Battle of Lake Khasan

[16][7] For most of the first half of the twentieth century, there was considerable tension between the Russian (later Soviet), Chinese, and Japanese governments, along their common borders in what became North East China.

In the period before the battle, a series of purges left the Soviet army with many positions filled by inexperienced officers who feared to take the initiative.

In July 1938 alone, four and a half times as many people were purged from the Far Eastern Front (the Soviet command in the region) as in the previous twelve months.

[18] In the next two weeks, small groups of Soviet border troops moved into the area and began fortifying the mountain with emplacements, observation trenches, entanglements and communication facilities.

On July 7, from Posyet where the headquarters of the 59th border detachment was located, a request was made to allow the capture of the height, which was actually already occupied: the first deputy people's commissar of internal affairs of the USSR, Mikhail Frinovsky, needed to file a document coming from his subordinates to the superior command.

On the night of July 8-9, 1938, the Soviet border guards, following the order of the command, began to install barbed wire and dig trenches.

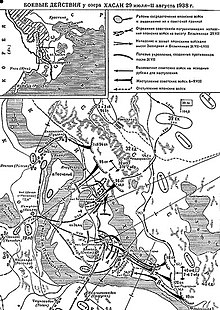

[20] The conflict started on 15 July, when the Japanese attaché in Moscow demanded the removal of Soviet border troops from the Bezymyannaya (сопка Безымянная, Chinese name: Shācǎofēng = 沙草峰) and Zaozyornaya (сопка Заозёрная, Chinese name: Zhāng Gǔfēng = 张鼓峰 (Changkufeng)) Hills to the west of Lake Khasan in the south of Primorye not far from Vladivostok, claiming this territory by the Soviet–Korea border.

Then, as follows from the documents, something completely unexpected happened: on Frinovsky’s orders, several people from his retinue crossed the border line and, entering Manchurian territory, demonstratively began to pretend to be carrying out engineering and earthworks there.

Before reaching the border, the gendarmes politely asked the Soviet comrades to stop illegal work on Manchurian territory.

Lieutenant Vinevitin, with a well-aimed rifle shot to the head, killed the persistent Japanese on the spot - on the personal order of Frinovsky.

Lieutenant General Suetaka Kamezo gave Sato an order: "You are to mete out a firm and thorough counterattack without fail, once you gather that the enemy is advancing even in the slightest".

In the Changkufeng sector, 1,114 Japanese engaged a Soviet garrison of 300, eliminating them and knocking out 10 tanks, with casualties of 34 killed and 99 wounded.

High Command rejected the request, as they knew General Suetaka would use these forces to assault vulnerable Soviet positions, escalating the incident.

The train was deployed at "2nd Armoured Train Unit" in Manchuria and participated in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Changkufeng conflict against the Soviets, transporting thousands of Japanese troops to and from the battlefield, displaying to the West the capability of an Asian nation to implement western ideas and doctrine concerning rapid infantry deployment and transport.

[citation needed] On 31 July, People's Commissar for Defence Kliment Voroshilov ordered combat readiness for 1st Coastal Army and the Pacific Fleet.

[9] Despite this, the Japanese defenders organized an anti-tank defense, with disastrous results for the poorly coordinated Soviets, whose attacks were defeated with many casualties.

[27][28] Satisfied that the incident had been brought to an "honourable" conclusion, on 11 August 1938, at 13:30 local time the Japanese stopped fighting and Soviet forces reoccupied the heights.

[32] Soviet losses totaled 792 killed or missing and 3,279 wounded or sick, according to their records and the Japanese claimed to have destroyed or immobilized 96 enemy tanks and 30 guns.

After World War II, at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1946, 13 high-ranking Japanese officials were charged with crimes against peace for their roles in initiating hostilities at Lake Khasan.