B movies (Hollywood Golden Age)

As the Hollywood studios made the transition to sound film in the late 1920s, many independent exhibitors began adopting a new programming format: the double feature.

The double feature was the predominant presentation model at American theaters throughout the Golden Age, and B movies constituted the majority of Hollywood production during the period.

[2] According to historian Thomas Schatz, "These low-grade westerns, melodramas, and action pictures...underwent a disciplined production and marketing process," in contrast to the Jewels, which were not as strictly governed by studio policies.

[9] Indicating the breadth of the budgetary range at a single studio, in 1921, when the average cost of a Hollywood feature was around $60,000,[10] Universal spent approximately $34,000 on The Way Back, a five-reeler, and over $1 million on Foolish Wives, a top-of-the-line Super Jewel.

[12] By 1927–28, at the end of the silent era, the production cost of an average feature from Hollywood's major film studios had soared, ranging from $190,000 at Fox to $275,000 at MGM.

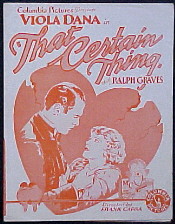

"[14] Studios in the minor leagues of the industry, such as Columbia Pictures and Film Booking Offices of America (FBO), focused on low-budget productions; most of their movies, with relatively short running times, targeted theaters that had to economize on rental and operating costs—particularly those in small towns and so-called neighborhood venues, or "nabes," in big cities.

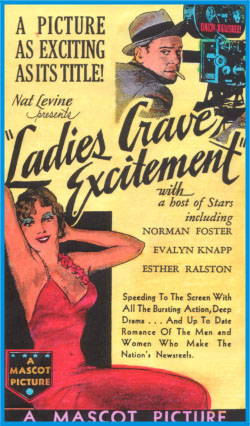

Even smaller outfits—the sort typical of Hollywood's so-called Poverty Row—made films whose production costs might run as low as $3,000, seeking a profit through whatever bookings they could pick up in the gaps left by the larger concerns.

[18] The bottom-billed movie also gave the program "balance"—the practice of pairing different sorts of features suggested to potential customers that they could count on something of interest no matter what specifically was on the bill.

Block booking increasingly became standard practice: in order to get access to a studio's attractive A pictures, many theaters were obliged to rent the company's entire output for a season.

[21] In the model that would be standard during the Golden Age, the industry's top product, its A films, would premiere at a select number of deluxe first-run metropolitan cinemas, located in U.S. cities with populations in the range of 100,000 and above.

As described by historian Edward Jay Epstein, "During the[ir] first runs, films got their reviews, garnered publicity, and generated the word of mouth that served as the principal form of advertising.

[25] As historian Brian Taves describes, "Many of the poorest theaters, such as the 'grind houses' in the larger cities, screened a continuous program emphasizing action with no specific schedule, sometimes offering six quickies for a nickel in an all-night show that changed daily.

[28] A broad range of Hollywood motion pictures occupied the B-movie category: The leading studios made not only clear-cut A and B films, but also movies classifiable as "programmers" (also "in-betweeners" or "intermediates").

Calculating in the three hundred or so films made annually by the many Poverty Row firms, approximately 75 percent of Hollywood movies from the decade, more than four thousand pictures, are classifiable as B's.

At just one major studio, Fox, B series produced by Sol Wurtzel included "Charlie Chan, Mr. Moto, Sherlock Holmes, Michael Shayne, the Cisco Kid, George O'Brien westerns [before his move to RKO], the Gambini sports films, the Roving Reporters, the Camera Daredevils, the Big Town Girls, the hotel for women, the Jones Family, the Jane Withers children's films, Jeeves, [and] the Ritz Brothers.

As with serials, however, many series were specifically intended to interest young people—some of the theaters that twin-billed part-time might run a "balanced" or entirely youth-oriented double feature as a matinee and then a single film for a more mature audience at night.

In the words of a contemporary Gallup industry report, afternoon moviegoers, "composed largely of housewives and children, want quantity for their money while the evening crowds want 'something good and not too much of it.

Reviewing the 77-minute Universal crime melodrama Rio (1939), The New York Times declared that director "John Brahm's impact on the Class B picture is producing one of the strangest sound effects in recent cinema history.

[28] A number of small Hollywood companies had folded around the turn of the decade, including the ambitious Grand National, but a new firm, Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), emerged as third in the Poverty Row hierarchy behind Republic and Monogram.

[53] In late 1946, executives at the newly merged Universal-International announced that no U-I feature would run less than seventy minutes; supposedly, all B pictures were to be discontinued, even if they were in the midst of production.

"[58] Many smaller Poverty Row firms were folding because there simply was not enough money to go around: the eight majors, with their proprietary distribution exchanges, were now "taking in around 95 percent of all domestic (U.S. and Canada) rental receipts.

[64] The leading Poverty Row firms began to broaden their scope: In 1947, Monogram established a subsidiary, Allied Artists, as a development and distribution channel for relatively expensive films, mostly from independent producers.

Lewton produced such moody, mysterious films as Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and The Body Snatcher (1945), directed by Jacques Tourneur, Robert Wise, and others who would become renowned only later in their careers or entirely in retrospect.

The movie now widely described as the first classic film noir—Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a 64-minute B—was produced at RKO, which would release many melodramatic thrillers in a similarly stylish vein during the decade.

Ten straight B noirs that year came from Poverty Row's big three: Republic (Blackmail and The Pretender), Monogram (Fall Guy, The Guilty, High Tide, and Violence), and PRC/Eagle-Lion (Bury Me Dead, Lighthouse, Whispering City, and Railroaded, another work of Mann).

RKO's representative output included the Mexican Spitfire and Lum and Abner comedy series, thrillers featuring the Saint and the Falcon, westerns starring Tim Holt, and Tarzan movies with Johnny Weissmuller.

The Courageous Dr. Christian (1940) was a standard entry in the franchise: "In the course of an hour or so of screen time, the saintly physician managed to cure an epidemic of spinal meningitis, demonstrate benevolence towards the disenfranchised, set an example for wayward youth, and calm the passions of an amorous old maid.

Republic aspired to major-league respectability while making many cheap and modestly budgeted westerns, but there was not much from the bigger studios that compared with Monogram "exploitation pictures" like juvenile delinquency exposé Where Are Your Children?

"[72] Described by critic and historian David Thomson as "one of the most fascinating talents in the worldwide labyrinth of sub-B pictures," Ulmer made films of every generic stripe.

[73] His Girls in Chains was released in May 1943, six months before Women in Bondage; by the end of the year, Ulmer had also made the teen-themed musical Jive Junction as well as Isle of Forgotten Sins, a South Seas adventure set around a brothel.