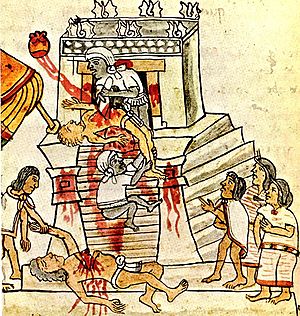

Human sacrifice in Aztec culture

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who participated in the Cortés expedition, made frequent mention of human sacrifice in his memoir True History of the Conquest of New Spain.

Since the late 1970s, excavations of the offerings in the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan, and other archaeological sites, have provided physical evidence of human sacrifice among the Mesoamerican peoples.

Even the "stage" for human sacrifice, the massive temple-pyramids, was an offering mound: crammed with the land's finest art, treasure and victims; they were then buried underneath for the deities.

The 16th-century Florentine Codex by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún reports that in one of the creation myths, Quetzalcóatl offered blood extracted from a wound in his own penis to give life to humanity.

[13] According to Diego Durán's History of the Indies of New Spain (and a few other sources that are believed to be based on the Crónica X), the flower wars were a ritual among the cities of Aztec Triple Alliance and Tlaxcala, Huexotzingo and Cholula.

[15] In addition, regular warfare included the use of long range weapons such as atlatl darts, stones, and sling shots to damage the enemy from afar.

The body parts would then be disposed of, the viscera fed to the animals in the zoo, and the bleeding head was placed on display in the tzompantli or the skull rack.

[22] Additionally, some historians argue that these numbers were inaccurate as most written account of Aztec sacrifices were made by Spanish sources to justify Spain's conquest.

[23] Nonetheless, according to Codex Telleriano-Remensis, old Aztecs who talked with the missionaries told about a much lower figure for the reconsecration of the temple, approximately 4,000 victims in total.

Michael Harner, in his 1977 article The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice, cited an estimate by Borah of the number of persons sacrificed in central Mexico in the 15th century as high as 250,000 per year, which may have been one percent of the population.

[19] Likewise, most of the earliest accounts talk of prisoners of war of diverse social status, and concur that virtually all child sacrifices were locals of noble lineage, offered by their own parents.

[18] Huitzilopochtli was the tribal deity of the Mexica and, as such, he represented the character of the Mexican people and was often identified with the sun at the zenith, and with warfare, who burned down towns and carried a fire-breathing serpent, Xiuhcoatl.

During the festival priests would march to the top of the volcano Huixachtlan and when the constellation "the fire drill" (Orion's belt) rose over the mountain, a man would be sacrificed.

[46] In the Florentine Codex, also known as General History of the Things of New Spain, Sahagún wrote: According to the accounts of some, they assembled the children whom they slew in the first month, buying them from their mothers.

Prior to death and dismemberment the victim's skin would be removed and worn by individuals who traveled throughout the city fighting battles and collecting gifts from the citizens.

Rather than showing a preoccupation with debt repayment, they emphasize the mythological narratives that resulted in human sacrifices, and often underscore the political legitimacy of the Aztec state.

[21] For instance, the Coyolxauhqui stone found at the foot of the Templo Mayor commemorates the mythic slaying of Huitzilopochli's sister for the matricide of Coatlicue; it also, as Cecelia Kline has pointed out, "served to warn potential enemies of their certain fate should they try to obstruct the state's military ambitions".

He said, When he reached said tower the Captain asked him why such deeds were committed there and the Indian answered that it was done as a kind of sacrifice and gave to understand that the victims were beheaded on the wide stone; that the blood was poured into the vase and that the heart was taken out of the breast and burnt and offered to the said idol.

Arriving at Cholula, they find "cages of stout wooden bars ... full of men and boys who were being fattened for the sacrifice at which their flesh would be eaten".

[59] When the conquistadors reached Tenochtitlan, Díaz described the sacrifices at the Great Pyramid: They strike open the wretched Indian's chest with flint knives and hastily tear out the palpitating heart which, with the blood, they present to the idols ...

[60]According to Bernal Díaz, the chiefs of the surrounding towns, for example Cempoala, would complain on numerous occasions to Cortés about the perennial need to supply the Aztecs with victims for human sacrifice.

According to Bernal Díaz: Every day we saw sacrificed before us three, four or five Indians whose hearts were offered to the idols and their blood plastered on the walls, and their feet, arms and legs of the victims were cut off and eaten, just as in our country we eat beef bought from the butchers.

[64]The Anonymous Conquistador was an unknown travel companion of Cortés who wrote Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan which details Aztec sacrifices.

At this point the chief priest of the temple takes it, and anoints the mouth of the principal idol with the blood; then filling his hand with it he flings it towards the sun, or towards some star, if it be night.

[68] Indentations in the rib cage of a set of remains reveal the act of accessing the heart through the abdominal cavity, which correctly follows images from the codices in the pictorial representation of sacrifice.

He claimed that very high population pressure and an emphasis on maize agriculture, without domesticated herbivores, led to a deficiency of essential amino acids amongst the Aztecs.

Victims usually died in the "center stage" amid the splendor of dancing troupes, percussion orchestras, elaborate costumes and decorations, carpets of flowers, crowds of thousands of commoners, and all the assembled elite.

[19] Particularly the young man who was indoctrinated for a year to submit himself to Tezcatlipoca's temple was the Aztec equivalent of a celebrity, being greatly revered and adored to the point of people "kissing the ground" when he passed by.

[73] Posthumously, their remains were treated as actual relics of the gods which explains why victims' skulls, bones and skin were often painted, bleached, stored and displayed, or else used as ritual masks and oracles.

For example, Diego Duran's informants told him that whoever wore the skin of the victim who had portrayed god Xipe (Our Lord the Flayed One) felt he was wearing a holy relic.