Philippine revolts against Spain

Some revolts stemmed from land problems and this was largely the cause of the insurrections that transpired in the agricultural provinces of Batangas, Ilocos sur, Cavite, and Laguna.

In Mindanao and Sulu, a continuous fight for sovereignty was sustained by the Moro people and their allies for the whole duration of Spanish conquest and rule.

The Pampanga Revolt was an uprising in 1585 by some native Kapampangan leaders who resented the Spanish landowners, or encomenderos, who had deprived them of their historical land inheritances as tribal chiefs or datus.

In 1583, Kapampangans were forced to work in the goldmines of Ilocos and not allowed to return in time for the planting season, causing a severe food shortage and eventual famine, leading to mass deaths throughout Pampanga in 1584.

Spanish and Filipino colonial troops were sent by Governor-General Santiago de Vera, and the leaders of the revolt were arrested and summarily executed by Christian Cruz-Herrera.

The Chinese inhabitants of Manila set fire to Legarda and Binondo and for a time threatened to capture the Moro stronghold in Intramuros.

With a babaylan, or religious leader named Pagali, he built a temple for a diwata or local goddess, and pressed six towns to rise up in revolt.

Similar to the Tamblot Uprising, Pagali used magic to attract followers, and claimed that they could turn the Spaniards into clay by hurling bits of earth at them.

Miguel Lanab and Alababan killed, beheaded, and mutilated two Dominican missionaries, Father Alonzo Garcia and Brother Onofre Palao, who were sent by the Spanish colonial government to convert the Itneg people to Christianity.

Afterwards, they compelled their fellow Itnegs to loot, desecrate Catholic images, set fire to the local churches, and escape with them to the mountains.

His trusted co-conspirator David Dula sustained the quest for freedom with greater vigor but in a fierce battle several years later, he was wounded, captured, and later executed in Palapag, Northern Samar by the Spaniards together with his seven key lieutenants.

After hearing news of a Kapampangan chief siding with the Spaniards, Maniago and his forces arranged for a meeting with Governor-General Sabiniano Manrique de Lara in which they gave their conditions to end their rebellion.

The letters sent by Don Andres Malong ("King of Pangasinan") narrating the defeat of the Spaniards in his area and urging other provinces to rise in arms failed to obtain any support among the natives.

Tapar and his men were killed in a bloody skirmish against Spanish and colonial foot soldier troops and their corpses were impaled on stakes.

Some 19,000 survivors were granted pardon and were eventually allowed to live in new Boholano villages: namely, the present-day towns of Balilihan, Batuan, Bilar (Vilar), Catigbian, and Sevilla (Cabulao).

The case was eventually investigated by Spanish officials and was even heard in the court of Ferdinand VI in which he ordered the priests to return the lands they seized.

The battles of the Silang revolt are a prime example of the use of divide et impera, since Spanish troops largely used Kapampangan soldiers to fight the Ilocanos.

During the British invasion of Manila during the Seven Years' War, the Spanish colonial government, including Villacorta, had relocated to Bacolor in the province of Pampanga, which was then adjacent to Pangasinan.

The town leaders demanded that the governor be removed and that the colonial government stop collecting taxes since the islands were already under British control at that time.

Pangasinenses took over all official functions and controlled the province up to the Agno River, the natural boundary between Pangasinan and neighboring Pampanga in the south.

The Spanish friars, who were allowed to stay in the province, also started a campaign to persuade Pangasinan residents of the futility of the Palaris Revolt.

By March 1764, most of the province had already fallen, leaving Palaris no escape route except through Lingayen Gulf and the South China Sea in the west.

But his presence terrified his protectors and his own sister Simeona, who was apparently threatened by the Spanish clergy, betrayed him to Agustín Matias, the gobernadorcillo (mayor) of the razed Binalatongan.

Basi wine held significant cultural and societal importance for the Ilocanos, being integral to rituals surrounding childbirth, marriage, and death.

A series of 14 paintings on the Basi Revolt by Esteban Pichay Villanueva currently hangs at the Ilocos Sur National Museum in Vigan City.

On the night of June 1, 1823, he along with some subordinates in the King's Regiment, composed mainly of Mexicans with some creoles and mestizos from the now independent nations of Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina and Costa Rica,[20] started a revolt.

They eventually failed to seize Fort Santiago because Andrés' brother Mariano, commanding the citadel, refused to open its gates.

In the same year, two Palmero brothers, members of a prominent clan in the Philippines, along with other people from both the military and the civil service, planned to seize the government.

Due to the concentration of Spanish religious power and authority in the already-established religious orders (the Augustinians, Jesuits, and Franciscans to name a few) and the concept that Filipino priests should only stay in the church and not the convent and vice versa (although this was not always followed), the Spanish government banned the new order, especially due to its deviation from original Catholic rituals and teachings, such as prayers and rituals which inculcated paganic practices.

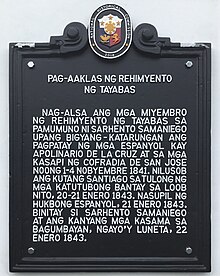

Because of this, the Spanish government sent in troops to forcibly break up the order, forcing De la Cruz and his followers to rise in armed revolt in self-defense.