Aztec codex

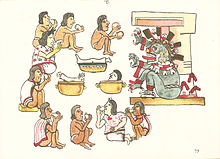

[1] Before the start of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Mexica and their neighbors in and around the Valley of Mexico relied on painted books and records to document many aspects of their lives.

[2] According to the testimony of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Moctezuma had a library full of such books, known as amatl, or amoxtli, kept by a calpixqui or nobleman in his palace, some of them dealing with tribute.

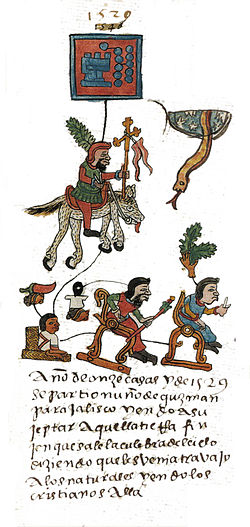

[3] After the conquest of Tenochtitlan, indigenous nations continued to produce painted manuscripts, and the Spaniards came to accept and rely on them as valid and potentially important records.

The native tradition of pictorial documentation and expression continued strongly in the Valley of Mexico several generations after the arrival of Europeans, its latest examples reaching into the early seventeenth century.

This has historical reasons, for according to Codex Xolotl and historians like Ixtlilxochitl, the art of tlacuilolli or manuscript painting was introduced to the Tolteca-Chichimeca ancestors of the Tetzcocans by the Tlaoilolaques and Chimalpanecas, two Toltec tribes from the lands of the Mixtecs.

Regarding local schools within the Aztec pictorial style, Robertson was the first to distinguish three of them: A large number of prehispanic and colonial indigenous texts have been destroyed or lost over time.

For example, besides the testimony of Bernal Díaz quoted above, the conquistador Juan Cano de Saavedra describes some of the books to be found at the library of Moctezuma, dealing with religion, genealogies, government, and geography, lamenting their destruction at the hands of the Spaniards, for such books were essential for the government and policy of indigenous nations.

[12] Further loss was caused by Catholic priests, who destroyed many of the surviving manuscripts during the early colonial period, burning them because they considered them idolatrous.

A major publication project by scholars of Mesoamerican ethnohistory was brought to fruition in the 1970s: volume 14 of the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources: Part Three is devoted to Middle American pictorial manuscripts, including numerous reproductions of single pages of important pictorials.

They follow a standard format, usually written in alphabetic Nahuatl with pictorial content concerning a meeting of a given indigenous pueblo's leadership and their marking out the boundaries of the municipality.

[19] Another mixed alphabetic and pictorial source for Mesoamerican ethnohistory is the late sixteenth-century Relaciones geográficas, with information on individual indigenous settlements in colonial Mexico, created on the orders of the Spanish crown.

[25] The project resulted in twelve books, bound into three volumes, of bilingual Nahuatl/Spanish alphabetic text, with illustrations by native artists; the Nahuatl has been translated into English.

[26] Also important are the works of Dominican Diego Durán, who drew on indigenous pictorials and living informants to create illustrated texts on history and religion.