Battle of Drepana

Pulcher was blockading the Carthaginian stronghold of Lilybaeum (modern Marsala) when he decided to attack their fleet, which was in the harbour of the nearby city of Drepana.

The Romans were pinned against the shore, and after a day of fighting were heavily defeated by the more manoeuvrable Carthaginian ships with their better-trained crews.

It was Carthage's greatest naval victory of the war; they turned to the maritime offensive after Drepana and all but swept the Romans from the sea.

It was seven years before Rome again attempted to field a substantial fleet, while Carthage put most of its ships into reserve to save money and free up manpower.

[2][3] His works include a now-lost manual on military tactics,[4] but he is known today for The Histories, written sometime after 146 BC, or about a century after the Battle of Drepana.

[6][7] Carthaginian written records were destroyed along with their capital, Carthage, in 146 BC and so Polybius's account of the First Punic War is based on several, now-lost, Greek and Latin sources.

[21] Carthage was a well-established maritime power in the western Mediterranean; Rome had recently unified mainland Italy south of the River Arno under its control.

[24] The Carthaginians were engaging in their traditional policy of waiting for their opponents to wear themselves out, in the expectation of then regaining some or all of their possessions and negotiating a mutually satisfactory peace treaty.

[25] In 260 BC the Romans built a large fleet and over the following ten years defeated the Carthaginians in a succession of naval battles.

[38] This allowed Roman legionaries acting as marines to board enemy ships and capture them, rather than employing the previously traditional tactic of ramming.

All warships were equipped with a ram, a triple set of 60-centimetre-wide (2 ft) bronze blades weighing up to 270 kilograms (600 lb) positioned at the waterline.

[43][44][45] In 255 BC the Roman fleet was devastated by a storm while returning from Africa, with 384 ships sunk from a total of 464[note 3] and 100,000 men lost.

[49] During 252 and 251 BC the Roman army avoided battle, according to Polybius because they feared the war elephants which the Carthaginians had shipped to Sicily.

[52] Contemporary accounts do not report either side's other losses, and modern historians consider later claims of 20,000–30,000 Carthaginian casualties improbable.

A large army commanded by the year's consuls Publius Claudius Pulcher and Lucius Junius Pullus besieged the city.

[54] Early in the blockade, 50 Carthaginian quinqueremes gathered off the Aegates Islands, which lie 15–40 kilometres (9–25 mi) to the west of Sicily.

They made repeated attempts to block the harbour entrance with a heavy timber boom, but due to the prevailing sea conditions they were unsuccessful.

Pulcher, the senior consul, supported by a council of war, believed these gave him sufficient advantage to risk an attack on the Carthaginian fleet at Drepana, 25 kilometres (16 mi) north of Lilybaeum along the west coast of Sicily.

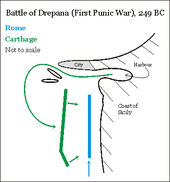

[65] Meanwhile, Adherbal led his fleet past the confused Roman vanguard and continued west, passing between the city and two small islands to reach the open sea.

The Carthaginians managed to get five ships south of Pulcher's flagship, echeloned towards the shore, and so cut off the entire Roman fleet from its line of retreat to Lilybaeum.

The Carthaginians had the additional advantage that if an individual ship was getting the worse of a melee, it could reverse oars and withdraw; if the Roman vessel followed up, it left both of its flanks vulnerable.

A little later, he harried a Roman supply convoy of 800 transports, escorted by 120 warships, to such good effect that it was caught by a storm which sank all the vessels except for two.

[78] The absence of Roman fleets then led Carthage to gradually decommission its navy, reducing the financial strain of building, maintaining and repairing ships, and providing and provisioning their crews.

[83] Pulcher's sister, Claudia, became infamous when, obstructed in a street blocked by poorer citizens, she wished aloud that her brother would lose another battle so as to thin the crowd.

The Romans had built over 1,000 galleys during the war; and this experience of building, manning, training, supplying and maintaining such numbers of ships laid the foundation for Rome's maritime dominance for 600 years.