Battle of Coronel

Although Spee had an easy victory, destroying two enemy armoured cruisers for just three men injured, the engagement also cost him almost half his supply of ammunition, which was irreplaceable.

Shock at the British losses led the Admiralty to send more ships, including two modern battlecruisers, which in turn destroyed Spee and the majority of his squadron on 8 December at the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

[2] On 4 October 1914, the British learned from an intercepted radio message that Spee planned to attack shipping on the trade routes along the west coast of South America.

The Admiralty had planned to reinforce the squadron by sending the newer and more powerful armoured cruiser HMS Defence from the Mediterranean, but temporarily diverted this ship to patrol the western Atlantic.

[3] The change of plan meant that the British squadron comprised obsolete or lightly armed vessels, crewed in the case of Good Hope by inexperienced naval reservists.

Scharnhorst and Gneisenau carried eight 8.2-inch guns each, which gave them an overwhelming advantage in range and firepower; the crews of both ships had earned accolades for their gunnery before the war.

[5][6] The Admiralty ordered Cradock to "be prepared to meet them in company", with no effort being made to clarify what action he was expected to take should he find Spee.

The two groups would operate on the east and west coasts of South America to counter the possibility of Spee slipping past Cradock into the Atlantic Ocean.

The Admiralty agreed and established the east coast squadron under Rear-Admiral Archibald Stoddart, consisting of three cruisers and two armed merchantmen.

Cradock sailed from the Falklands on 20 October, still under the impression that Defence would soon arrive and with Admiralty orders to attack German merchant ships and to seek out the East Asiatic Squadron.

[8] On 30 October, before the battle but due to communications delays too late to have any effect, Admiral Jackie Fisher was re-appointed First Sea Lord, replacing Prince Louis of Battenberg, who, along with Churchill, had been preoccupied with fighting to keep his position as First Sea Lord in the face of widespread concern over the senior British Admiral being of German descent.

The crisis drew the attention of the most senior members of the Admiralty away from the events in South America: Churchill later claimed that if he had not been distracted, he would have questioned the intentions of his admiral at sea more deeply.

[9] A signal from Cradock was received by Churchill on 27 October, advising the Admiralty of his intention to leave Canopus behind because of her slow speed and, as previously instructed, to take his remaining ships in search of Spee.

[10] Cradock probably received Churchill's reply on 1 November with the messages collected by Glasgow at Coronel, giving him time to read it before the battle.

Departing from Stanley he had left behind a letter to be forwarded to Admiral of the Fleet Sir Hedworth Meux in the event of his death.

In this, he commented that he did not intend to suffer the fate of Rear Admiral Ernest Troubridge, a friend of Cradock, who at the time was awaiting court-martial for failing to engage the enemy.

At the time Rear Admiral Ernest Troubridge, a friend of Cradock, was awaiting court-martial for failing to engage the enemy, and he had been told by the Admiralty that his force was "sufficient".

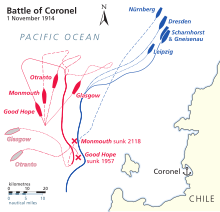

Spee decided to move his ships to Coronel to trap Glasgow while Admiral Cradock hurried north to catch Leipzig.

At 13:05, the ships formed into a line abreast formation 15 mi (13.0 nmi; 24.1 km) apart, with Glasgow at the eastern end, and started to steam north at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) searching for Leipzig.

Spee ordered full speed so that Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig were approaching the British at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), with the slower light cruisers Dresden and Nürnberg some way behind.

The German ships slowed at a range of 15,000 yd (13,720 m) to reorganise themselves for best positions, and to await best visibility, when the British to their west would be outlined against the setting sun.

Once news of the defeat reached the Admiralty, a new naval force was assembled under Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee, including the battlecruisers HMS Invincible and her sister-ship Inflexible.

[25] Otranto steamed 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) out into the Pacific Ocean before turning south and rounding Cape Horn.

Sturdee was ordered to travel with the battlecruisers HMS Invincible and Inflexible—then attached to the Grand Fleet in the North Sea—to command a new squadron with clear superiority over Spee.

[27] The official explanation of the defeat as presented to the House of Commons by Winston Churchill was: "feeling he could not bring the enemy immediately to action as long as he kept with Canopus, he decided to attack them with his fast ships alone, in the belief that even if he himself were destroyed... he would inflict damage on them which ...would lead to their certain subsequent destruction.

Along with two plaques depicting HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth, it has a central dedication plaque (in Spanish) which reads In memory of the 1,418 officers and sailors of the British military squadron and their Commander-in-Chief, Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, Royal Navy, who sacrificed their lives in the Naval Battle of Coronel, on 1 November 1914.