Banked turn

For a road or railroad this is usually due to the roadbed having a transverse down-slope towards the inside of the curve.

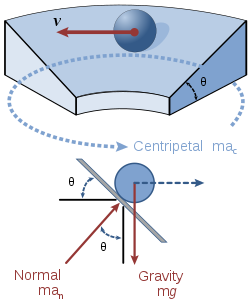

If the bank angle is zero, the surface is flat and the normal force is vertically upward.

This must be large enough to provide the centripetal force, a relationship that can be expressed as an inequality, assuming the car is driving in a circle of radius

: The expression on the right hand side is the centripetal acceleration multiplied by mass, the force required to turn the vehicle.

This also ignores effects such as downforce, which can increase the normal force and cornering speed.

As opposed to a vehicle riding along a flat circle, inclined edges add an additional force that keeps the vehicle in its path and prevents a car from being "dragged into" or "pushed out of" the circle (or a railroad wheel from moving sideways so as to nearly rub on the wheel flange).

In the absence of friction, the normal force is the only one acting on the vehicle in the direction of the center of the circle.

Therefore, as per Newton's second law, we can set the horizontal component of the normal force equal to mass multiplied by centripetal acceleration:[1] Because there is no motion in the vertical direction, the sum of all vertical forces acting on the system must be zero.

Therefore, we can set the vertical component of the vehicle's normal force equal to its weight:[1] Solving the above equation for the normal force and substituting this value into our previous equation, we get: This is equivalent to: Solving for velocity we have: This provides the velocity that in the absence of friction and with a given angle of incline and radius of curvature, will ensure that the vehicle will remain in its designated path.

When calculating a maximum velocity for our automobile, friction will point down the incline and towards the center of the circle.

These forces include the vertical component of the normal force pointing upwards and both the car's weight and the vertical component of friction pointing downwards: By solving the above equation for mass and substituting this value into our previous equation we get: Solving for

This equation provides the maximum velocity for the automobile with the given angle of incline, coefficient of static friction and radius of curvature.

The difference in the latter analysis comes when considering the direction of friction for the minimum velocity of the automobile (towards the outside of the circle).

Consequently, opposite operations are performed when inserting friction into equations for forces in the centripetal and vertical directions.

Improperly banked road curves increase the risk of run-off-road and head-on crashes.

[3] Up until now, highway engineers have been without efficient tools to identify improperly banked curves and to design relevant mitigating road actions.

A modern profilograph can provide data of both road curvature and cross slope (angle of incline).

A practical demonstration of how to evaluate improperly banked turns was developed in the EU Roadex III project.

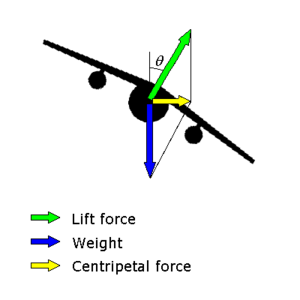

When the turn has been completed the aircraft must roll back to the wings-level position in order to resume straight flight.

If the aircraft is to continue in level flight (i.e. at constant altitude), the vertical component must continue to equal the weight of the aircraft and so the pilot must pull back on the stick to apply the elevators to pitch the nose up, and therefore increase the angle of attack, generating an increase in the lift of the wing.

Newton's second law in the horizontal direction can be expressed mathematically as: where: In straight level flight, lift is equal to the aircraft weight.