Braxton Bragg

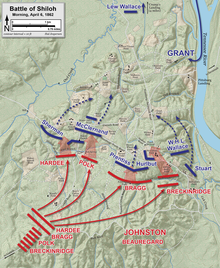

He was a corps commander at the Battle of Shiloh, where he launched several costly and unsuccessful frontal assaults but nonetheless was commended for his conduct and bravery.

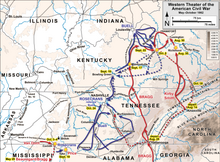

He and Brigadier General Edmund Kirby Smith attempted an invasion of Kentucky in 1862, but Bragg retreated following a minor tactical victory at the Battle of Perryville in October.

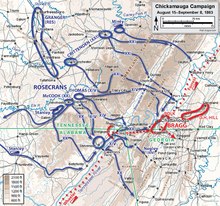

After months without significant fighting, Bragg was outmaneuvered by Rosecrans in the Tullahoma Campaign in June 1863, causing him to surrender Middle Tennessee to the Union.

Bragg was extremely unpopular with both the officers and ordinary men under his command, who criticized him for numerous perceived faults, including poor battlefield strategy, a quick temper, and overzealous discipline.

Although considered by his neighbors to be from the lower class, Thomas Bragg was a carpenter and contractor who became wealthy enough to send Braxton to the Warrenton Male Academy, one of the best schools in the state.

The series, "Notes on Our Army," published anonymously (as "A Subaltern"), included specific attacks on the policies of general in chief Winfield Scott, whom he called a "vain, petty, conniving man."

He was found guilty, but an official reprimand from the Secretary of War and suspension at half pay for two months were relatively mild punishments, and Bragg was not deterred from future criticisms of his superiors.

Bragg proposed to Davis that he change his strategy of attempting to defend every square mile of Confederate territory, recommending that his troops were of less value on the Gulf Coast than they would be farther to the north, concentrated with other forces for an attack against the Union Army in Tennessee.

Bragg transported about 10,000 men to Corinth, Mississippi, in February 1862 and was charged with improving the poor discipline of the Confederate troops already assembled under General Albert Sidney Johnston.

In the initial surprise Confederate advance, Bragg's corps was ordered to attack in a line almost 3 miles (4.8 km) long, but he soon began directing activities of the units that found themselves around the center of the battlefield.

Although Bragg was the senior general in the theater, President Davis had established Kirby Smith's Department of East Tennessee as an independent command, reporting directly to Richmond.

[30] On August 9, Smith informed Bragg that he was breaking the agreement and intended to bypass Cumberland Gap, leaving a small holding force to neutralize the Union garrison and move north.

He had to decide whether to continue toward a fight with Buell (over Louisville) or rejoin Smith, who had gained control of the center of the state by capturing Richmond and Lexington and threatened to move on Cincinnati.

Bragg replied, "I will do it, sir," but then displayed what one observer called "a perplexity and vacillation which had now become simply appalling to Smith, to Hardee, and to Polk,"[34] he ordered his army to retreat through the Cumberland Gap to Knoxville.

Disheartening news had arrived from northern Mississippi that Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price had been defeated at Corinth, just as Robert E. Lee had failed in his Maryland Campaign.

He wrote to his wife, "With the whole southwest thus in the enemy's possession, my crime would have been unpardonable had I kept my noble little army to be ice-bound in the northern clime, without tents or shoes, and obliged to forage daily for bread, etc.

"[35] He was quickly called to Richmond to explain to Jefferson Davis the charges brought by his officers about how he had conducted his campaign, demanding that he be replaced as head of the army.

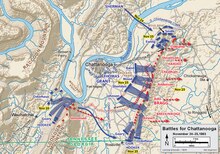

Recognizing his lack of progress, the severe winter weather, the arrival of supplies and reinforcements for Rosecrans, and heeding the recommendations of corps commanders Hardee and Polk, Bragg withdrew his army from the field to Tullahoma, Tennessee.

Bragg struck back, court-martialing one division commander (McCown) for disobeying orders, accusing another (Cheatham) of drunkenness during the battle, and blaming Breckinridge for inept leadership.

He reacted to the rumors of criticism by circulating a letter to his corps and division commanders that asked them to confirm in writing that they had recommended withdrawing after the latter battle, stating that if he had misunderstood them and withdrawn mistakenly, he would willingly step down.

While keeping Polk's corps occupied with small actions in the center of the Confederate line, Rosecrans sent the majority of his army around Bragg's right flank.

[45] A positive aspect for Bragg was Hardee's request to be transferred to Mississippi in July, but he was replaced by Lt. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill, a general who had not gotten along with Robert E. Lee in Virginia.

Thomas C. Hindman and Daniel Harvey Hill refused to attack, as ordered, an outnumbered Federal column at McLemore's Cove (the Battle of Davis's Cross Roads).

He began to wage a battle against the subordinates he resented for failing him in the campaign—Hindman for his lack of action in McLemore's Cove and Polk for delaying the morning attack Bragg ordered on September 20.

Davis was sympathetic to Bragg's discomfort and discussed transferring him to command the Trans-Mississippi Department, replacing Edmund Kirby Smith, but the politicians from that region were vehemently opposed.

[61] On his celebratory tour, Bragg visited Evergreen Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana, where he met 23-year-old Eliza Brooks Ellis, known to her friends as Elise, a wealthy sugar heiress.

Peter Cozzens wrote about his relationship with subordinates:[66] Even Bragg's staunchest supporters admonished him for his quick temper, general irritability, and tendency to wound innocent men with barbs thrown during his frequent fits of anger.

For such officers—and they were many in the Army of Mississippi—Bragg's removal or their transfer were the only alternatives to an unbearable existence.One private, Sam Watkins, who later became a professional writer, said in his memoirs that "None of Bragg's men soldiers ever loved him.

While most agree he was not a particularly good army commander, historians such as Hallock and Steven E. Woodworth cite his skills as an organizer and argue that his defeat in several battles can also be partially blamed upon bad luck and incompetent subordinates, notably Polk.

[69] Historians Grady McWhiney and Woodworth have stated that, contrary to popular belief, Davis and Bragg were not friends, having bitterly quarreled during the antebellum years.