Axiom of choice

The axiom of choice was formulated in 1904 by Ernst Zermelo in order to formalize his proof of the well-ordering theorem.

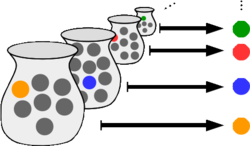

But no definite choice function is known for the collection of all non-empty subsets of the real numbers.

[3] Although originally controversial, the axiom of choice is now used without reservation by most mathematicians,[4] and is included in the standard form of axiomatic set theory, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC).

One motivation for this is that a number of generally accepted mathematical results, such as Tychonoff's theorem, require the axiom of choice for their proofs.

One variation avoids the use of choice functions by, in effect, replacing each choice function with its range: This can be formalized in first-order logic as: Note that P ∨ Q ∨ R is logically equivalent to (¬P ∧ ¬Q) → R. In English, this first-order sentence reads: This guarantees for any partition of a set X the existence of a subset C of X containing exactly one element from each part of the partition.

However, that particular case is a theorem of the Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory without the axiom of choice (ZF); it is easily proved by the principle of finite induction.

For example, suppose that each member of the collection X is a nonempty subset of the natural numbers.

Since X is not measurable for any rotation-invariant countably additive finite measure on S, finding an algorithm to form a set from selecting a point in each orbit requires that one add the axiom of choice to our axioms of set theory.

Similarly, although a subset of the real numbers that is not Lebesgue measurable can be proved to exist using the axiom of choice, it is consistent that no such set is definable.

Another argument against the axiom of choice is that it implies the existence of objects that may seem counterintuitive.

Moreover, paradoxical consequences of the axiom of choice for the no-signaling principle in physics have recently been pointed out.

The implications of choice below, including weaker versions of the axiom itself, are listed because they are not theorems of ZF.

Such statements can be rephrased as conditional statements—for example, "If AC holds, then the decomposition in the Banach–Tarski paradox exists."

As discussed above, in the classical theory of ZFC, the axiom of choice enables nonconstructive proofs in which the existence of a type of object is proved without an explicit instance being constructed.

[16] It has been known since as early as 1922 that the axiom of choice may fail in a variant of ZF with urelements, through the technique of permutation models introduced by Abraham Fraenkel[17] and developed further by Andrzej Mostowski.

In 1938,[19] Kurt Gödel showed that the negation of the axiom of choice is not a theorem of ZF by constructing an inner model (the constructible universe) that satisfies ZFC, thus showing that ZFC is consistent if ZF itself is consistent.

He did this by constructing a much more complex model that satisfies ZF¬C (ZF with the negation of AC added as axiom) and thus showing that ZF¬C is consistent.

The assumption that ZF is consistent is harmless because adding another axiom to an already inconsistent system cannot make the situation worse.

Many theorems provable using choice are of an elegant general character: the cardinalities of any two sets are comparable, every nontrivial ring with unity has a maximal ideal, every vector space has a basis, every connected graph has a spanning tree, and every product of compact spaces is compact, among many others.

Likewise, a finite product of compact spaces can be proven to be compact without the axiom of choice, but the generalization to infinite products (Tychonoff's theorem) requires the axiom of choice.

When attempting to solve problems in this class, it makes no difference whether ZF or ZFC is employed if the only question is the existence of a proof.

In fact, Zermelo initially introduced the axiom of choice in order to formalize his proof of the well-ordering theorem.

These results might be weaker than, equivalent to, or stronger than the axiom of choice, depending on the strength of the technical foundations.

On the other hand, other foundational descriptions of category theory are considerably stronger, and an identical category-theoretic statement of choice may be stronger than the standard formulation, à la class theory, mentioned above.

Given an ordinal parameter α ≥ 1 — for every set S with Hartogs number less than ωα, S is well-orderable.

As the ordinal parameter is increased, these approximate the full axiom of choice more and more closely.

One of the most interesting aspects of the axiom of choice is the large number of places in mathematics where it shows up.

In 1906, Russell declared PP to be equivalent, but whether the partition principle implies AC is the oldest open problem in set theory,[36] and the equivalences of the other statements are similarly hard old open problems.

It is also consistent with ZF + DC that every set of reals is Lebesgue measurable, but this consistency result, due to Robert M. Solovay, cannot be proved in ZFC itself, but requires a mild large cardinal assumption (the existence of an inaccessible cardinal).

Additionally, by imposing definability conditions on sets (in the sense of descriptive set theory) one can often prove restricted versions of the axiom of choice from axioms incompatible with general choice.