Battle of Passchendaele

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), did not receive approval for the Flanders operation from the War Cabinet until 25 July.

Remaining controversial are the choice of Flanders, its climate, the selection of General Hubert Gough and the Fifth Army to conduct the offensive, and debates over the nature of the opening attack and between advocates of shallow and deeper objectives.

[4] In December, the British Admiralty began discussions with the War Office, for a combined operation to re-occupy the Belgian coast but were obliged to conform to French strategy and participate in offensives further south.

[8] A week after his appointment, Haig met Rear-Admiral Reginald Bacon, who emphasised the importance of obtaining control of the Belgian coast, to end the threat posed by German U-boats.

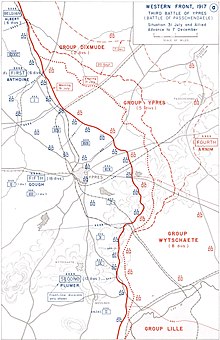

[9] In January 1917, the Second Army (General Herbert Plumer) with the II Anzac, IX, X and VIII corps, held the Western Front in Flanders from Laventie to Boesinghe, with eleven divisions and up to two in reserve.

[14] The plan for a year of attrition offensives on the Western Front, with the main effort to be made in the summer by the BEF, was scrapped by the new French Commander-in-Chief Robert Nivelle in favour of a return to a strategy of decisive battle.

[22] Haig wished to exploit the diversion of German forces in Russia for as long as it continued and urged the British War Cabinet to commit the maximum amount of manpower and munitions to the battle in Flanders.

The lowland west of the ridge was a mixture of meadows and fields, with high hedgerows dotted with trees, cut by streams and a network of drainage ditches emptying into canals.

On 30 June, the army group Chief of Staff, General von Kuhl, suggested a withdrawal to the Flandern I Stellung along Passchendaele ridge, meeting the old front line in the north near Langemarck and Armentières in the south.

Loßberg disagreed, believing that the British would launch a broad front offensive, that the ground east of the Sehnenstellung was easy to defend and that the Menin road ridge could be held if it was made the Schwerpunkt (point of main effort) of the German defensive system.

[47] The attack was not planned as a breakthrough operation and Flandern I Stellung, the fourth German defensive position, lay 10,000–12,000 yd (5.7–6.8 mi; 9.1–11.0 km) behind the front line and was not an objective on the first day.

[48] Major-General John Davidson, Director of Operations at GHQ, wrote in a memorandum that there was "ambiguity as to what was meant by a step-by-step attack with limited objectives" and suggested reverting to a 1,750 yd (1,600 m) advance on the first day to increase the concentration of British artillery.

[56] Hermann von Kuhl, chief of staff of Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht, wrote later that it was a costly defeat and wrecked the plan for relieving fought-out (exhausted) divisions in Flanders.

[60] On the higher ground, the Germans continued to inflict many losses on the British divisions beyond Langemarck but on 19 August, after two fine dry days, XVIII Corps conducted a novel infantry, tank, aircraft and artillery operation.

[65] In Field Marshal Earl Haig (1929), Brigadier-General John Charteris, the BEF Chief of Intelligence from 1915 to 1918, wrote that Careful investigation of records of more than eighty years showed that in Flanders the weather broke early each August with the regularity of the Indian monsoon: once the Autumn rains set in difficulties would be greatly enhanced....Unfortunately, there now set in the wettest August for thirty years.only the first part of which was quoted by Lloyd George (1934), Liddell Hart (1934) and Leon Wolff (1959); in a 1997 essay, John Hussey called the passage by Charteris "baffling".

[84] Ludendorff ordered the Stellungsdivisionen (ground holding divisions) to reinforce their front garrisons; all machine-guns, including those of the support and reserve battalions were sent into the forward zone, to form a cordon of four to eight guns every 250 yd (230 m).

[90] Aircraft were to be used for systematic air observation of German troop movements, to avoid the failures of previous battles, where too few aircrews had been burdened with too many duties and had flown in bad weather, which made their difficulties worse.

The 5th Australian Division advance the next day began with uncertainty as to the security of its right flank; the attack of the depleted 98th Brigade was delayed and only managed to reach Black Watch Corner, 1,000 yd (910 m) short of its objectives.

[103] Unternehmen Hohensturm (Operation High Storm) was planned by Gruppe Ypern to recapture the Tokio Spur from Zonnebeke south to Molenaarelsthoek at the eastern edge of Polygon Wood on 3 October.

[108] The British attacked along a 14,000 yd (8.0 mi; 13 km) front and as the I Anzac Corps divisions began their advance towards Broodseinde Ridge, men were seen rising from shell-holes in no man's land and more German troops were found concealed in shell-craters.

Without the divisions necessary for a counter-offensive south of the Gheluvelt Plateau towards Kemmel Hill, Rupprecht began to plan for a slow withdrawal from the Ypres Salient, even at the risk of uncovering German positions further north and on the Belgian coast.

The offensive was to continue, to reach a suitable line for the winter and to keep German attention on Flanders, with a French attack due on 23 October and the Third Army operation south of Arras scheduled for mid-November.

[122] On 18 October, Kuhl advocated a retreat as far to the east as possible; Sixt von Armin and Loßberg wanted to hold on, because the ground beyond the Passchendaele watershed was untenable, even in winter.

[124] After numerous requests from Haig, Petain began the Battle of La Malmaison, a long-delayed French attack on the Chemin des Dames, by the Sixth Army (General Paul Maistre).

The area was subjected to constant German artillery bombardments and its vulnerability to attack led to a suggestion by Brigadier C. F. Aspinall, that either the British should retire to the west side of the Gheluvelt Plateau or advance to broaden the salient towards Westroosebeke.

[138] A decade later, Jack Sheldon wrote that relative casualty figures were irrelevant, because the German army could not afford the losses or to lose the initiative by being compelled to fight another defensive battle on ground of the Allies' choosing.

By blaming an individual, the rest of the German commanders were exculpated, which gave a false impression that OHL operated in a rational manner, when Ludendorff imposed another defensive scheme on 7 October.

[141] The experience of the failure to contain the British attacks at Ypres and the drastic reduction in areas of the western front that could be considered "quiet" after the tank and artillery surprise at Cambrai, left the OHL with little choice but to return to a strategy of decisive victory in 1918.

[150] In 2007, Jack Sheldon wrote that although German casualties from 1 June to 10 November were 217,194, a figure available in Volume III of the Sanitätsbericht (Medical Report, 1934), Edmonds may not have included these data as they did not fit his case, using the phrases "creative accounting" and "cavalier handling of the facts".

[163] The 4th Army diary recorded that the withdrawal was discovered at 4:40 a.m. Next day, at the Battle of Merckem, the Germans attacked from Houthulst Forest, north-east of Ypres and captured Kippe but were forced out by Belgian counter-attacks, supported by the II Corps artillery.