Mexican featherwork

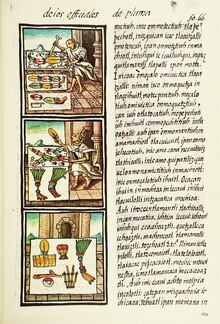

Mexican featherwork, also called "plumería", was an important artistic and decorative technique in the pre-Hispanic and colonial periods in what is now Mexico.

At the beginning of the 17th century, it began a decline due to the death of the old masters, the disappearance of the birds that provide fine feathers and the depreciation of indigenous handiwork.

[4] Much of this symbolism arose with the spread of the worship of the Toltec god/king Quetzalcoatl, depicted as a serpent covered in quetzal feathers.

He was born fully armed with an eagle feather shield, fine plumage in his head and on his left sandal.

[1] Feathers were used to make many types of objects from arrows, fly whisks, fans, complicated headdresses and fine clothing.

These include the mountain trogon, lovely cotinga, roseate spoonbill, squirrel cuckoo, red-legged honeycreeper, emerald toucanet, agami heron, russet-crowned motmot, turquoise-browed motmot, blue grosbeak, golden eagle, great egret, military macaw, scarlet macaw, yellow-headed amazon, Montezuma oropendola and the over 53 species of hummingbird found in Mexico.

[20][21] In Aztec society, the class that created feather objects was called the amanteca, named after the Amantla neighborhood in Tenochtitlan where they lived and worked.

[25] The sophistication of this art can be seen in pieces created before the Conquest, some of which are part of the collection of the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna, such as Montezuma's headdress, the ceremonial coat of arms and the great fan or fly whisk.

Among the gifts for King Charles V was artwork, including that made with feathers, such as shields with scenes of sacrifice, serpents, butterflies, birds and crests.

[38] Amantecas were creating Christian religious images within months after the arrival of the conquistadors, destined for Europe as well as Asia.

[46] The iconography of feather art images focused on founders and patron saints, along with figures related to the various religious orders.

Feather work became a popular item in the collection of kings, emperors, nobles, clergy, intellectuals and naturalists from the 16th to 18th century, with pieces reaching courts in Prague, Abras Castle, El Escorial and various other cities in Europe.

[49] European engravings were used as a model for feather images created for miters which today can be still found in Milan, Florence and New York.

[53] Other artists such as Tommaso Ghisi and Jacopo Ligozzi used the technique as well to create works for the collections of the Medicis, Aldrovandi, Settala and Rudolf II of Prague.

At this time, demand for the work declined as well, because the Spanish began to disdain indigenous handcrafts and oil painting became preferred for the production of religious images.

[38][55] In the 17th-century, imagery done in feather work became more varied, including the Virgin of Guadalupe and those from European mythology, especially on fans for ladies.

Feather work was supplemented with the use of oil paint to depict people (especially faces and hands), landscapes and animals and tiny strips of paper were dropped along with the outer borders.

Frances Calderon de la Barca noted that the mosaics of saints and angels were crude in drawing but exquisite in coloring.

Painter and tapestry weaver Carmen Padin began researching the technique after hearing Fernando Gamboa lament its loss.

His image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was given by Mexican president Luis Echeverría to Pope John XXIII and is part of the Vatican's collection.

Grandson Hans Matias Olay specializes in reproducing the birds and flowers that the Nahuas in Guerrero paint on amate paper.

In 1990, the National Museum of Anthropology held an exhibit of works by Gabriel Olay Ramos and his sisters Gloria and Esperanza.

A feather object can last indefinitely if it is preserved in a hermetically sealed case of inert gas, with a fixed humidity, darkness and low temperature.

These objects can be exhibited in galleries, museums and private collections with minimal decay if temperature and humidity are controlled and light kept to a minimum.

[27] Because of the sending of many fine feather mosaics to Europe, a number of important pieces are located in museums and other collections on that continent.

The oldest feather piece created by Christian indigenous workers is the Misa de San Gregorio at the Museum of the Jacobins in Auch, France.

It is dated 1539 and given as a gift to Pope Paul III by Antonio de Mendoza, according to the inscription, following the papal bull that declared the indigenous to be endowed with reason and able to fully participate in Catholic rites.

[45][72] Another notable work is from the 19th-century called San Lucas pintando a la Virgen, located in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris.

[59] Another piece in this museum is the Virgen del Rosario, from the 17th century, with the imagery of the Rosary important to counter Islam and Protestantism.

Against this background are small pieces of paper sewn on, then with colored feathers glued to these to form floral wreath patterns.