Battle of Khe Sanh

[22][Note 2] James Marino wrote that in 1964, General William Westmoreland, the US commander in Vietnam, had determined, "Khe Sanh could serve as a patrol base blocking enemy infiltration from Laos; a base for... operations to harass the enemy in Laos; an airstrip for reconnaissance to survey the Ho Chi Minh Trail; a western anchor for the defenses south of the DMZ; and an eventual jumping-off point for ground operations to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

[25] From there, reconnaissance teams were launched into Laos to explore and gather intelligence on the PAVN logistical system known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, also known as "Truong Son Strategic Supply Route" to the North Vietnamese soldiers.

[28] In early October, the PAVN had intensified battalion-sized ground probes and sustained artillery fire against Con Thien, a hilltop stronghold in the center of the Marines' defensive line south of the DMZ, in northern Quảng Trị Province.

[27]: 432 He was vociferously opposed by General Lewis W. Walt, the Marine commander of I Corps, who argued heatedly that the real target of the American effort should be the pacification and protection of the population, not chasing the PAVN/VC in the hinterlands.

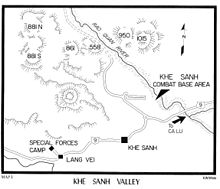

[18] : 17 To prevent PAVN observation of the main base at the airfield and their possible use as firebases, the hills of the surrounding Khe Sanh Valley had to be continuously occupied and defended by separate Marine elements.

In his memoirs, he listed the reasons for a continued effort:Khe Sanh could serve as a patrol base for blocking enemy infiltration from Laos along Route 9; as a base for SOG operations to harass the enemy in Laos; as an airstrip for reconnaissance planes surveying the Ho Chi Minh Trail; as the western anchor for defenses south of the DMZ; and as an eventual jump-off point for ground operations to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

[27]: 42 In early December 1967, the PAVN appointed Major General Trần Quý Hai as the local commander for the actions around Khe Sanh, with Lê Quang Đạo as his political commissar.

Journalist Richard Ehrlich writes that according to the report, "in late January, General Westmoreland had warned that if the situation near the DMZ and at Khe Sanh worsened drastically, nuclear or chemical weapons might have to be used."

McNamara wrote: "because of terrain and other conditions peculiar to our operations in South Vietnam, it is inconceivable that the use of nuclear weapons would be recommended there against either Viet Cong or North Vietnamese forces".

[51] During January, the recently installed electronic sensors of Operation Muscle Shoals (later renamed "Igloo White"), which were undergoing test and evaluation in southeastern Laos, were alerted by a flurry of PAVN activity along the Ho Chi Minh Trail opposite the northwestern corner of South Vietnam.

[18]: 93–94 } When weather conditions precluded FAC-directed strikes, the bombers were directed to their targets by either a Marine AN/TPQ-10 radar installation at KSCB or by Air Force Combat Skyspot MSQ-77 stations.

"[42]: 252 Meanwhile, an interservice political struggle took place in the headquarters at Phu Bai Combat Base, Saigon, and the Pentagon over who should control aviation assets supporting the entire American effort in Southeast Asia.

[55] Westmoreland insisted for several months that the entire Tet Offensive was a diversion, including, famously, attacks on downtown Saigon and obsessively affirming that the true objective of the North Vietnamese was Khe Sanh.

Although the camp's main defenses were overrun in only 13 minutes, the fighting lasted for several hours, during which the Special Forces men and Bru CIDGs managed to knock out at least five of the tanks.

Army Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Ladd (commander, 5th Special Forces Group), who had just flown in from Khe Sanh, was reportedly, "astounded that the Marines, who prided themselves on leaving no man behind, were willing to write off all of the Green Berets and simply ignore the fall of Lang Vei.

[68][18]: 111 Nevertheless, the same day that the trenches were detected, 25 February, 3rd Platoon from Bravo Company 1st Battalion, 26th Marines was ambushed on a short patrol outside the base's perimeter to test the PAVN strength.

[17]: 284 Opposition from the North Vietnamese was light and the primary problem that hampered the advance was continual heavy morning cloud cover that slowed the pace of helicopter operations.

With Company B protecting the perimeter at the rock quarry west of the combat base, the battalion moved to the line of departure at 02:30, finally leaving the positions it had defended for 73 days.

Just before noon, as the company reached the crest of the ridge, PAVN concealed in camouflaged, mutually supporting bunkers opened fire, cutting down several marines at point-blank range.

With six Marines missing in action, but presumed to be dead within the PAVN perimeter, Company G was ordered to withdraw to Hill 558 at nightfall "as a result of regimental policy to recall units to the defensive positions for the night."

With the relief of the main base by the Army, Lieutenant colonel John C. Studt, who had assumed command of the 3rd Battalion the previous month, had consolidated his companies on Hill 881 South.

Shortly after midnight, under the cover of darkness, all four companies accompanied by two scout dog teams moved along routes previously secured by patrols into assault positions in the "saddle " located between Hills 881 South and North.

Surging forward through a barren landscape of charred limbless trees and huge bomb craters, the battalion rolled up the PAVN's defenses on the southern slope of the hill.

When over 2,000 rounds of artillery fire had fallen on the objective, Company K attacked along the right flank rushing through the smoking debris of the PAVN defenses, rooting out the defenders from the ruins of bunkers and trenches.

He made his final appearance in the story of Khe Sanh on 23 May, when his regimental sergeant major and he stood before President Johnson and were presented with a Presidential Unit Citation on behalf of the 26th Marines.

The explanations given out by the Saigon command were that "the enemy had changed his tactics and reduced his forces; that PAVN had carved out new infiltration routes; that the Marines now had enough troops and helicopters to carry out mobile operations; that a fixed base was no longer necessary.

[77]: 71–72 The Marines occupied Hill 950 overlooking the Khe Sanh plateau from 1966 until September 1969 when control was handed to the Army who used the position as a SOG operations and support base until it was overrun by the PAVN in June 1971.

[77]: 152 [79] The gradual withdrawal of US forces began during 1969 and the adoption of Vietnamization meant that, by 1969, "although limited tactical offensives abounded, US military participation in the war would soon be relegated to a defensive stance.

[10] With the abandonment of the base, according to Thomas Ricks, "Khe Sanh became etched in the minds of many Americans as a symbol of the pointless sacrifice and muddled tactics that permeated a doomed U.S. war effort in Vietnam".

[27]: 55 Also, Marine Lieutenant General Victor Krulak seconded the notion that there was never a serious intention to take the base by arguing that neither the water supply nor the telephone land lines were ever cut by the PAVN.