Baltimore Steam Packet Company

Walter Lord, famed author of A Night to Remember (and whose grandfather had been the packet line's president from 1893 to 1899), mused that its reputation for excellent service was attributable to "some magical blending of the best in the North and the South, made possible by the Company's unique role in 'bridging' the two sections...the North contributed its tradition of mechanical proficiency, making the ships so reliable; while the South contributed its gracious ease".

[2] In 1947 a former Old Bay Line steamship, President Warfield, became Exodus, carrying Jewish refugees from Europe in an unsuccessful attempt to emigrate to Mandatory Palestine.

Just seven years after Robert Fulton proved the commercial viability of steam-powered ships with his North River Steamboat (more commonly known today as Clermont) in 1807, small wood-burning steamers began to ply the Chesapeake Bay.

This was especially so in North America, where journeys over vast distances of hundreds or even thousands of miles required months of hazardous, uncomfortable travel by stagecoach or wagon on rutted, unpaved trails.

[4] In this period, steamships on rivers such as the Ohio and Mississippi or large inland bodies of water such as the Great Lakes and the Chesapeake Bay offered a comfortable and relatively fast mode of transportation.

[5][Note 1] The company began overnight paddlewheel steamship passenger and freight service daily except Sundays between Baltimore and Norfolk.

Night came on, and her azure curtain gemmed with myriad stars was drawn over the expanse above.North Carolina similarly impressed a Baltimore Patriot reporter in 1852, who described the ship's dining saloon as "having imported Belgian carpets, velvet chairs with marble-topped tables, and white panelling with gilded mouldings".

[8] On February 20, 1858, the northbound steamer Louisiana collided with a sailing vessel hauling a catch of oysters, William K. Perrin, causing the sailboat to founder near the mouth of the Rappahannock River.

[10] In a case that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Haney et al. v Baltimore Steam Packet Company, Louisiana was found to be at fault.

On April 19, two days after Virginia's secession, a violently pro-Southern mob in Baltimore attacked Union soldiers en route to Washington, D.C., as the troops marched through the city's streets between railroad stations.

In that role, she was used to transport Federal troops in support of operations in North Carolina's Outer Banks, directed against the Confederate-held forts guarding Hatteras Inlet.

When hostilities commenced, Southern ports were blockaded by the Federal Navy and the Old Bay Line was unable to serve Norfolk for the duration of the war, going no further south than Old Point Comfort.

[15] As soon as the war ended in 1865, the Leary Line of New York briefly challenged the Baltimore Steam Packet Company on the Chesapeake, starting its own Baltimore-Norfolk steamship service.

Two years later, the Norfolk Journal of August 2, 1869, described the vessel as having a "gorgeous style of furniture and elegant fittings...magnificently furnished with upholstered sofas and lounges of rich red velvet...".

By the time of John Moncure Robinson's retirement as president of the company in 1893, the Old Bay Line had upgraded its fleet with propeller-driven, steel-hulled steamers equipped with modern conveniences such as electric lighting and staterooms with private baths.

Georgia introduced in 1887 was the first Old Bay Line boat to have a modern screw propeller instead of old-fashioned side paddlewheels and Alabama launched in 1893 was the company's first steel-hulled vessel.

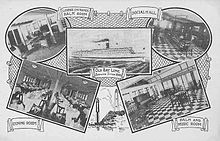

[17] The halcyon days of the 1890s were the company's heyday, under president Richard Curzon Hoffman (the grandfather of noted author Walter Lord), when the prosperous line's gleaming steamships were heavily patronized by passengers enjoying the well-appointed staterooms and Chesapeake Bay culinary delights while dining to the accompaniment of live music.

[18] Baltimore-native John Roberts Sherwood, who had joined the Old Bay Line as a 22-year-old engineer in 1868 and became president in 1907, retired in October 1918 after 49 years with the company.

The Baltimore Sun extolled Sherwood's distinguished half-century of service to the steamer line when he retired, noting approvingly that his oft-expressed philosophy was, "Stand up for your home city wherever you may go.

[2] By the Depression-ravaged 1930s, however, the Old Bay Line became one of the first inland steamship companies to promote the carriage of automobiles as a means of filling its ships' empty cargo holds.

In 1939, State of Virginia was converted to oil burning and all three ships were equipped with radio direction finders and ship-to-shore telephones.

[22] Robert E. Dunn was named president of the Old Bay Line in 1941, remaining at the helm of the company to the end of service in 1962.

[21] After World War II, the line promoted its automobile service to Florida-bound motorists, advertising the elimination of 230 miles (370 km) of driving by taking the family car on an overnight cruise down the Chesapeake to Virginia, while enjoying a sumptuous dinner and relaxing stateroom aboard an Old Bay Line steamer instead of a roadside motel.

[21] The old President Warfield was eventually acquired in early 1947 by Mossad Le'aliyah Bet, a Jewish organization helping Holocaust survivors illegally reach Mandatory Palestine, then under British rule.

[24] Various travel writers in the 1950s extolled the pleasures of the nightly cruises and meals on the Old Bay Line's antique steamers.

By the mid-1950s, however, improved highways and the increase in air travel meant that the Old Bay Line's 12-hour transit time between Baltimore and Norfolk was a comparatively slow means of transportation.

The Sunday travel section of The New York Times in 1954 featured the "long established, more leisurely water route across Chesapeake Bay", as the writer described the Old Bay Line, recommending "the boat trip can be made comfortably and comparatively inexpensively every night between Baltimore, Old Point Comfort and Norfolk, and on alternate nights between Washington, D.C., and the Virginia communities".

Notable Old Bay Line passenger vessels used in scheduled overnight service, with dates acquired and gross tonnages, were: At the time of the Old Bay Line's dissolution in April 1962, three ships remained docked at the Pratt Street pier: District of Columbia, which had been kept as a spare since the Washington–Norfolk service ended in 1957, was scrapped soon afterwards.

City of Richmond was sold for use as a floating restaurant in the Virgin Islands, but sank in the Atlantic Ocean off Georgetown, South Carolina, while under tow to her new home.