Battle of Oivi–Gorari

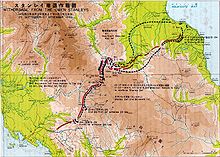

Over the course of several days, determined resistance held off a number of frontal assaults, forcing the commander of the 7th Division, Major General George Vasey, to attempt a flanking move from the south.

Hand-to-hand fighting resulted in heavy casualties on both sides before the Japanese withdrew east and crossed the flood-swollen Kumusi River, where many drowned and a large quantity of artillery had to be abandoned.

On 21 July 1942, Japanese forces landed on the northern Papuan coast around Buna and Gona, as part of a plan to capture the strategically important town of Port Moresby via an overland advance along the Kokoda Track following the failure of a seaborne assault during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May.

Following reverses around Milne Bay and Guadalcanal,[2] and a climactic battle around Ioribaiwa, in early September the Japanese reached the limits of their supply line and were ordered to assume a defensive posture until conditions became more favourable for a renewed effort on Port Moresby.

[12] The forward airfield also greatly reduced the time taken to evacuate casualties to Port Moresby, significantly improving a wounded soldier's chances of survival.

Nevertheless, the Australians pushed forward along the narrower north–south track that ran between Kokoda and Sanananda,[13] until they were halted along the high ground around Oivi by a strongly entrenched Japanese force.

[22] As the pincer movement threatened to encircle the Japanese defenders around Oivi who were running low on ammunition and who were weak from lack of food, Horii gave the order for them to withdraw.

The Australians reached the Kumusi River, around Wairopi on 13 November,[23] where the Japanese were forced to abandon much of their artillery and a large amount of ammunition and other stores,[13] effectively drawing the Kokoda Track campaign to a close.

[27] The months that followed saw heavy fighting on the northern coast of Papua, around Buna and Gona, as the Allies undertook a costly frontal assault against the Japanese beachheads, which had been heavily fortified.

[13] Additionally, the resultant need to cross the river – which was up to 100 metres (330 ft) wide in some places – as the Japanese withdrew further had the added effect of causing more losses due to drowning, with Horii himself becoming a victim of this fate as he attempted to raft and then canoe towards Giruawa.

[30][31] In analysing the battle, author Peter Brune later wrote that Horii had erred in choosing to mount a stand around Gorari, with the ground beyond the Kumusi seemingly offering better defensive characteristics.