Georges-Eugène Haussmann

His paternal grandfather Nicolas Haussmann [fr] was a deputy of the Legislative Assembly and National Convention, an administrator of the department of Seine-et-Oise and a commissioner to the army.

His maternal grandfather was a general and a deputy of the National Convention: Georges Frédéric Dentzel [fr], a baron of Napoleon's First Empire.

[2] Haussmann joined his father as an insurgent in the July Revolution of 1830, which deposed the Bourbon king Charles X in favor of his cousin, Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans.

Despite proving himself as a hard worker and able representative of the government, his arrogance, dictatorial manner, and habit of impeding his superiors led to his being continually passed over for promotion to prefect.

He was deemed to be a loyal holdover from the civil service of the July Monarchy, and shortly after their meeting Louis Napoléon granted Haussmann a promotion to prefect of the Var Department at Draguignan.

In November 1852, a plebiscite overwhelmingly approved Napoleon's assumption of the throne, and he soon began searching for a new prefect of the Seine to carry out his Paris reconstruction program.

[7] The emperor's minister of the interior, Victor de Persigny, interviewed the prefects of Rouen, Lille, Lyon, Marseille and Bordeaux for the Paris post.

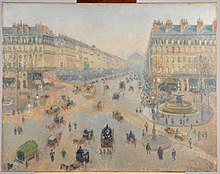

[9] Napoleon III and Haussmann launched a series of enormous public works projects in Paris, hiring tens of thousands of workers to improve the sanitation, water supply and traffic circulation of the city.

To a degree the boulevard system was planned as a mechanism for the easy deployment of troops and artillery, but its main purpose was to help relieve traffic congestion in a dense city and interconnect its landmark buildings.

To accommodate the growing population and those who would be forced from the centre by the new boulevards and squares Napoleon III planned to build, he issued a decree annexing eleven surrounding communes, and increasing the number of arrondissements from twelve to twenty, which enlarged the city to its modern boundaries.

Buildings along these avenues were required to be the same height and in a similar style, and to be faced with cream-coloured stone, creating the uniform look of Paris boulevards.

"On his own estimation the new boulevards and open spaces displaced 350,000 people; ... by 1870 one-fifth of the streets in central Paris were his creation; he had spent ... 2.5 billion francs on the city; ... one in five Parisian workers was employed in the building trade".

He completed Les Halles, the great iron and glass produce market in the centre of the city, and built a new municipal hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, in the place of crumbling medieval buildings on the Ile de la Cité.

Working with Haussmann and Adolphe Alphand, the engineer who headed the new Service of Promenades and Plantations, he laid out a plan for four major parks at the cardinal points of the compass around the city.

Thousands of workers and gardeners began to dig lakes, build cascades, plant lawns, flowerbeds, trees, and construct chalets and grottoes.

When the Emperor and Empress attended a performance at the Odeon Theater, near the Luxembourg gardens, members of the audience shouted "Dismiss Haussmann!"

In his memoires, Haussmann had this comment on his dismissal: "In the eyes of the Parisians, who like routine in things but are changeable when it comes to people, I committed two great wrongs; over the course of seventeen years I disturbed their daily habits by turning Paris upside down, and they had to look at the same face of the Prefect in the Hotel de Ville.

"[24] After the fall of Napoleon III, Haussmann spent about a year abroad, but he re-entered public life in 1877, when he became Bonapartist deputy for Ajaccio.

After the Paris International Exposition of 1867, William I, the King of Prussia, carried back to Berlin a large map showing Haussmann's projects, which influenced the future planning of that city.

Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of Central Park in New York, visited the Bois de Boulogne eight times during his 1859 study trip to Europe, and was also influenced by the innovations of the Parc des Buttes Chaumont.

The company also built rows of luxury shops under a covered arcade along the Rue de Rivoli and around the hotel, which they rented to shopkeepers.

On 14 November 1858, Napoleon and Haussmann created the Caisse des travaux de la Ville, specifically to finance the reconstruction projects.

I saw a swan that had broken out of its cage, webbed feet clumsy on the cobblestones, white feathers dragging through uneven ruts, and obstinately pecking at the drains ... Paris changes ... but in sadness like mine nothing stirs—new buildings, old neighbourhoods turn to allegory,

Besides pointing out the repressive aims that were achieved by Haussmann's urbanism, Guy Debord and his friends, who considered urbanism to be a "state science" or inherently "capitalist" science, also underlined that he nicely separated leisure areas from work places, thus announcing modern functionalism, as illustrated by Le Corbusier's precise zone tripartition, with one zone for circulation, one for housing, and one for labour.

"[35] Some critics and historians in the 20th century, notably Lewis Mumford, argued that the real purpose of Haussmann's boulevards was to make it easier for the army to crush popular uprisings.

According to these critics, the wide boulevards gave the army greater mobility, a wider range of fire for their cannon, and made it harder to block streets with barricades.

Their main purpose, according to Napoleon III and Haussmann, was to improve traffic circulation, provide space and light and views of the city landmarks, and to beautify Paris.

"[39] He admitted he sometimes used this argument with the parliament to justify the high cost of his projects, arguing that they were for national defense and should be paid for, at least partially, by the state.

"[39] The Paris urban historian Patrice de Moncan wrote: "To see the works created by Haussmann and Napoleon III only from the perspective of their strategic value is very reductive.

His desire to make Paris, the economic capital of France, a more open, more healthy city, not only for the upper classes but also for the workers, cannot be denied, and should be recognised as the primary motivation.