Feather

Goose and eider down have great loft, the ability to expand from a compressed, stored state to trap large amounts of compartmentalized, insulating air.

[9] Today, feathers used in fashion and in military headdresses and clothes are obtained as a waste product of poultry farming, including chickens, geese, turkeys, pheasants, and ostriches.

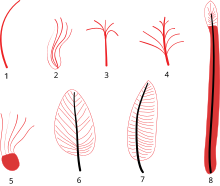

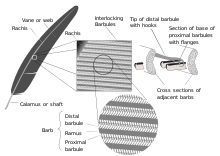

Feathers are among the most complex integumentary appendages found in vertebrates and are formed in tiny follicles in the epidermis, or outer skin layer, that produce keratin proteins.

Down feathers are fluffy because they lack barbicels, so the barbules float free of each other, allowing the down to trap air and provide excellent thermal insulation.

Striking differences in feather patterns and colors are part of the sexual dimorphism of many bird species and are particularly important in the selection of mating pairs.

[32] The colors of feathers are produced by pigments, by microscopic structures that can refract, reflect, or scatter selected wavelengths of light, or by a combination of both.

The blues and bright greens of many parrots are produced by constructive interference of light reflecting from different layers of structures in feathers.

Carotenoid-based pigments might be honest signals of fitness because they are derived from special diets and hence might be difficult to obtain,[41][42] and/or because carotenoids are required for immune function and hence sexual displays come at the expense of health.

New studies are suggesting that the unique feathers of birds are also a large influence on many important aspects of avian behavior, such as the height at which different species build their nests.

The height study found that birds that nest in the canopies of trees often have many more predator attacks due to the brighter color of feathers that the female displays.

Feather lice typically live on a single host and can move only from parents to chicks, between mating birds, and, occasionally, by phoresy.

[57] Some groups of Native people in Alaska have used ptarmigan feathers as temper (non-plastic additives) in pottery manufacture since the first millennium BC in order to promote thermal shock resistance and strength.

[58] Eagle feathers have great cultural and spiritual value to Native Americans in the United States and First Nations peoples in Canada as religious objects.

[62] During the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, there was a booming international trade in plumes for extravagant women's hats and other headgear (including in Victorian fashion).

[64][65] More recently, rooster plumage has become a popular trend as a hairstyle accessory, with feathers formerly used as fishing lures now being used to provide color and style to hair.

[73] While feathers have been suggested as having evolved from reptilian scales, there are numerous objections to that idea, and more recent explanations have arisen from the paradigm of evolutionary developmental biology.

In fossil specimens of the paravian Anchiornis huxleyi and the pterosaur Tupandactylus imperator, the features are so well preserved that the melanosome (pigment cells) structure can be observed.

[77][78] Additionally, when comparing different Ornithomimus edmontonicus specimens, older individuals were found to have a pennibrachium (a wing-like structure consisting of elongate feathers), while younger ones did not.

Another theory posits that the original adaptive advantage of early feathers was their pigmentation or iridescence, contributing to sexual preference in mate selection.

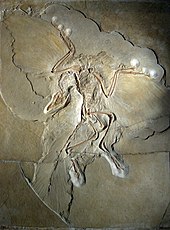

[86] Dinosaurs that had feathers or protofeathers include Pedopenna daohugouensis[87] and Dilong paradoxus, a tyrannosauroid which is 60 to 70 million years older than Tyrannosaurus rex.

Branched feathers with rachis, barbs, and barbules were discovered in many members including Sinornithosaurus millenii, a dromaeosaurid found in the Yixian formation (124.6 MYA).

[100] Previously, a temporal paradox existed in the evolution of feathers—theropods with highly derived bird-like characteristics occurred at a later time than Archaeopteryx—suggesting that the descendants of birds arose before the ancestor.

[105][106] A large phylogenetic analysis of early dinosaurs by Matthew Baron, David B. Norman and Paul Barrett (2017) found that Theropoda is actually more closely related to Ornithischia, to which it formed the sister group within the clade Ornithoscelida.

The study also suggested that if the feather-like structures of theropods and ornithischians are of common evolutionary origin then it would be possible that feathers were restricted to Ornithoscelida.

Oviraptorosauria (4, 6) Troodontidae (3+, 6) Other dromaeosaurids Sinornithosaurus (3+, 6) Microraptor (3+, 6, 7) Scansoriopterygidae (3+, 6, 8) Archaeopterygidae (3+, 6, 7) Jeholornis (6, 7) Confuciusornis (4, 6, 7, 8) Enantiornithes (4, 6, 7, 8) Neornithes (4, 6, 7, 8) Pterosaurs were long known to have filamentous fur-like structures covering their body known as pycnofibres, which were generally considered distinct from the "true feathers" of birds and their dinosaur kin.

[112] Mike Benton, the study's senior author, lent credence to the former theory, stating "We couldn't find any anatomical evidence that the four pycnofiber types are in any way different from the feathers of birds and dinosaurs.

The second type consists of tufts of filaments joined near the base, similar to the branching down feathers of birds and other coelurosaurian dinosaurs, around 2.5–8.0 mm long and only cover the wing membranes.

Studies of sampled pycnofibres revealed the presence of microbodies within the filaments, resembling the melanosome pigments identified in other fossil integuments, specifically phaeomelanosomes.

[118] The identity of these branching structures as pycnofibres or feathers was challenged by Unwin & Martill (2020), who interpreted them as bunched-up and degraded aktinofibrils–stiffening fibres found in the wing membrane of pterosaurs–and attributed the melanosomes and keratin to skin rather than filaments.

Further, they argue that the restriction of melanosomes and keratin to the fibres, as occurs in fossil dinosaur feathers, supports the case they are filaments and is not consistent with contamination from preserved skin.

- Vane

- Shaft, rachis

- Barb

- Aftershaft, afterfeather

- Quill, calamus

Left: turacin (red) and turacoverdin (green, with some structural blue iridescence at lower end) on the wing of Tauraco bannermani

Right: carotenoids (red) and melanins (dark) on belly/wings of Ramphocelus bresilius