Battle of Magnesia

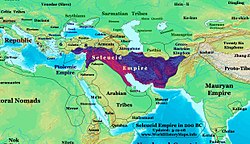

It was fought as part of the Roman–Seleucid War, pitting forces of the Roman Republic led by the consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus and the allied Kingdom of Pergamon under Eumenes II against a Seleucid army of Antiochus III the Great.

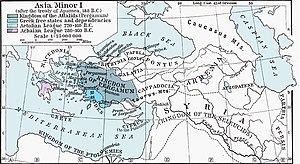

The two armies initially camped northeast of Magnesia ad Sipylum in Asia Minor (modern-day Manisa, Turkey), attempting to provoke each other into a battle on favorable terrain for several days.

The battle resulted in a decisive Roman-Pergamene victory, which led to the Treaty of Apamea that ended Seleucid domination in Asia Minor.

Fearing that Antiochus would seize the entirety of Asia Minor, the independent cities of Smyrna and Lampsacus appealed for protection from the Roman Republic.

[4] In the early spring of 196 BC, Antiochus' troops crossed to the European side of the Hellespont and began rebuilding the strategically important city of Lysimachia.

[5] In late winter 196/195 BC, Rome's erstwhile chief enemy, Carthaginian general Hannibal, fled from Carthage to Antiochus' court in Ephesus.

[6] The Aetolians began spurring the Greek states to jointly revolt under Antiochus' leadership against the Romans, hoping to provoke a war between the two parties.

The Aetolians then captured the strategically important port city of Demetrias, killing the key members of the local pro-Roman faction.

Antiochus then shifted his attention towards rebuilding his alliance with Philip V of Macedon, which had been shattered after the latter was decisively defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC.

On 26 April 191 BC, the two sides faced off at the Battle of Thermopylae, where Antiochus' army suffered a devastating defeat and he returned to Ephesus shortly afterwards.

However, the Roman fleet defeated the Seleucids in the Battle of Corycus in September 191 BC, enabling it to take control of several cities including Dardanus and Sestos on the Hellespont.

[12] Antiochus withdrew his armies from Thrace, while simultaneously offering to cover half of the Roman war expenses and accept the demands made in Lysimachia in 196 BC.

The right flank was led by Antiochus, consisting of 3,000 cataphracts, 1,000 agema cavalry, 1,000 argyraspides of the royal guard, 1,200 Dahae horse archers.

Antiochus was determined to fight his adversaries on the ground of his own choosing, and his army marched from the direction of Sardis towards Magnesia ad Sipylum, camping 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) northeast of the city.

He could not hope to win the battle by directly assaulting the heavily-fortified Seleucid camp, but by refusing to engage he risked having his supply lines cut by the numerically-superior enemy cavalry.

[26][27] On the Seleucid right flank, Antiochus led the attack with the cataphracts and agema cavalry facing the Latin infantry, while the argyraspides engaged the Roman legionaries.

The Roman infantry broke ranks retreating to their camp where they were reinforced by the Thracians and Macedonians and subsequently rallied by tribune Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.

[26][28] In the center, the Seleucid phalanx held its ground against the Roman infantry, but it was not mobile enough to dislodge the enemy archers and slingers who bombarded it with projectiles.

[27] It began a slow organized retreat, when the war elephants positioned between its taxeis panicked because of the projectiles, causing the phalanx to break formation.

The truce was signed at Sardes in January 189 BC, whereupon Antiochus agreed to abandon his claims on all lands west of the Taurus Mountains, paid a heavy war indemnity and promised to hand over Hannibal and other notable enemies of Rome from among his allies.

[34] During the summer of 189 BC, ambassadors from the Seleucid Empire, Pergamon, Rhodes, and other Asia Minor states held peace talks with the Roman Senate.

The conditions also included the requirement to hand over Hannibal, Thoantas, and twenty notables as hostages, destroy all his fleet apart from ten ships, and give Rome 40,500 modiuses of grain per year.