Battle of Monett's Ferry

Arkansas The Battle of Monett's Ferry or Monett's Bluff (April 23, 1864) saw a Confederate States Army force led by Brigadier General Hamilton P. Bee attempt to block a numerically superior Union Army column that was commanded by Brigadier General William H. Emory during the Red River Campaign of the American Civil War.

[1] The Red River campaign was undertaken because President Abraham Lincoln wanted a Union foothold in Texas to deter the French-supported ruler Maximilian I of Mexico from meddling in the war.

The aim was to establish a corridor up the Red River to Texas and Major General Henry Halleck ordered Banks to lead the operation.

Meanwhile, Major General Frederick Steele with 15,000 men moved south from Little Rock, Arkansas, planning to rendezvous with Banks near Shreveport, Louisiana.

Banks' army waited at Grand Ecore near Natchitoches until 15 April when it was rejoined by Porter's fleet, which was now returning downriver.

Banks decided to abandon the campaign because Smith's troops were already overdue to be returned to Major General William T. Sherman and because Steele was unlikely to join them.

[7] Brigadier General Camille de Polignac's infantry division moved to block a western exit from the island at Cloutierville while Brigadier General St. John Richardson Liddell's force was positioned near Colfax to block Banks' army from crossing to the east bank of the Red River.

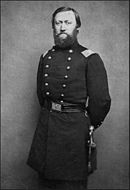

[8] After Brigadier General Thomas Green was killed at the Battle of Blair's Landing on 12 April,[9] Bee assumed command of Taylor's cavalry corps because he outranked Major who was more experienced.

[10] On the evening of 22 April, when Brigadier General John A. Wharton's Confederate cavalry tried to attack the Federal rearguard near Cloutierville, a minor panic ensued when the cavalrymen believed they were being outflanked.

[6] In the predawn hour of 23 April, Captain John M. T. Barnes'[12] 1st Louisiana Regular Battery[13] briefly shelled the Union rearguard south of Cloutierville.

[14] Brigadier General Cuvier Grover's XIX Corps division, 3,000 soldiers, had been left to garrison Alexandria during the initial Union advance.

[16] The wound Franklin received at Mansfield rendered him unfit for duty, so he handed command over to Emory on the morning of 23 April.

[4] Emory began his march at 4:30 am and advanced 3 mi (4.8 km) before his troops ran into Bee's skirmishers, which were driven across the Cane River.

Davis' mission ended in failure,[8] but Birge's troops encountered a local Black man who showed them a little-known ford about 2 mi (3.2 km) upstream.

To draw attention away from Birge's flanking column, Emory deployed the 1st and 2nd Brigades of his own division opposite the ferry crossing in a show of force.

[24] After Birge's outflanking force was detected, General Major assigned Colonel George W. Baylor to take command of the left flank.

After taking their opponents under brisk fire, Baylor's men fell back and the Union soldiers occupied the hill.

[24] While crossing another open field, Birge, his staff, and some cavalrymen rode forward to reconnoiter a wooded area in front of them.

Some Union troops were seen heading for the open flank, so Baylor ordered Madison's regiment to mount and move to the left to cover the gap.

Baylor ordered the 2nd Texas (Arizona Brigade) and Fontaine's guns to hold the ferry crossing until the left wing could escape, which was done.

Worried about Davis' abortive mission downstream and Emory's demonstration in front, as well as Birge's turning movement upstream, Bee had ordered a retreat to Beasley's Plantation.

With the crossing cleared of Confederates, Banks' African-American brigade laid a pontoon bridge across the Cane River, which was ready a little after nightfall.

Union losses during the operation numbered 300 men, including 153 from Fessenden's brigade, while Bee only admitted having lost 50 casualties.

[31] Sending Terrell's entire brigade back to Beasley's to look after a subsistence train, for the safety of which I had amply provided; second, in taking no steps to increase artificially the strength of his position; third, in massing his troops in the center, naturally the strongest part of his position and where the enemy were certain not to make any decided effort, instead of toward the lakes on which his two flanks rested; fourth, in this, that when he was forced back he retired his whole force 30 mi (48 km) to Beasley's, instead of attacking vigorously the enemy's column while marching 13 mi (21 km) to Cotile through a dense pine woods, encumbered with trains and artillery and utterly demoralized by the vigorous attacks of Wharton in the rear.

To isolate Banks at Alexandria, Taylor placed Steele with 1,000 men north and west of the city, Bagby with 1,000 soldiers on the south side, Polignac with 1,200 infantry supporting Steele and Bagby, Major with 1,000 troops at David's Ferry on the Red River below Alexandria, and Liddell with 700 on the east side of the river.