Battle of Kunersdorf

The terrain complicated battle tactics for both sides, but the Russians and the Austrians, having arrived in the area first, were able to overcome many of its difficulties by strengthening a causeway between two small ponds.

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria had signed the treaty to gain time to rebuild her military forces and forge new alliances; she was intent upon regaining ascendancy in the Holy Roman Empire as well as reacquiring Silesia.

Recognizing the opportunity to regain her lost territories and to limit Prussia's growing power, the Empress put aside the old rivalry with France to form a new coalition.

Faced with this turn of events, Britain aligned herself with the Kingdom of Prussia; this alliance drew in not only the British king's territories held in personal union, including Hanover, but also those of his and Frederick's relatives in the Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg and the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel.

Ferdinand evicted the French from Hanover and Westphalia and re-captured the port of Emden in March 1758; he crossed the Rhine with his own forces, causing general alarm in France.

[21] The Austrian Feldmarshalleutnant Leopold Josef Graf Daun could have ended the war in October at Hochkirch, but he failed to follow up on his victory with a determined pursuit of Frederick's retreating army.

Subsequently, Pyotr Saltykov and the Russian forces advanced 110 kilometers (68 mi) west to occupy Frankfurt an der Oder on 31 July (on Germany's border with present-day Poland).

To make matters worse for the Prussians, an Austrian corps commanded by Feldmarshalleutnant Ernst Gideon von Laudon joined Saltykov on 3–5 August.

King Frederick rushed from Saxony, took over the remnants of Generalleutnant Carl Heinrich von Wedel's contingent at Müllrose and moved toward the Oder River.

[32] Saltykov established his troops on a strong position from which to receive the Prussian attack, concentrating his force in the center, which he calculated was the best way to counter-act any attempt by Frederick to deploy his deadly oblique order.

[24] While Saltykov plundered the city and prepared for Frederick's assault from the west, the Prussians reached Reitwein, some 28 km (17 mi) north of Frankfurt on 10 August, and built pontoon bridges during the night.

His redeployment took time, and the apparent hesitation in the assault confirmed to Saltykov what Frederick planned; he moved more troops around so the strongest line would face the Prussian onslaught.

The carriages pulling the biggest guns, traveling with the bulk of the army, were too wide to cross the narrow forest bridges and the columns had to be reshuffled in the woods.

By 1:00 pm, the Russian left flank had been defeated and driven back on Kunersdorf itself, leaving behind small, disorganized groups capable of only token resistance.

Saltykov fed in more units, including a force of Austrian grenadiers led by Major Joseph De Vins, and gradually the situation stabilized.

While Frederick's principal force had assaulted the Mühlberg, Johann Jakob von Wunsch, with 4,000 men, had retraced his steps from Reitwein to Frankfurt and had captured the city by mid-day.

[48] He transferred his artillery to the Mühlberg, and ordered Finck's battalions to assault the Allied salient from the northwest, while his main strike force would cross the Kuhgrund.

[37][44][49] To complete Frederick's battle plan, the Prussians would have to descend from the Mühlberg to the lower Kuhgrund, cross the spongy field, and then assault the well-defended higher ground.

The right was where it was supposed to be, with the exception of one of the support formations for the right wing, which was held up by misinformation about the ground: a couple of bridges that crossed the Huhner Fliess were too narrow for the artillery teams.

Outside the shtetl, the Prussians tried to break through the Russian line; they got as far as the Jewish cemetery at the eastern base of Judenberg, but lost two thirds of Krockow's 2nd Dragoons in the process: 484 men and 51 officers gone in minutes.

[50] The battle culminated in the early evening hours with a Prussian cavalry charge, led by von Seydlitz, upon the Russian centre and artillery positions, a futile effort.

His scouts had discovered a crossing past the chain of ponds south of Kunersdorf, but it lay in full view of the artillery batteries on the Grosser Spitzberge.

[51] By 5:00 pm, neither side could make any gains; the Prussians held tenaciously to the captured artillery works, too tired to even retreat: they had pushed the Russians from the Mühlberge, the village, and the Kuhgrund, but no further.

As the hussars escorted Frederick from the battlefield, he passed the bodies of his men, lying on their faces with their backs slashed open by Laudon's cavalry.

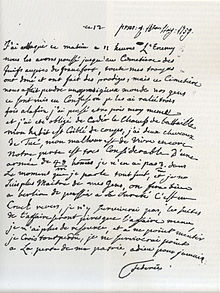

[52][56][57] That evening back in Reitwein, Frederick sat in a peasant hut and wrote a despairing letter to his old tutor, Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein: This morning at 11 o'clock I have attacked the enemy. ...

[39] In the two weeks they had to prepare for the battle, the Russians and the Austrians had discovered, and reinforced, a causeway between the lakes and the marshland that allowed them to present Frederick with a united southeastern front.

Brother Henry, a superb tactician and strategist in his own right, reasonably suggested halting the battle at mid-day, after the Prussians had secured the first height and Wunsch, the city.

[37] The Prussian cavalry effort initially drove back the Russian and Austrian squadrons, but the fierce cannon and musketry fire from the united Allied front inflicted staggering losses on Frederick's much-vaunted horsemen.

[54] Yet, as Herbert Redman notes, "... seldom in military history has a battle been so completely lost by an organized army in such a short space of time.

At Hochkirch, Frederick demonstrated good leadership by rallying his troops against the surprise attack; Prussian discipline and the bonds of regimental cohesion had prevailed.

Coloured copperplate engraving, 1793, by Peter Haas after a drawing by Bernhard Rode