Marine chronometer

When first developed in the 18th century, it was a major technical achievement, as accurate knowledge of the time over a long sea voyage was vital for effective navigation, lacking electronic or communications aids.

The first true chronometer was the life work of one man, John Harrison, spanning 31 years of persistent experimentation and testing that revolutionized naval (and later aerial) navigation.

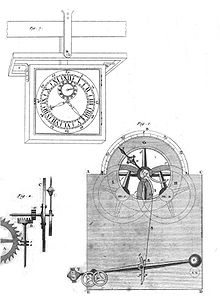

The 1713 book Physico-Theology by the English cleric and scientist William Derham includes one of the earliest theoretical descriptions of a marine chronometer.

Most people can master simpler celestial navigation procedures after a day or two of instruction and practice, even using manual calculation methods.

Christiaan Huygens, following his invention of the pendulum clock in 1656, made the first attempt at a marine chronometer in 1673 in France, under the sponsorship of Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

[9] Attempts to construct a working marine chronometer were begun by Jeremy Thacker in England in 1714, and by Henry Sully in France two years later.

[13] A French expedition under Charles-François-César Le Tellier de Montmirail performed the first measurement of longitude using marine chronometers aboard Aurore in 1767.

The new technology was initially so expensive that not all ships carried chronometers, as illustrated by the fateful last journey of the East Indiaman Arniston, shipwrecked with the loss of 372 lives.

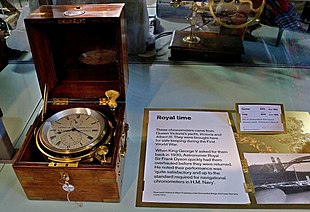

[22][23] Marine chronometer makers looked to a phalanx of astronomical observatories located in Western Europe to conduct accuracy assessments of their timepieces.

Every day, ships would anchor briefly in the River Thames at Greenwich, waiting for the ball at the observatory to drop at precisely 1pm.

In addition to setting their time before departing on a voyage, ship chronometers were also routinely checked for accuracy while at sea by carrying out lunar[26] or solar observations.

Though much less accurate (and less expensive) than the chronometer, the hack watch would be satisfactory for a short period of time after setting it (i.e., long enough to make the observations).

Around the turn of the 20th century, Swiss makers such as Ulysse Nardin made great strides toward incorporating modern production methods and using fully interchangeable parts, but it was only with the onset of World War II that the Hamilton Watch Company in the United States perfected the process of mass production, which enabled it to produce thousands of its Hamilton Model 21 and Model 22 chronometers from 1942 onwards for the branches of the United States military and merchant marine as well as other Allied forces during World War II.

[28] During the course of World War II modifications that became necessary when raw materials became scarce were applied and work was compulsory and sometimes voluntarily shared between various German manufacturers to speed up production.

The production of German unified design chronometers with their harmonized components continued until long after World War II in Germany and the Soviet Union, who confiscated the original Einheitschronometer technical drawings, and set up a production line in Moscow in 1949 that produced the first Soviet MX6 chronometers containing German made movements.

Ship’s marine chronometers are the most exact portable mechanical timepieces ever produced and in a static environment were only trumped by non-portable precision pendulum clocks for observatories.

The seafaring nations invested richly in the development of these precision instruments, as pinpointing location at sea gave a decisive naval advantage.

Without their accuracy and the accuracy of the feats of navigation that marine chronometers enabled, it is arguable that the ascendancy of the Royal Navy, and by extension that of the British Empire, might not have occurred so overwhelmingly; the formation of the empire by wars and conquests of colonies abroad took place in a period in which British vessels had reliable navigation due to the chronometer, while their Portuguese, Dutch, and French opponents did not.

[36] In 1985 the British Ministry of Defence invited bids by tender for the disposal of their mechanical Hamilton Model 21 Marine Chronometers.

At the end of the 20th century the production of mechanical marine chronometers had declined to the point where only a few were being made to special order by the First Moscow Watch Factory 'Kirov' (Poljot) in Russia, Wempe in Germany and Mercer in England.

[37] The most complete international collection of marine chronometers, including Harrison's H1 to H4, is at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, in London, UK.

At the same time, it supplies minute amounts of energy to counter tiny losses from friction, thus maintaining the momentum of the oscillating balance.

In both of these, a small detent locks the escape wheel and allows the balance to swing completely free of interference except for a brief moment at the centre of oscillation, when it is least susceptible to outside influences.

At the centre of oscillation, a roller on the balance staff momentarily displaces the detent, allowing one tooth of the escape wheel to pass.

When the oil thickens through age or temperature or dissipates through humidity or evaporation, the rate will change, sometimes dramatically as the balance motion decreases through higher friction in the escapement.

Chronometer escape wheels and passing springs are typically gold due to the metal's lower slide friction over brass and steel.

Until the end of mechanical chronometer production in the third quarter of the 20th century, makers continued to experiment with things like ball bearings and chrome-plated pivots.

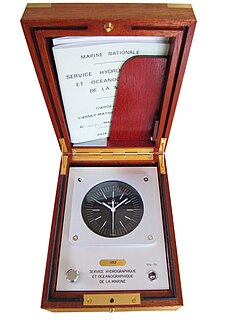

The timepieces were normally protected from the elements and kept below decks in a fixed position in a traditional box suspended in gimbals (a set of rings connected by bearings).

This keeps the chronometer isolated in a horizontal "dial up" position to counter ship inclination (rocking) movements induced timing errors on the balance wheel.

[41] Using multiple independent position fix methods without solely relying on subject-to-failure electronic systems helps the navigator detect errors.