Nero

In the early years of his reign, Nero was advised and guided by his mother Agrippina, his tutor Seneca the Younger, and his praetorian prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus, but sought to rule independently and rid himself of restraining influences.

Tacitus claims Nero seized Christians as scapegoats for the fire and had them burned alive, seemingly motivated not by public justice, but personal cruelty.

According to Jürgen Malitz, Suetonius tells that Nero's father was known to be "irascible and brutal", and that both "enjoyed chariot races and theater performances to a degree not befitting their position".

[5] Suetonius also mentions that when Nero's father Domitius was congratulated by his friends for the birth of his son, he replied that any child born to him and Agrippina would have a detestable nature and become a public danger.

[20] They found Nero's construction projects overly extravagant and claim that their cost left Italy "thoroughly exhausted by contributions of money" with "the provinces ruined".

[21][22] Modern historians note that the period was riddled with deflation and that Nero intended his spending on public-work and charities to ease economic troubles.

Shotter writes the following about Agrippina's deteriorating relationship with Nero: "What Seneca and Burrus probably saw as relatively harmless in Nero—his cultural pursuits and his affair with the slave girl Claudia Acte—were to her signs of her son's dangerous emancipation of himself from her influence."

[25] Jürgen Malitz writes that ancient sources do not provide any clear evidence to evaluate the extent of Nero's personal involvement in politics during the first years of his reign.

[3][34] The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome cautiously notes that Nero's reasons for killing his mother in AD 59 are "not fully understood".

[57][58] Tacitus, Cassius Dio, and modern archaeology describe the destruction of mansions, ordinary residences, public buildings, and temples on the Aventine, Palatine, and Caelian hills.

[60][61] Some Romans thought the fire an accident, as the merchant shops were timber-framed and sold flammable goods, and the outer seating stands of the Circus were timber-built.

The accounts by Pliny the Elder, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio suggest several possible reasons for Nero's alleged arson, including his creation of a real-life backdrop to a theatrical performance about the burning of Troy.

[66][67][68] The popular legend that Nero played the lyre while Rome burned "is at least partly a literary construct of Flavian propaganda ... which looked askance on the abortive Neronian attempt to rewrite Augustan models of rule".

[70][71] After the fire, Nero opened his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless, and arranged for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors.

[f] In AD 65, Gaius Calpurnius Piso, a Roman statesman, organized a conspiracy against Nero with the help of Subrius Flavus and Sulpicius Asper, a tribune and a centurion of the Praetorian Guard.

Modern historians, noting the probable biases of Suetonius, Tacitus, and Cassius Dio, and the likely absence of eyewitnesses to such an event, propose that Poppaea may have died after miscarriage or in childbirth.

[89] In an attempt to gain support from outside his own province, Vindex called upon Servius Sulpicius Galba, the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, to join the rebellion and to declare himself emperor in opposition to Nero.

According to Suetonius, Nero abandoned the idea when some army officers openly refused to obey his commands, responding with a line from Virgil's Aeneid: "Is it so dreadful a thing then to die?"

Nero then toyed with the idea of fleeing to Parthia, throwing himself upon the mercy of Galba, or appealing to the people and begging them to pardon him for his past offences "and if he could not soften their hearts, to entreat them at least to allow him the prefecture of Egypt".

Suetonius reports that the text of this speech was later found in Nero's writing desk, but that he dared not give it from fear of being torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum.

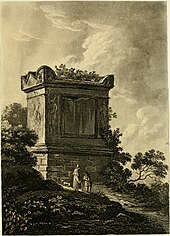

[96] He died on 9 June 68,[g] the anniversary of the death of his first wife, Claudia Octavia, and was buried in the Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, in what is now the Villa Borghese (Pincian Hill) area of Rome.

[110] Damaged portraits of Nero, often with hammer blows directed to the face, have been found in many provinces of the Roman Empire, three recently having been identified from the United Kingdom.

[122] Under Queen Boudica, the towns of Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St. Albans) were burned, and a substantial body of Roman legion infantry were eliminated.

[125] Nero began preparing for war in the early years of his reign, after the Parthian king Vologeses set his brother Tiridates on the Armenian throne.

Pliny described Nero as an "actor-emperor" (scaenici imperatoris) and Suetonius wrote that he was "carried away by a craze for popularity...since he was acclaimed as the equal of Apollo in music and of the Sun in driving a chariot, he had planned to emulate the exploits of Hercules as well.

[citation needed] Dio Chrysostom (c. 40–120), a Greek philosopher and historian, wrote the Roman people were very happy with Nero and would have allowed him to rule indefinitely.

He also thought that existing writing on them was unbalanced: The histories of Tiberius, Caius, Claudius and Nero, while they were in power, were falsified through terror, and after their death were written under the irritation of a recent hatred.

[150] In 1562, Girolamo Cardano published in Basel his Encomium Neronis, which was one of the first historical references of the modern era to portray Nero in a positive light.

The Talmud adds that the sage Reb Meir Baal HaNess lived in the time of the Mishnah, and was a prominent supporter of the Bar Kokhba rebellion against Roman rule.

[159] However, Suetonius writes that, "since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, the [emperor Claudius] expelled them from Rome" ("Iudaeos impulsore Chresto assidue tumultuantis Roma expulit").