Battle of Elands River (1900)

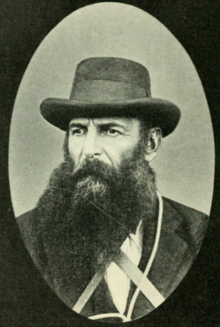

The Boer force, which consisted of several commandos under the overall leadership of Koos de la Rey, was in desperate need of provisions after earlier fighting had cut it off from its support base.

Over the course of 13 days, the Elands River supply dump was heavily shelled from several artillery pieces that were set up around the position, while Boers equipped with small arms and machine guns surrounded the garrison and kept the defenders under fire.

Following this, a series of British counter-offensives, including mounted infantry units from the Australian colonies and Canada, among others, managed to capture and secure the main population centres in South Africa by June 1900.

[4] By mid-1900, the supplies that were located at Elands River included between 1,500 and 1,750 horses, mules and cattle, a quantity of ammunition, food and other equipment worth over 100,000 pounds, and over 100 wagons.

As a result, some actions were taken to fortify the position, with a makeshift defensive perimeter being established utilising stores and wagons to create barricades.

[7][12][13] In addition to the garrison, there were civilians, consisting of Africans working as porters, drivers, or runners and about 30 loyalist European settlers who had moved to the farm prior to being evacuated.

A third firing point, about 3,900 metres (4,300 yd) away, consisting of an artillery piece and a pom-pom, engaged the garrison from high ground overlooking the river to the west.

[7] In an effort to silence the guns, a small party of Queenslanders under Lieutenant James Annat, sallied 180 metres (200 yd) to attack one of the Boer pom-pom positions, forcing its crew to pack up their weapon and withdraw.

[4] Nevertheless, the defenders continued to improve their position, constructing stone sangars and digging their fighting pits deeper,[7] reinforcing them with crates, sacks and wagon wheels.

[18] A kitchen was also established, and a makeshift hospital built in the centre of the position using several ambulances and reinforced with wagons filled with dirt and various stores and containers.

[16] After the initial heavy barrage, on the third day of the siege the Boer gunners eased their rate of fire when it became apparent that they were destroying some of the supplies they were trying to capture.

[18] In order to demonstrate the respect with which he held the defence that the garrison had put up, De la Rey offered them safe passage to British lines and was even prepared to allow the officers to retain their revolvers so that they could leave the battlefield with dignity.

As the fighting continued, the British made a second attempt to relieve the garrison, dispatching a force of about 1,000 men under Colonel Robert Baden-Powell from Rustenburg on 6 August.

Failing to allow a proper reconnaissance, around midday Baden-Powell messaged General Ian Hamilton and turned back, determining the relief effort pointless, citing previous instructions and warnings from Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in South Africa Lord Roberts about becoming isolated,[18] and claiming to have heard gun fire moving westward that suggested the garrison may have been evacuated to the west by Carrington.

[25] Based on the reports provided by Carrington upon his return, the British commanders in Pretoria and Mafeking were under the impression that the garrison had surrendered and, as a result, when Baden-Powell's force was about 30 kilometres (19 mi) away from the besieged Elands River garrison at Brakfontein, Lord Roberts ordered him and the rest of Hamilton's force at Rustenburg to return to Pretoria,[4] to focus on capturing Christiaan De Wet, an important Boer commander.

[28] The ammunition situation was also concerning de la Rey and, as it became clear that the garrison would continue to hold out, he withdrew his artillery before superior numbers of British troops arrived.

[29] That evening, a message was sent to Hore by four Western Australians from a force under Beauvoir de Lisle,[30] and Kitchener's column arrived the following day, on 16 August.

[14] Carrington's relief force from Mafeking, having been ordered to make a second attempt by Roberts, backtracked very slowly and ultimately arrived after the siege had been lifted.

[12] Although the behaviour of the defending troops was not beyond reproach, with some becoming drunk during the siege,[32] the commander of the relieving force, Lord Kitchener, told the garrison upon his arrival that their defence had been "remarkable" and that only " ... Colonials could have held out in such impossible circumstances".

[32] The garrison's performance was also later lauded by Jan Smuts, who was at the time a senior Boer commander, describing the defenders as " ... heroes who in the hour of trial ...[had risen]... nobly to the occasion".

[14] The writer, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who served in a British field hospital at Bloemfontein during 1900 and who later published a series of accounts of the conflict, also highlighted the significance of the battle in The Great Boer War.

[6] For their actions during the siege, the Rhodesian commander, Butters, and Captain Albert Duka, a medical officer from Queensland, were invested with the Distinguished Service Order.

[15] Conversely, Carrington continued nominal command of the Rhodesian Field Force, which became a paper formation, and was sent back to England by the end of the year.

[29] Over a year after the siege, on 17 September 1901, another battle was fought along a different Elands River at Modderfontein farm in the then Cape Colony,[35] where a Boer force under Smuts and Deneys Reitz overwhelmed a detachment of the 17th Lancers and raided their camp for supplies.