History of Jakarta

[1] The Dutch East Indies built up the area, before it was taken during World War II by the Empire of Japan and finally became independent as part of Indonesia.

The coastal area and port of Jakarta in northern West Java has been the location of human settlement since the 4th century BCE Buni culture.

In AD 358, King Purnawarman established Sundapura, located on the northern coast of West Java, as the new capital city for the kingdom.

Purnawarman left seven memorial stones across the area, including the present-day Banten and West Java provinces, consisting of inscriptions bearing his name.

According to the Chinese source, Chu-fan-chi, written by Chou Ju-kua in the early 13th Century, the Sumatra-based kingdom of Srivijaya ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and western Java (known as Sunda).

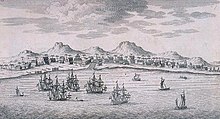

Accounts of 16th century European explorers make mention of a city called Kalapa, which apparently served as the primary port of a Hindu kingdom of Sunda.

[1][dead link] In 1522, the Portuguese secured Luso Sundanese padrão, a political and economic agreement with the Sunda Kingdom, the authority of the port.

In exchange for military assistance against the threat of the rising Islamic Javan Sultanate of Demak, Prabu Surawisesa, king of Sunda at that time, granted them free access to the pepper trade.

In 1610, Prince Jayawikarta granted permission to Dutch merchants to build a wooden godown and houses on the east bank of the Ciliwung River, opposite to Jayakarta.

[13]: 29 The rivalry was ultimately resolved in 1619, when the Dutch established a closer relationship with Banten and militarily intervened at Jayakarta, where they assumed control of the port after destroying the existing city.

[14] The new city built on the site was officially named as Batavia on January 18, 1621,[14] from which the Dutch East Indies eventually ruled the entire region.

The area, then known as Weltevreden, which include the Koningsplein, Rijswijk, Noordwijk, Tanah Abang, Kebon Sirih, and Prapatan became a popular residential, entertainment and commercial district for the European colonial elite.

This agency was composed of twelve local Javanese leaders who were regarded as loyal to the Japanese; among them were Suwiryo (who became the vice for Jakarta's schichoo) and Dahlan Abdullah.

[17] After the war, the Dutch name Batavia was internationally recognized until full Indonesian independence was achieved on 27 December 1949 and Jakarta was officially proclaimed the national capital of Indonesia.

On 19 September 1945, Sukarno held his Indonesian independence and anti-colonialism/imperialism speech, during Rapat Akbar or grand meeting at Lapangan Ikada, now the Merdeka Square.

[21] AT that time, Jalan Sudirman was largely rural and devoid of any buildings until the 1970s, with the exception of Gelora Bung Karno sports complex.

Only in late 1957, the nationalization of Dutch assets would begin, partly triggered by the anger over the refusal of the Netherlands to transfer sovereignty of Irian Jaya to Indonesia.

[25] The departure of the Dutch also caused a massive migration of the rural population into Jakarta, in response to a perception that the city was the place for economic opportunities.

The 730 hectare satellite city of Kebayoran Baru, which was conceived by the Dutch in the 1930s, remained the most important housing development in Jakarta in the 1950s.

The event was used as a trigger to complete new landmarks in Jakarta, i.e. Gelora Bung Karno Sports Complex, and so the first half of the 1960s saw large government-funded projects that were undertaken with openly nationalistic architecture.

[23] By working on the optimistic monumental projects, Sukarno hoped to put the newly independent nation's pride on international display.

Some of the notable monumental projects of Sukarno during the first half of the 1960s were: Semanggi "clover-leaf" highway interchange, a broad avenue in Central Jakarta (Jalan M.H.

He repaired and build roads, provided public transport, better sanitation, health services and educational opportunities for the poor.

Jalan Sudirman was still relatively empty, except for the Gelora Bung Karno sports complex and some housing at Bendungan Hilir and Setiabudi.

The investment of overseas capital into joint-venture property and construction projects with local developers brought many foreign architects into Indonesia.

As a result, downtown areas in Jakarta gradually resembled those of the large Western cities; and often at a high environmental cost: high-rise buildings consume huge amounts of energy in terms of air-conditioning and other services.

[33] The economic boom period of Jakarta ended abruptly in the 1997 Asian financial crisis and many projects were left abandoned.

The city became a center of violence, protest, and political maneuvering, as long-time president, Suharto, began to lose his grip on power.

Tensions reached a peak in May 1998, when four students were shot dead at Trisakti University by security forces; four days of riots ensued, resulting in damage to, or destruction of, an estimated 6,000 buildings, and the loss of 1,200 lives.

[35] In the following years, including several terms of ineffective presidents, Jakarta was a center of popular protest and national political instability.