Automatic lathe

The 'chucker' part of the name comes from the workpieces being discrete blanks, held in a bin called a "magazine", and each one takes a turn at being chucked and machined.

(This is analogous to the way that each round of ammunition in the magazine of a semi-automatic pistol gets its turn at being chambered.)

Screw machines, being the class of automatic lathes for small- to medium-sized parts, are used in the high-volume manufacture of a vast variety of turned components.

During the Swiss screw machining process, the workpiece is supported with a guide bushing, near the cutting tool.

[5] Speaking with reference to the normal definition of the term screw machine, all screw machines are fully automated, whether mechanically (via cams) or by CNC, which means that once they are set up and started, they continue running and producing parts with little human intervention.

Any use of the term prior to the 1840s, if it occurred, would have referred ad hoc to any machine tool used to produce screws.

Within 15 years, the entire part-cutting cycle had been mechanically automated, and machines of the 1860 type were retronymously called semi-automatic.

(Brown & Sharpe continued to call some of their hand-operated turret lathe models "screw machines", but most machinists reserved the term for automatics.)

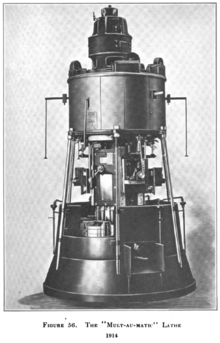

Well-known brands of such machines have included National-Acme, Hardinge, New Britain, New Britain-Gridley, Acme-Gridley, Davenport, Bullard Mult-Au-Matic (a vertical multispindle variant), and Thomas Ryder and Son.

They are limited in their economic niches to high-volume production of large parts, which tends to occur only at relatively few companies (compared to smaller work that may be done by small businesses).

This is because the few companies that have them tend to be forced to continually adapt to the latest state of the art (today all CNC) to compete and survive.

Unlike with "Grandpa's South Bend lathe" or "Dad's old Bridgeport knee mill", virtually no one can afford to keep and use them for sentimental reasons alone.

However, they are still commonly in operation, and for high-volume production of turned components it is still often true that nothing is as cost-efficient as a mechanical screw machine.

The CNC turning center most appropriately fits in the mid-range of production, replacing the turret lathe.

However, it is often possible to produce a single component with a CNC turning center more quickly than can be done with an engine lathe.

To some extent too, the CNC turning center has stepped into the region traditionally occupied by the (mechanical) screw machine.

Businesses relying on cam-op machines are still competing even in today's CNC-filled environment; they just need to be vigilant and smart about keeping it that way.

This lets shops with certain mixes of work derive competitive advantage from the lower cost compared with all-CNC machines.

Unlike on a lathe, single-point threading is rarely if ever performed; it is too time-consuming for the short cycle times that are typical of screw machines.

The most common form made this way is a hexagonal socket in the end of a cap screw.

Thus the discussion below begins with a simple overview of screw making in prior centuries, and how it evolved into 19th-, 20th-, and 21st-century practice.

Various sparks of inventive power during the Middle Ages and Renaissance combined some of these elements into screw-making machines that presaged the industrial era to follow.

For example, various medieval inventors whose names are lost to history clearly worked on the problem, as shown by Wolfegg Castle's Medieval Housebook (written circa 1475–1490),[8] and Leonardo da Vinci and Jacques Besson left us with drawings of screw-cutting machines from the 1500s;[8] not all of these designs are known to have been built, but clearly similar machines were a reality during Besson's lifetime.

Screw-cutting lathes fed into the just-dawning evolution of modern machine shop practice, whereas the wood-screw-making machines fed into the just-dawning evolution of the modern hardware industry, that is, the concept of one factory supplying the needs of thousands of customers, who consumed screws in growing quantities for carpentry, cabinet making, and other trades, but did not make the hardware themselves (purchasing it instead from capital-intensive specialist makers for lower unit cost than they could achieve on their own).

Meanwhile, on the wood-screw side, hardware manufacturers had developed for their own in-house use the first fully automatic [mechanically automated] special-purpose machine tools for the making of screws.

Single-pointing was forgone in favor of die head cutting for such medium- and high-volume repetitive production.

Then, in the 1870s, the turret lathe's part-cutting cycle (sequence of movements) was automated by being put under cam control, in a way very similar to how music boxes and player pianos can play a tune automatically.

The technological developments in America and Switzerland flowed rapidly into other industrialized countries (via routes such as machine tool exports; trade journal articles and advertisements; trade shows, from world's fairs to regional events; and the turnover and emigration of engineers, setup hands, and operators).