Key signature

The initial key signature in a piece is placed immediately after the clef at the beginning of the first line.

In a key signature, a sharp or flat symbol on a line or space of the staff indicates that the note represented by that line or space is to be played a semitone higher (sharp) or lower (flat) than it would otherwise be played.

Each symbol applies to comparable notes in all octaves—for example, a flat on the fourth space of the treble staff (as in the diagram) indicates that all notes notated as Es are played as E-flats, including those on the bottom line of the staff.

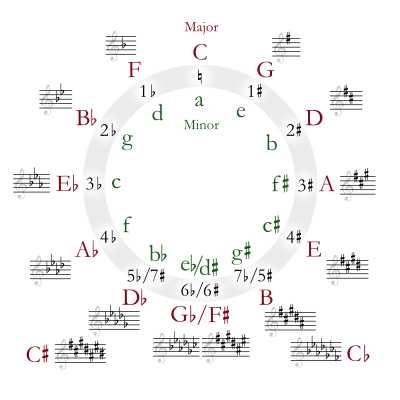

In standard music notation, the order in which sharps or flats appear in key signatures is uniform, following the circle of fifths: F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, and B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭.

Musicians can identify the key by the number of sharps or flats shown, since they always appear in the same order.

A key signature with one sharp must show F-sharp,[3] which indicates G major or E minor.

There can be exceptions to this, especially in 20th-century music, if a piece uses an unorthodox or synthetic scale and an invented key signature to reflect that.

Key signatures of this kind can be found in the music of Béla Bartók, for example.

Percussion instruments with indeterminate pitch will not show a key signature, and timpani parts are sometimes written without a key signature (early timpani parts were sometimes notated with the high drum as "C" and the low drum a fourth lower as "G", with actual pitches indicated at the beginning of the music, e.g., "timpani in D–A").

The order in which sharps or flats appear in key signatures is illustrated in the diagram of the circle of fifths.

This pattern continues, raising the seventh scale degree of each successive key.

This is strictly a function of notation—the seventh scale degree is still being raised by a semitone compared to the previous key in the sequence.

The key signatures with seven flats and seven sharps are usually notated in their enharmonic equivalents.

In some scores by Debussy the barline is placed after the naturals but before the new key signature.

This section could be written using the enharmonically equivalent key signature of A-flat major instead.

Claude Debussy's Suite bergamasque does this: in the third movement "Clair de lune" the key shifts from D-flat major to D-flat minor (eight flats) for a few measures but the passage is notated in C-sharp minor (four sharps); the same happens in the final movement, "Passepied", in which a G-sharp major section is written as A-flat major.

The final pages of John Foulds' A World Requiem are written in G♯ major (with F in the key signature), No.

18 of Anton Reicha's Practische Beispiele is written in B# major, and the third movement of Victor Ewald's Brass Quintet Op.

The sharps or flats needed to produce a diatonic scale in diatonic or tonal music can be shown as a key signature at the beginning of a section of music instead of showing accidentals on individual notes.

The Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 538 by Bach has a key signature with no sharps or flats, indicating that it may be in D, in Dorian mode, but the B♭s indicated with accidentals make the music in D minor.

20th century composers such as Bartók and Rzewski (see below) experimented with non-diatonic key signatures.

An example is Bartók's Piano Sonata, which has no fixed key and is highly chromatic.