Aztec society

But, while they were impacted by various sources, they developed their own distinct social groupings, political structures, traditions, and leisure activities.

Under the influence of classic Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Teotihuacanos, the Maya, the Totonacs and the Huastecs the proto-Aztecs became sedentary agriculturalists and achieved the same levels of technology as their neighboring peoples.

For example, the pochteca, long-distance traders, were considered commoners yet at the same time held a number of privileges comparable to those of the lesser nobility.

The exact nature of the calpulli is not completely understood and it has been variously described as a kind of clan, a town, a ward, a parish or an agriculture based cooperative.

He provided the calpulli members with lands for cultivation (calpullālli) or with access to non-agricultural occupations in exchange for tribute and loyalty.

Aztecs married at a later age, during their late teens and early twenties, whereas in Mayan culture it was not unusual for marriages to be arranged by parents for a son and daughter who were still children.

[10] James Lockhart, who specializes in the historical description of the Nahua, said Aztec society was characterized by a "tendency to create larger wholes by the aggregation of parts that remain relatively separate and self-contained brought together by their common function and similarity".

Some alliances were short-lived and others were long-term relationships wherein a group of altepetl would converge to form what could almost be considered a single political entity.

[12] Another is the so-called Aztec Triple Alliance between Tlacopan, Texcoco and Tenochtitlan which was originally formed to end the dominance of the altepetl Azcapotzalco.

Recent studies have countered the claim that the Aztec Empire ran the triple alliance by suggesting that Tenochtitlan was actually the dominant altepetl all along.

Furthermore, each Altepetl usually produced some form of unique trade good, meaning there were significant merchant and artisan classes.

In the swampy regions along Lake Xochimilco, the Aztecs implemented a unique method of crop cultivation, chinampas.

Chinampas, areas of raised land in a body of water, were created from alternating layers of mud from the bottom of the lake and plant matter/other vegetation.

They rose approximately 1 meter above the surface of the water, and were separated by narrow canals, which allowed farmers to move between them by canoe.

General laborers could be slaves, menial workers, or farm hands, while specialists were responsible for things like choosing the most successful seeds and crop rotations.

[citation needed] The markets, which were located in the center of many communities, were well organized and diverse in goods, as noted by the Spanish conquistadors upon their arrival.

[citation needed] The regional merchants, known as tlacuilo, would barter utilitarian items and food, which included gold, silver, and other precious stones, cloth and cotton, animal skins, both agriculture and wild game, and woodwork.

With no domestic animals as an effective way to transport goods, the local markets were an essential part of Aztec commerce.

Due to the success of the pochteca, many of the merchants became as wealthy as the noble class, but were obligated to hide this wealth from the public.

These people were often referred to as the richest of merchants, as they played a central role in capturing the slaves used for sacrificial victims.

[citation needed] The third group of long-distance traders was the tencunenenque, who worked for the rulers by carrying out personal trade.

[citation needed] All trade throughout the Aztec Empire was regulated by officers who patrolled the markets to ensure that the buyers were not being cheated by the merchants.

[citation needed] The Mexica, the founders and dominant group of the Aztec Empire, were one of the first people in the world to have mandatory education for nearly all children, regardless of gender, rank, or station.

[citation needed] There were two types of schools: the telpochcalli, for practical and military studies, and the calmecac, for advanced learning in writing, astronomy, statesmanship, theology, and other areas.

Aztec teachers (tlamatimine) propounded a spartan regime of education – cold baths in the morning, hard work, physical punishment, bleeding with maguey thorns and endurance tests – with the purpose of forming a stoical people.

[citation needed] There is contradictory information about whether calmecac was reserved for the sons and daughters of the pillis; some accounts said they could choose where to study.

[citation needed] It is possible that the common people preferred the telpochcalli, because a warrior could advance more readily by his military abilities; becoming a priest or a tlacuilo was not a way to rise rapidly from a low station.

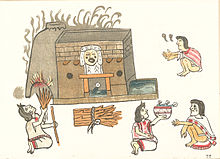

Bathing was not restricted to the elite, but was practised by all people; the chronicler Tomás López Medel wrote after a journey to Central America that "Bathing and the custom of washing oneself is so quotidian (common) amongst the Indians, both of cold and hot lands, as is eating, and this is done in fountains and rivers and other water to which they have access, without anything other than pure water..."[19] The Mesoamerican bath, known as temazcal, from the Nahuatl word temazcalli, a compound of temaz ("steam") and calli ("house"), consists of a room, often in the form of a small dome, with an exterior firebox known as texictle (teʃict͜ɬe) that heats a small portion of the room's wall made of volcanic rocks; after this wall has been heated, water is poured on it to produce steam, an action known as tlasas.

As the steam accumulates in the upper part of the room a person in charge uses a bough to direct the steam to the bathers who are lying on the ground, with which he later gives them a massage, then the bathers scrub themselves with a small flat river stone and finally the person in charge introduces buckets with water with soap and grass used to rinse.

[20] (search return) specifically: Kathleen Kuiper - Pre-Columbian America: Empires of the New World The Rosen Publishing Group, 2010 ISBN 161530150X