Bankruptcy of Penn Central

[1] Penn Central was responsible for a third of the nation's passenger trains and much of the freight rail in the Northeastern United States, and its failure would have devastating impacts on the Northeast's economy.

Factors leading to the bankruptcy included incompatible corporate cultures among the merger partners, excessive and duplicative rail assets, the departure of industries from the Rust Belt, and the Interstate Commerce Commission–mandated absorption of the bankrupt New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad at the end of 1968.

Despite their long history of rivalry and direct competition, and both companies maintaining profitability, the economic conditions of the 1960s convinced both railroads that they needed to merge to survive.

[1] Even Penn Central's executives could not work together—chairman of the board Stuart Saunders, from the PRR, allegedly referred to president Alfred E. Perlman from the NYC as "the worst enemy I've ever had in my life; he's cost me untold millions of dollars.

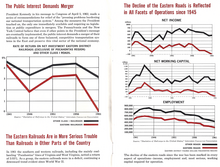

Sufficient freight traffic once existed to justify operating all of these lines, but the deindustrialization trends gripping the Rust Belt meant this was no longer true.

Penn Central was responsible for extensive intercity and commuter passenger train service, and despite industrial decline also carried significant quantities of freight.

The revived Penn Central Corporation held significant real estate assets, ranging from the oil industry to hotels and amusement parks, along with more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of former rail lines not included in Conrail or sold to other companies.