have been a genetic condition.

A molar from Drimolen, South Africa, showed a cavity on the tooth root, a rare occurrence in fossil great apes.

Its powerful jaws allowed it to consume a wide variety of different plants,[38][64] though it may have largely preferred nutrient-rich bulbotubers as these are known to thrive in the well-watered woodlands it is thought to have inhabited.

Dentin exposure on juvenile teeth could indicate early weaning, or a more abrasive diet than adults which wore away the cementum and enamel coatings, or both.

[71][72] Paranthropus had pronounced sexual dimorphism, with males notably larger than females, which is commonly correlated with a male-dominated polygamous society.

Males did not seem to have ventured very far from the valley, which could either indicate small home ranges, or that they preferred dolomitic landscapes due to perhaps cave abundance or factors related to vegetation growth.

[71] Dental development seems to have followed about the same timeframe as it does in modern humans and most other hominins, but, since Paranthropus molars are markedly larger, rate of tooth eruption would have been accelerated.

[11][74] Their life history may have mirrored that of gorillas as they have the same brain volume,[75] which (depending on the subspecies) reach physical maturity from 12–18 years and have birthing intervals of 40–70 months.

[52][69] P. boisei, known from the Great Rift Valley, may have typically inhabited wetlands along lakes and rivers, wooded or arid shrublands, and semiarid woodlands,[64] though their presence in the savanna-dominated Malawian Chiwondo Beds implies they could tolerate a range of habitats.

[79] The Cradle of Humankind, the only area P. robustus is known from, was mainly dominated by the springbok Antidorcas recki, but other antelope, giraffes and elephants were also seemingly abundant megafauna.

[80] The left foot of a P. boisei specimen (though perhaps actually belonging to H. habilis) from Olduvai Gorge seems to have been bitten off by a crocodile,[81] possibly Crocodylus anthropophagus,[82] and another's leg shows evidence of leopard predation.

[81] Other likely Olduvan predators of great apes include the hunting hyena Chasmaporthetes nitidula, and the sabertoothed cats Dinofelis and Megantereon.

[72] It was once thought that Paranthropus had become a specialist feeder, and were inferior to the more adaptable tool-producing Homo, leading to their extinction, but this has been called into question.

[43] P. boisei may have died out due to an arid trend starting 1.45 mya, causing the retreat of woodlands, and more competition with savanna baboons and Homo for alternative food resources.