Battle of Mons

Though initially planned as a simple tactical withdrawal and executed in good order, the British retreat from Mons lasted for two weeks and took the BEF to the outskirts of Paris before it counter-attacked in concert with the French, at the Battle of the Marne.

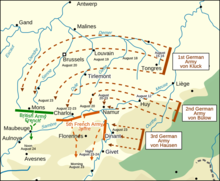

[5][6] The British position on the French flank meant that it stood in the path of the German 1st Army, the outermost wing of the massive "right hook" intended by the Schlieffen Plan (a combination of the Aufmarsch I West and Aufmarsch II West deployment plans), to pursue the Allied armies after defeating them on the frontier and force them to abandon northern France and Belgium or risk destruction.

[17] When the Germans spotted the trap and fell back, a troop of the dragoons, led by Captain Charles Hornby gave chase, followed by the rest of his squadron, all with drawn sabres.

Private E. Edward Thomas, a cavalryman and drummer, is reputed to have fired the first shot of the war for the British Army, hitting a German trooper.

[22] Late on 20 August, General Karl von Bülow, the 2nd Army commander, who had tactical control over the 1st Army while north of the Sambre, held the view that an encounter with the British was unlikely and wished to concentrate on the French units reported between Charleroi and Namur, on the south bank of the Sambre; reconnaissance in the afternoon failed to reveal the strength or intentions of the French.

Kluck wanted to advance to the south-west to maintain freedom of manuoeuvre and on 21 August, attempted to persuade Bülow to allow the 1st Army to continue its manoeuvre.

By the evening the bulk of the 1st Army had reached a line from Silly to Thoricourt, Louvignies and Mignault; the III and IV reserve corps had occupied Brussels and screened Antwerp.

More reports had reached the IX Corps, that columns were moving from Valenciennes to Mons, which made clear the British deployment but were not passed on to the 1st Army headquarters.

The two III Corps divisions were close to St. Ghislain and General Ewald von Lochow ordered them to prepare an attack from Tertre to Ghlin.

[32] At the Nimy bridge, Dease took control of his machine gun after the rest of the section had been killed or wounded and fired the weapon, despite being shot several times.

At Nimy, Private Oskar Niemeyer had swum across the canal under British fire to operate machinery closing a swing bridge.

By nightfall, II Corps had established a new defensive line running through the villages of Montrœul, Boussu, Wasmes, Paturages and Frameries.

[42] Sir John finally accepted that an advance would not be able to take place and admitted that a retreat had to be made quickly, else the consequences would be irreparable for the BEF.

[43] The unexpected order to retreat from prepared defensive lines in the face of the enemy, meant that II Corps was required to fight a number of sharp rearguard actions against the Germans.

Their refusal to fall back without orders led Smith-Dorrien to later state that on reflection the 1st Battalion, Cheshires together with the Duke of Wellington's regiment had "saved the BEF".

[46] On the extreme left of the British line, the 14th and 15th brigades of the 5th Division were threatened by a German outflanking move and were forced to call for help from the cavalry.

[49] By 11:00 a.m., reports from the IV, III and IX corps revealed that the British were in St. Ghislain and at the canal crossings to the west, as far as the bridge at Pommeroeuil, with no troops east of Condé.

In the early afternoon, the II Cavalry Corps reported that it had occupied the area of Thielt–Kortryk–Tournai during the night and forced back a French brigade to the south-east of Roubaix.

On the left flank, the division advanced towards a bridge north-east of Wasmuel and eventually managed to get across the canal against determined resistance, before turning towards St. Ghislain and Hornu.

As dark fell, Wasmuel was occupied and attacks on St. Ghislain were repulsed by machine-gun fire, which prevented troops crossing the canal except at Tertre, where the advance was stopped for the night.

The British in the village stopped the division with small-arms fire, except for small parties, who found cover west of a path from Ghlin to Jemappes.

The III and IX corps' attack during the day, had succeeded against "a tough, nearly invisible enemy" but the offensive had to continue, because it appeared that only the right flank of the army could get behind the BEF.

At 4:00 p.m. cavalry reports led Quast to resume the advance, which was slowed by the obstacles of Maubeuge and III Corps congesting the roads.

St. Ghislain had been attacked by the 5th Division behind an artillery barrage, where the 10th Brigade had crossed the canal and taken the village in house-to-house fighting, then reached the south end of Hornu.

[57] The chaos and confusion were graphically illustrated in Landrecies on 25 August, where a senior officer "apparently took leave of his senses and began firing his revolver down a street".

German novelist and infantry officer Walter Bloem wrote: The men all chilled to the bone, almost too exhausted to move and with the depressing consciousness of defeat weighing heavily upon them.

It was believed that only part of the BEF had been engaged and that there was a main line of defence from Valenciennes to Bavay, which Kluck ordered to be enveloped on 25 August.

[71] Mons gained two myths, the first being the a miraculous tale that the Angels of Mons—angelic warriors sometimes described as phantom longbowmen from Agincourt—had saved the British Army by halting the German troops.

According to the controversial book Falsehood in War-Time, an investigation conducted by General Frederick Maurice traced the origins of the Order to the British GHQ, where it had been concocted for propaganda purposes.

More British, Canadian and German graves were moved to the cemetery from other burial grounds and more than 500 soldiers were eventually buried in St. Symphorien, of which over 60 were unidentified.