Compass

When the compass is held level, the needle turns until, after a few seconds to allow oscillations to die out, it settles into its equilibrium orientation.

The locations of the Earth's magnetic poles slowly change with time, which is referred to as geomagnetic secular variation.

[12] The ancient Indian medical text Sushruta Samhita describes using magnetic properties of the lodestone to remove arrows embedded in a person's body.

[citation needed] The earliest Chinese literary reference to magnetism occurs in the 4th-century BC Book of the Devil Valley Master (Guiguzi).

"[14][15] Some claims state that the first compasses in ancient Han dynasty China were made of lodestone, a naturally magnetized ore of iron.

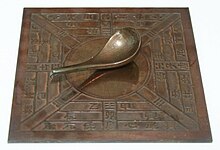

"[17] In the 2nd century BC, Chinese geomancers were experimenting with the magnetic properties of lodestone to make a "south-pointing spoon" for divination.

[22][23] Later compasses were made of iron needles, magnetized by striking them with a lodestone, which appeared in China by 1088 during the Song dynasty, as described by Shen Kuo.

[27] The liquid inside the capsule serves to damp the movement of the needle, reducing oscillation time and increasing stability.

This type of compass uses a separate magnetized needle inside a rotating capsule, an orienting "box" or gate for aligning the needle with magnetic north, a transparent base containing map orienting lines, and a bezel (outer dial) marked in degrees or other units of angular measurement.

for taking bearings of distant objects with greater precision, gimbal-mounted, "global" needles for use in differing hemispheres, special rare-earth magnets to stabilize compass needles, adjustable declination for obtaining instant true bearings without resorting to arithmetic, and devices such as inclinometers for measuring gradients.

[30] The sport of orienteering has also resulted in the development of models with extremely fast-settling and stable needles utilizing rare-earth magnets for optimal use with a topographic map, a land navigation technique known as terrain association.

Magnetic card compass designs normally require a separate protractor tool in order to take bearings directly from a map.

[33][34] The U.S. M-1950 military lensatic compass does not use a liquid-filled capsule as a damping mechanism, but rather electromagnetic induction to control oscillation of its magnetized card.

[35] As induction forces provide less damping than fluid-filled designs, a needle lock is fitted to the compass to reduce wear, operated by the folding action of the rear sight/lens holder.

The use of air-filled induction compasses has declined over the years, as they may become inoperative or inaccurate in freezing temperatures or extremely humid environments due to condensation or water ingress.

This is an approximation of a milli-radian (6283 per circle), in which the compass dial is spaced into 6400 units or "mils" for additional precision when measuring angles, laying artillery, etc.

This system was adopted by the former Warsaw Pact countries, e.g., the Soviet Union, East Germany, etc., often counterclockwise (see picture of wrist compass).

This individual zone balancing prevents excessive dipping of one end of the needle, which can cause the compass card to stick and give false readings.

Compasses used for wilderness land navigation should not be used in proximity to ferrous metal objects or electromagnetic fields (car electrical systems, automobile engines, steel pitons, etc.)

[47] Compasses are particularly difficult to use accurately in or near trucks, cars or other mechanized vehicles even when corrected for deviation by the use of built-in magnets or other devices.

Large amounts of ferrous metal combined with the on-and-off electrical fields caused by the vehicle's ignition and charging systems generally result in significant compass errors.

At sea, a ship's compass must also be corrected for errors, called deviation, caused by iron and steel in its structure and equipment.

Except in areas of extreme magnetic declination variance (20 degrees or more), this is enough to protect from walking in a substantially different direction than expected over short distances, provided the terrain is fairly flat and visibility is not impaired.

By carefully recording distances (time or paces) and magnetic bearings traveled, one can plot a course and return to one's starting point using the compass alone.

To check one's progress along a course or azimuth, or to ensure that the object in view is indeed the destination, a new compass reading may be taken to the target if visible (here, the large mountain).

It is a non-magnetic compass that finds true north by using an (electrically powered) fast-spinning wheel and friction forces in order to exploit the rotation of the Earth.

GPS receivers using two or more antennae mounted separately and blending the data with an inertial motion unit (IMU) can now achieve 0.02° in heading accuracy and have startup times in seconds rather than hours for gyrocompass systems.

The devices accurately determine the positions (latitudes, longitudes and altitude) of the antennae on the Earth, from which the cardinal directions can be calculated.

Additionally, compared with gyrocompasses, they are much cheaper, they work better in polar regions, they are less prone to be affected by mechanical vibration, and they can be initialized far more quickly.

However, they depend on the functioning of, and communication with, the GPS satellites, which might be disrupted by an electronic attack or by the effects of a severe solar storm.