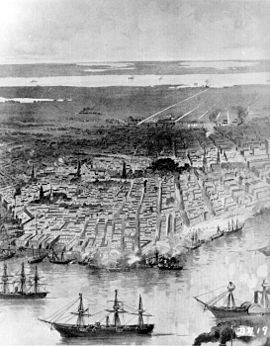

New Orleans in the American Civil War

New Orleans, Louisiana, was the largest city in the South, providing military supplies and thousands of troops for the Confederate States Army.

Its location near the mouth of the Mississippi made it a prime target for the Union, both for controlling the huge waterway and crippling the Confederacy's vital cotton exports.

In April 1862, the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Captain David Farragut shelled the two substantial forts guarding each of the river-banks, and forced a gap in the defensive boom placed between them.

The new military governor, Major General Benjamin Butler, proved effective in enforcing civic order, though his methods aroused protest everywhere.

[3] Antebellum New Orleans was the commercial heart of the Deep South, with cotton comprising fully half of the estimated $156,000,000 (in 1857 dollars) exports, followed by tobacco and sugar.

In January 1862, men from the free black community of New Orleans formed a regiment of Confederate soldiers called the Louisiana Native Guard.

Beauregard, Braxton Bragg, Albert G. Blanchard, and Harry T. Hays, the commander of the famed Louisiana Tigers infantry brigade which included a large contingent of Irish American New Orleanians.

The political and commercial importance of New Orleans, as well as its strategic position, marked it out as the objective of a Union expedition soon after the opening of the Civil War.

A formidable obstacle to the advance of the Union main fleet was a boom between the forts, designed to detain vessels under close fire if they attempted to run past.

After a severe conflict at close quarters with the forts and ironclads and fire rafts of the defense, almost all the Union fleet (except the mortar boats) forced its way past.

The ships soon steamed upriver past the Chalmette batteries, the final significant Confederate defensive works protecting New Orleans from a sea-based attack.

The Federal commander, Major General Benjamin Butler, soon subjected New Orleans to martial law that was widely reported as an affront in the Southern press.

[7] Above the general tumult, as the troops entered the streets, could be heard the loud strains of "Bonny Blue Flag," and other secession songs.

[9] As the federal troops began to appear in public, and travel about on their duties, the bitter hatred of the local white secessionists manifested in numerous ways from disgust looks to vehement verbal attacks.

[9][note 1] These wise and humane restrictions were often very galling to the pride of the men and under repeated provocation, resentment sometimes got the better of prudence, and the loyal soldiers became exasperated.

[12] Large details were made each morning to protect public and private property, to seize concealed arms, and arrest suspicious and disorderly persons.

[13] These were in a disarray and the Confederates, before evacuation, had destroyed or secreted the apparatus of the telegraph offices, cut wires, and done all they could to make the lines inoperative.

Needing a practical and capable telegrapher for the system superintendent, he asked his regimental commanders for such a man, and found the 8th Vermont's Quarter Master Sergeant J. Elliot Smith[note 2] fitting.

[16] Initially, local white citizens showed their hostility by closing stores and other public places to the federal troops, but economic necessity overrode their attitude, and they soon reopened their businesses.

Wearing small Confederate flags conspicuously on their dresses, or waving them in their hands in public places, they would rise and leave a street car if a Union officer entered it.

Among Butler's other acts cited as controversial was the June hanging of William Mumford, a pro-Confederacy man who had torn down the US flag over the New Orleans Mint, against Union orders.

Despite these, Butler's administration had benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and his massive cleanup efforts made it unusually healthy by 19th century standards.

Under Banks, relationships between the troops and citizens improved, but the scars left by the Lost Cause's depiction of Butler's administration lingered for decades.

A number of significant structures and buildings associated with the Civil War still stand in New Orleans, and vestiges of the city's defenses are evident downriver, as well as upriver at Camp Parapet.