Balance wheel

It is driven by the escapement, which transforms the rotating motion of the watch gear train into impulses delivered to the balance wheel.

Each swing of the wheel (called a "tick" or "beat") allows the gear train to advance a set amount, moving the hands forward.

The combination of the mass of the balance wheel and the elasticity of the spring keep the time between each oscillation or "tick" very constant, accounting for its nearly universal use as the timekeeper in mechanical watches to the present.

From its invention in the 14th century until tuning fork and quartz movements became available in the 1960s, virtually every portable timekeeping device used some form of balance wheel.

Until the 1980s balance wheels were the timekeeping technology used in chronometers, bank vault time locks, time fuzes for munitions, alarm clocks, kitchen timers and stopwatches, but quartz technology has taken over these applications, and the main remaining use is in quality mechanical watches.

[4] During World War II, Elgin produced a very precise stopwatch for US Air Force bomber crews that ran at 40 beats per second (144,000 BPH), earning it the nickname 'Jitterbug'.

The most accurate balance wheel timepieces made were marine chronometers, which were used on ships for celestial navigation, as a precise time source to determine longitude.

It is an improved version of the foliot, an early inertial timekeeper consisting of a straight bar pivoted in the center with weights on the ends, which oscillates back and forth.

[8] Since more of its weight is located on the rim away from the axis, a balance wheel could have a larger moment of inertia than a foliot of the same size, and keep better time.

The wheel shape also had less air resistance, and its geometry partly compensated for thermal expansion error due to temperature changes.

This is why all pre-balance spring watches required fusees (or in a few cases stackfreeds) to equalize the force from the mainspring reaching the escapement, to achieve even minimal accuracy.

The idea of the balance spring was inspired by observations that springy hog bristle curbs, added to limit the rotation of the wheel, increased its accuracy.

[11][12] Robert Hooke first applied a metal spring to the balance in 1658 and Jean de Hautefeuille and Christiaan Huygens improved it to its present spiral form in 1674.

[18] The need for an accurate clock for celestial navigation during sea voyages drove many advances in balance technology in 18th century Britain and France.

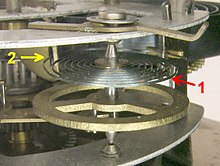

The rim was cut open at two points next to the spokes of the wheel, so it resembled an S-shape (see figure) with two circular bimetallic "arms".

The standard Earnshaw compensation balance dramatically reduced error due to temperature variations, but it didn't eliminate it.

To mitigate this problem, chronometer makers adopted various 'auxiliary compensation' schemes, which reduced error below 1 second per day.

The blocked movement causes a non-linear temperature response that could slightly better compensate the elasticity changes in the spring.

Charles Édouard Guillaume won a Nobel prize for the 1896 invention of Invar, a nickel steel alloy with very low thermal expansion, and Elinvar (from élasticité invariable, 'invariable elasticity') an alloy whose elasticity is unchanged over a wide temperature range, for balance springs.