Batavi (Germanic tribe)

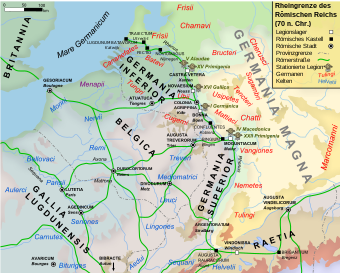

Tacitus also reports that before their arrival the area had been "an uninhabited district on the extremity of the coast of Gaul, and also of a neighbouring island, surrounded by the ocean in front, and by the river Rhine in the rear and on either side".

[6] Tacitus (De origine et situ Germanorum XXIX) described the Batavi as the bravest of the tribes of the area, hardened in the Germanic wars, with cohorts under their own commanders transferred to Britannia.

Dio Cassius describes this surprise tactic employed by Aulus Plautius against the "barbarians"—the British Celts— at the battle of the River Medway, 43: The barbarians thought that Romans would not be able to cross it without a bridge, and consequently bivouacked in rather careless fashion on the opposite bank; but he sent across a detachment of Germanic tribesmen, who were accustomed to swim easily in full armour across the most turbulent streams.

The late fourth century writer on Roman military affairs Vegetius mentions soldiers using reed rafts, drawn by leather leads, to transport equipment across rivers.

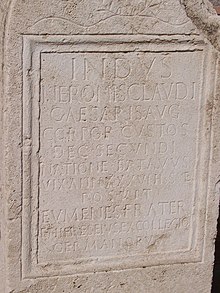

[8] Since the shields were wooden, they may have provided sufficient buoyancy The Batavi were used to form the bulk of the Emperor's personal Germanic bodyguard from Augustus to Galba.

A Batavian contingent was used in an amphibious assault on Ynys Mon (Anglesey), taking the assembled Druids by surprise, as they were only expecting Roman ships.

Despite the alliance, one of the high-ranking Batavi, Julius Paullus, to give him his Roman name, was executed by Fonteius Capito on a false charge of rebellion.

The Batavi were still mentioned in 355 during the reign of Constantius II (317–361), when their island was already dominated by the Salii, a Frankish tribe that had sought Roman protection there in 297 after having been expelled from their own country by the Saxons.

In the 16th-century emergence of a popular foundation story and origin myth for the Dutch people, the Batavians came to be regarded as their ancestors during their national struggle for independence during the Eighty Years' War.

[11][12] The mix of fancy and fact in the Cronyke van Hollandt, Zeelandt ende Vriesland (called the Divisiekroniek) by the Augustinian friar and humanist Cornelius Gerardi Aurelius, first published in 1517, brought the spare remarks in Tacitus' newly rediscovered Germania to a popular public; it was being reprinted as late as 1802.

[13] Contemporary Dutch virtues of independence, fortitude and industry were fully recognizable among the Batavians in more scholarly history represented in Hugo Grotius' Liber de Antiquitate Republicae Batavicorum (1610).

The origin was perpetuated by Romeyn de Hooghe's Spiegel van Staat der Vereenigden Nederlanden ("Mirror of the State of the United Netherlands," 1706), which also ran to many editions, and it was revived in the atmosphere of Romantic nationalism in the late eighteenth-century reforms that saw a short-lived Batavian Republic and, in the colony of the Dutch East Indies, a capital that was named Batavia.